You’re staring at a tire gauge, a coffee machine boiler, or maybe a scuba tank, and the numbers just don't look right. One says bar. The other says psi. You know they're related, but honestly, "kinda close" isn't good enough when you're dealing with pressurized systems. Pressure is one of those things we take for granted until a pipe bursts or a tire wears unevenly.

So, let's get the math out of the way immediately. 1 bar equals 14.5038 psi.

Most people just round it to 14.5 and call it a day. That works for your mountain bike tires, but if you’re calibrating industrial sensors or working on a high-end espresso shot, those extra decimals actually start to matter. It's a weird quirk of history that we're stuck between these two systems, and understanding the "why" helps you remember the "how."

The Messy Reality of 1 bar to psi

We live in a world divided by units. Most of the globe uses the metric system, where the bar is the king of atmospheric pressure. It’s neat. It’s based on the megapascal (MPa) and fits perfectly into the International System of Units. Then you have the US and a few other spots using psi, or pounds per square inch.

It’s literally a measure of weight—one pound of force—smashed onto a single square inch of surface area.

Imagine a little square, one inch by one inch. Now imagine a pound of butter sitting on it. That’s 1 psi. Now stack 14 and a half blocks of butter on that same tiny square. That’s 1 bar to psi. It sounds like a lot of butter, and in terms of physical force, it is.

Why 1 Bar Isn't Exactly One Atmosphere

Here is where it gets annoying. Many people think 1 bar is the pressure of the air at sea level. It isn't. Not exactly.

Standard atmospheric pressure (1 atm) is actually $1.01325\text{ bar}$ or $14.696\text{ psi}$. This means if you calibrate your gear to exactly 1 bar, you're actually slightly below the weight of the air pressing down on you right now. For a diver, this is the difference between a safe ascent and a headache. For a mechanic, it's the difference between a perfectly seated bead on a tubeless tire and a slow leak.

Where These Numbers Actually Hit the Real World

Let's talk about coffee. If you're a home barista, you’ve probably seen "9 bar" touted as the gold standard for espresso. Why 9? Because 9 bar is roughly 130 psi. That is the specific amount of force required to push hot water through a compacted puck of coffee grounds to emulsify oils into that beautiful crema. If your machine only hits 1 bar, you aren't making espresso; you're making very slow, very sad drip coffee.

In the world of automotive maintenance, the 1 bar to psi conversion is a daily ritual.

Most passenger car tires want about 32 to 35 psi. If you're using a European air pump marked in bar, you’re looking for roughly 2.2 to 2.4 bar. Overfilling by even 0.2 bar might not seem like much, but that’s nearly 3 psi. That’s enough to make your ride feel like you're driving on wooden wheels and to wear out the center of your tread prematurely.

The Physics of the "Bar"

The term "bar" comes from the Greek word baros, meaning weight. It was introduced by the Norwegian meteorologist Vilhelm Bjerknes. He wanted something that made sense for weather reporting. Since then, it’s become the shorthand for high-pressure systems.

Technically, $1\text{ bar} = 100,000\text{ pascals}$.

Pascals are the "official" unit, named after Blaise Pascal, but they are tiny. One pascal is roughly the pressure of a single sheet of paper resting on a table. Nobody wants to say their car tire is at 220,000 pascals. It's clunky. So we use bar. Or psi.

Converting on the Fly (The Cheat Sheet)

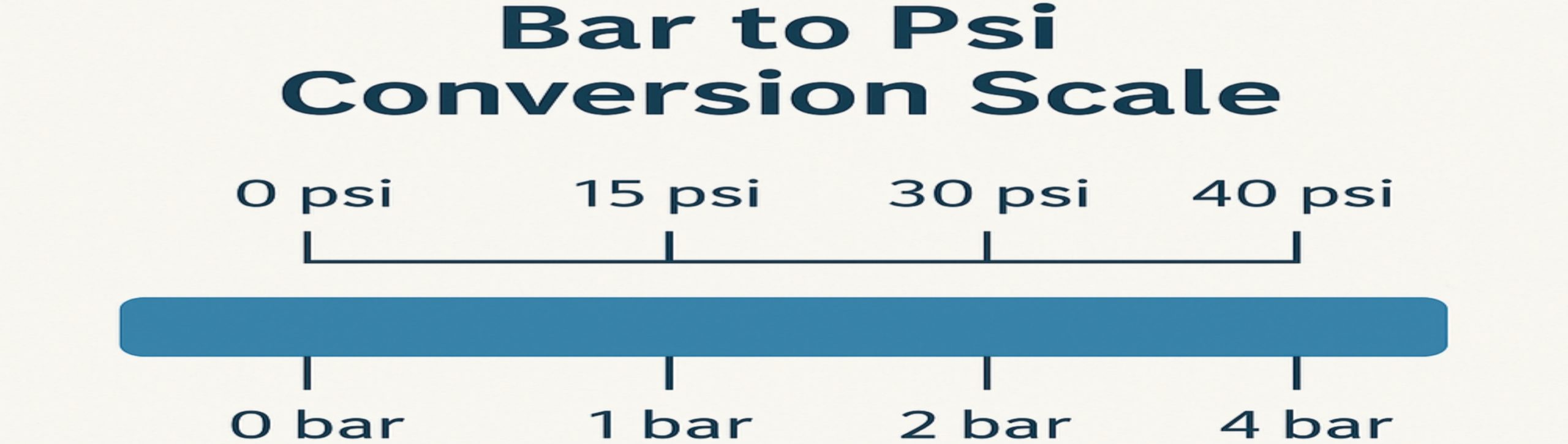

If you don't have a calculator or a phone handy, you need a way to do this in your head.

- To go from bar to psi: Multiply by 15, then subtract a little bit.

- To go from psi to bar: Divide by 15. It won't be perfect, but it'll get you in the ballpark.

For example, if you see 4 bar, $4 \times 15 = 60$. The real answer is 58.01. You’re off by 2, which is usually fine for a garden hose but bad for a turbocharger.

When Precision is Non-Negotiable

In HVAC systems or scuba diving, "close enough" is dangerous. Scuba tanks are often filled to 200 or 300 bar.

- 200 bar is roughly 2,900 psi. * 300 bar is roughly 4,350 psi.

If a technician confuses these or rounds incorrectly, they could over-pressurize a cylinder beyond its hydrostatic test rating. Metal fatigue isn't something you want to mess with at 60 feet underwater.

💡 You might also like: Energy chain for flashlight: Why your light dies when you need it most

Common Misconceptions About Pressure Units

A huge mistake people make is confusing "Bar" with "Bara" or "Barg."

Barg (Bar Gauge) measures pressure relative to the ambient atmosphere. Most gauges you'll ever touch are "gauge" units. They read zero when they're just sitting on the shelf, even though the weight of the world's air is actually pressing on them.

Bara (Bar Absolute) includes that atmospheric pressure.

So, if your gauge says 1 bar (gauge), the absolute pressure is actually about 2 bar. If you’re buying parts or sensors online, especially from industrial suppliers like Grainger or McMaster-Carr, you have to know which one you’re looking at. Buying a 1-bar-absolute sensor when you need a 1-bar-gauge sensor will result in readings that are off by roughly 14.5 psi right out of the box.

The Problem With "Pounds"

The term "psi" is actually a bit lazy. It should be "psig" or "psia," but we’ve dropped the extra letters in common parlance. This leads to massive confusion in engineering. In the 1990s, NASA lost the Mars Climate Orbiter because one team used metric units and the other used English units. While that was Newton-seconds vs. pound-seconds, the principle remains: units kill machines.

Technical Nuance: The Temperature Factor

Pressure doesn't exist in a vacuum (pun intended). If you have 1 bar of air in a sealed container and you heat it up, the psi will climb even though you didn't add more air. This is the Gay-Lussac's Law.

Basically: $P_1/T_1 = P_2/T_2$.

📖 Related: How to Hack ChatGPT: What the Jailbreak Community Actually Discovered

If you check your tires in a heated garage (let's say 20°C) and then drive out into a -10°C winter morning, your 1 bar of pressure will drop significantly. You might lose 2 or 3 psi just from the cold. This is why your "low tire pressure" light always comes on during the first cold snap of November. The air didn't leak out; it just got "smaller."

Actionable Steps for Managing Pressure Conversions

Stop guessing. If you work with tools, engines, or coffee, you need a strategy.

- Buy a Dual-Scale Gauge: If you're tired of doing the math, just replace your analog gauges with ones that show both bar and psi on the face. They cost the same and save you the mental gymnastics.

- The "14.5" Rule: Memorize this number. It is the bridge between the two worlds. Write it on a piece of masking tape and stick it to your air compressor.

- Check Your "Zero": Always make sure your gauge returns to zero when disconnected. If a bar gauge is reading 0.1 bar while sitting on the bench, it’s already lying to you by 1.5 psi.

- Use Digital for High Stakes: For anything over 10 bar, stop using analog needles. Parallax error (looking at the needle from an angle) can make you misread the gauge by several psi. Digital manometers eliminate that human error.

Pressure is literally the energy stored in a fluid or gas. Whether you're dealing with 1 bar to psi for a DIY project or a professional application, respect the decimal points. A little bit of rounding error might not seem like a big deal, but across a large surface area, that "little bit" of force adds up to hundreds of pounds of unintended pressure.

Understand the limit of your equipment. Most home-grade hoses are rated for about 10 bar (145 psi). Pushing them to 11 bar might seem fine, but you're flirting with the burst pressure. Stay within the specs, keep your conversion factor at 14.5038, and you'll avoid the literal and figurative blowups that come from unit errors.