You’d think it’d be simple. Pick up a cube, look at it, and tell me how many flat sides it has. Most people get that right—it’s six. But things get weirdly complicated the moment you move away from basic blocks and start looking at the geometry that powers everything from your favorite video game characters to the architectural marvels in Dubai. Understanding 3D shapes and faces isn't just a third-grade math requirement; it is the fundamental language of the physical and digital world. Honestly, if you don't get the relationship between a face, an edge, and a vertex, you’re going to have a hard time grasping how a computer renders a realistic human face or why certain bridges don't fall down.

Geometry is tactile.

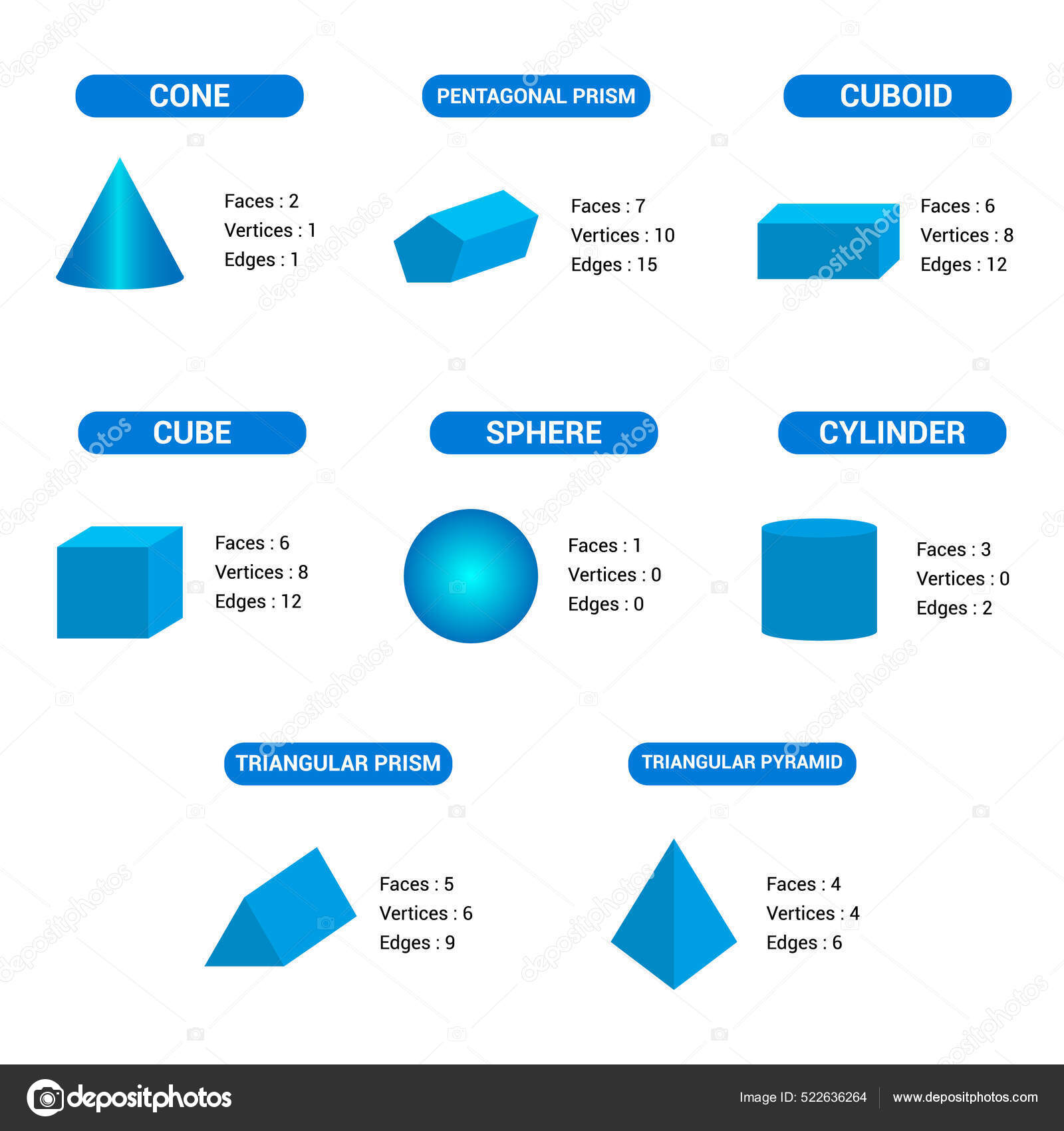

When we talk about a "face" in geometry, we are talking about the individual flat surfaces that make up a three-dimensional object. If it’s curved, like a sphere, some mathematicians get into heated debates about whether it actually has a "face" at all. Most educational standards, like the Common Core or the UK's National Curriculum, define a face as a flat surface. This means a cylinder has two faces (the circles on top and bottom) and one curved surface. A sphere? Zero faces. But wait—if you ask a topologist or a CAD designer using B-rep (Boundary Representation) modeling, they might tell you something totally different. They see surfaces as entities, regardless of their curvature. It’s this nuance that makes the study of polyhedra so much more than just counting sides on a die.

The Euler Characteristic and the Secret Math of 3D Shapes and Faces

There is a guy you should know about: Leonhard Euler. Back in the 18th century, he noticed something crazy about 3D shapes. He realized that for any convex polyhedron—think of these as "solid" shapes with flat faces and straight edges—there is a constant relationship between the number of faces ($F$), the vertices ($V$), and the edges ($E$). He wrote it down as a formula that looks like this: $V - E + F = 2$.

It's called Euler's Formula.

Try it with a cube. A cube has 8 vertices (corners), 12 edges, and 6 faces. So, $8 - 12 + 6$. That equals 2. It works every single time for these types of shapes. It works for a tetrahedron (4 faces, 4 vertices, 6 edges). It works for a dodecahedron. Why does this matter? Because it allows engineers and computer scientists to verify if a 3D model is "manifold." In layman's terms, "manifold" means the shape is watertight. If the math doesn't equal 2, there’s a hole in your digital bucket. This is how 3D printing software knows your design is broken before you even hit "print."

But math isn't just about perfect cubes.

Consider the "Great Stella" software or the work of Father Magnus Wenninger, a monk who spent his life making paper models of complex, "star-shaped" polyhedra. When you start looking at non-convex shapes—shapes that have "dents" or intersections—Euler’s rule starts to behave differently. This is where the 3D shapes and faces conversation gets genuinely interesting. You start moving into the territory of the Poincare Conjecture and higher-dimensional topology. Basically, geometry isn't just about what you see; it's about how the parts are knitted together.

Why Cones and Cylinders Create Arguments

If you want to start a fight in a room full of math teachers, ask them how many faces a cone has. One? Two? Some say the circle at the bottom is the only face because a face must be flat. Others argue the "slanted" side is a face, just a curved one.

👉 See also: Show Me Front Door: The Real Reason Your Smart Home Isn't Listening

In most K-12 classrooms, we stick to the "flat surfaces only" rule. Under that rule, a cone has one face and one curved surface. A cylinder has two faces and one curved surface. But move into the world of industrial design or 3D animation software like Blender or Autodesk Maya. To these programs, everything is a "face." In fact, in 3D modeling, curved surfaces don't even really exist. They are just thousands of tiny, flat, triangular or quadrilateral faces stitched together to look smooth. This is called a "polygon mesh." When you see a high-res character in a movie, you aren't looking at a curve; you’re looking at millions of tiny 3D shapes and faces tricking your eyes into seeing smoothness.

Real-World Geometry: It’s All About the Triangles

Ever wonder why everything in computer graphics is made of triangles? Why not squares or hexagons?

Triangles are the simplest possible polygon. They are always "planar." This means that no matter where you move the three points (vertices) of a triangle, the face between them will always be flat. If you have a four-sided shape (a quad) and you move one corner slightly too far, the face can "bend" or "warp." Computers hate that. Warped faces make lighting look weird and shadows look glitchy.

- Triangles are mathematically stable.

- They are the "atoms" of the 3D world.

- Every complex 3D shape can be broken down into triangles.

Look at the Louvre Pyramid in Paris. Designed by I.M. Pei, it’s a massive 3D shape—a square-based pyramid. It has 5 faces: the square base and four triangular sides. Except, it’s actually made of many smaller panes of glass. By using triangles and rhombs, Pei ensured the structure remained stable and visually striking. This is geometry leaping off the graph paper and into the skyline.

✨ Don't miss: The Schedule 1 Stealthy Anti Gravity Athletic Movement: Why It’s Shaking Up High-Performance Sport

Navigating the Language of Polyhedra

We use specific names for these things for a reason. "Poly" means many, and "hedron" means face. So a polyhedron is literally a "many-faced" solid.

- Tetrahedron: 4 faces (all triangles). It’s the simplest 3D shape with flat faces.

- Hexahedron: 6 faces. You know this as a cube.

- Octahedron: 8 faces. Think of two pyramids glued together at the base.

- Dodecahedron: 12 faces. Usually pentagons.

- Icosahedron: 20 faces. The classic "D20" die from Dungeons & Dragons.

The Platonic Solids are a special group where every face is the exact same regular polygon, and the same number of faces meet at every corner. There are only five of them. Plato, the Greek philosopher, thought these shapes were the building blocks of the universe. He associated the cube with earth, the tetrahedron with fire, and the icosahedron with water. He was wrong about the physics, but he was right about the elegance. These shapes are perfectly balanced.

The Geometry of Modern Tech

Let’s talk about 3D printing. When you save a file for a 3D printer, you usually save it as an .STL file. STL stands for Stereolithography. This file format basically ignores the "solid" part of the object and only records the "tessellation"—the skin of the object made of countless triangles.

If the faces aren't closed properly, the printer gets confused. It doesn't know what is "inside" and what is "outside." This is known as a "non-manifold" error. It’s a common headache for hobbyists. If two faces share an edge but aren't properly connected in the code, the printer might try to print a wall with zero thickness. It fails. Every time. Understanding how 3D shapes and faces connect at the edge level is the difference between a successful print and a "spaghetti" mess of wasted plastic on the printer bed.

The same applies to GPS and mapping. The Earth is a "geoid," sort of a lumpy sphere. To map it, we use a coordinate system that treats the Earth as a collection of geometric surfaces. Even the way we calculate the shortest distance between two points on the globe (a Great Circle route) depends on understanding the geometry of a curved surface.

Actionable Steps for Mastering 3D Concepts

If you’re trying to teach this to someone, or you’re trying to level up your own spatial reasoning, don't just look at pictures. Pictures are 2D representations of 3D objects, which is exactly why they are confusing.

Get hands-on with a "Net"

A net is a 2D pattern that you can fold to make a 3D shape. It’s the best way to see how faces relate to edges. If you unfold a cereal box, you’ve just created a net of a rectangular prism. You can clearly see the 6 faces laid out flat.

Use the "Slice" Method

Imagine taking a laser and slicing through a shape. What 2D shape do you see on the "cut" surface? This is called a cross-section. If you slice a cube diagonally, you can actually get a hexagonal cross-section. It’s mind-blowing the first time you see it.

Count the Vertices First

When you’re stuck trying to identify a complex shape, don’t start with the faces. Start with the corners (vertices). Then count the edges. Finally, use Euler’s $V - E + F = 2$ formula to figure out how many faces should be there. It’s a great way to double-check your work.

Play with Digital Tools

Download a free tool like Tinkercad or Blender. Even just moving a cube around in a 3D space teaches you more about faces and perspective than any textbook. Watch how a face disappears when it turns away from your "camera" view. That’s "backface culling," a trick computers use to save processing power by not drawing the faces you can't see.

Geometry isn't a dead subject. It’s evolving. From the way we design carbon nanotubes in medicine to the way we map the universe, the study of 3D shapes and faces remains our primary tool for making sense of space. Next time you see a soccer ball (a truncated icosahedron!), take a second to count the pentagons and hexagons. You’ll see the math holding it all together.