You’re holding a dice. Or maybe a soda can. Or you're looking at the weirdly satisfying angles of a Pyraminx. Most people don't think about it, but the world is basically just a messy collection of 3d shapes with faces, edges, and vertices. It sounds like something you left behind in fourth grade, right? Honestly, though, the way we understand these shapes is the literal foundation of everything from the CGI in the latest Pixar flick to the structural integrity of the bridge you drove over this morning.

Geometry is tactile.

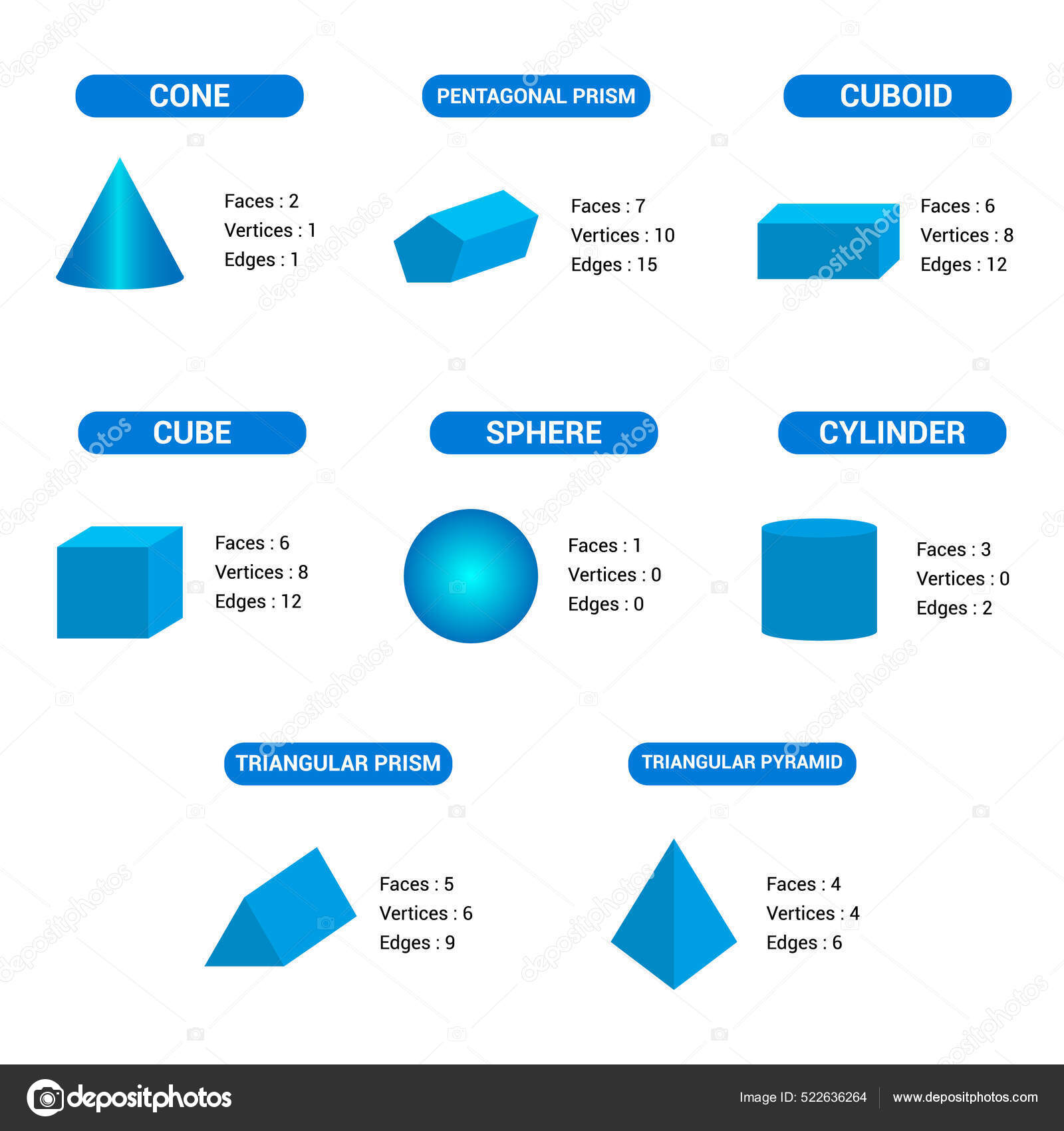

If you can’t touch it, you can’t build it. When we talk about 3d shapes with faces, we're diving into polyhedra—solids with flat surfaces. But here’s the kicker: not everything that's "3D" follows the same rules. A sphere is a 3D shape, sure, but it has no flat faces. It’s just one continuous, curved surface. To a topologist, that’s a whole different ball game. To a builder or a coder, the "face" of the shape is where the magic happens. It’s the interface. It’s the boundary.

The Flat Truth About Polyhedra

Let’s get the basics out of the way before we get into the weird stuff. A face is a flat surface. If it’s curved, most mathematicians—like those at the Mathematical Association of America—won't call it a face in the strict "polyhedral" sense. They call it a surface.

Think about a cube. Everyone knows a cube. It has six faces. They’re all squares. Simple.

But then you look at something like a dodecahedron. It has 12 pentagonal faces. It looks like something out of a sci-fi movie, but it's actually one of the five Platonic solids. These are the "perfect" shapes where every face is an identical regular polygon, and the same number of faces meet at every corner. Plato thought these shapes represented the elements of the universe—fire, earth, air, water, and the cosmos. Kind of a lot of pressure for a bunch of triangles and squares, right?

The five Platonic solids are:

💡 You might also like: How Long Does It Take for Fossil Fuels to Form: The Millions of Years Most People Get Wrong

- The Tetrahedron: 4 triangular faces. It’s a pyramid, basically.

- The Hexahedron (Cube): 6 square faces.

- The Octahedron: 8 triangular faces. Imagine two pyramids glued together at the base.

- The Dodecahedron: 12 pentagonal faces.

- The Icosahedron: 20 triangular faces. This is your classic D20 for the D&D fans.

Euler’s Formula: The Cheat Code

There’s this guy, Leonhard Euler. Absolute legend in the math world. Back in the 1700s, he figured out a relationship that works for almost any "convex" polyhedron. It’s a bit of a mind-bender because it always stays the same, no matter how many faces you add.

The formula is $V - E + F = 2$.

$V$ is vertices (corners). $E$ is edges. $F$ is faces.

Take a cube. It has 8 vertices and 12 edges. So, $8 - 12 + F = 2$. Do the math, and $F$ has to be 6. It’s like a universal law that keeps the universe from falling apart. If you try to build a shape that doesn't fit this rule, it’s probably going to have a hole in it or be "non-convex," which is a whole other headache for structural engineers.

Why 3D Shapes With Faces Drive Modern Tech

You might think this is just abstract fluff. It's not.

Every single video game you play is built on "polys." When developers talk about "low-poly" or "high-poly" models, they are literally talking about the number of 3d shapes with faces used to create a character. Lara Croft in the 90s was made of maybe 500 triangles. Today’s characters use millions.

Why triangles?

Because they are the simplest possible polygon. Three points always define a flat plane. You can't bend a triangle. If you have four points (a quadrilateral), one of those points could wiggle out of alignment, and suddenly your face isn't flat anymore. It warps. For a computer trying to calculate how light hits a surface, a warped face is a nightmare. Triangles keep it simple. They keep the math predictable.

In architectural software like AutoCAD or Revit, understanding how faces join is the difference between a roof that holds up and one that collapses under snow. Architects use "tessellation"—fitting shapes together with no gaps—to create those crazy glass facades you see on modern skyscrapers. Those are just thousands of 3d shapes with faces working in unison.

The Misconception of the Cylinder

People argue about this all the time. Does a cylinder have faces?

If you ask a primary school teacher, they'll say yes: it has two circular faces and one curved surface. But if you're talking to a pure geometer, they might get prickly. In the world of polyhedra, a "face" must be a polygon. A circle isn't a polygon because it doesn't have straight sides.

So, technically, a cylinder is a "curved solid," not a polyhedron.

It’s the same deal with cones. One flat(ish) circular base and one curved surface that comes to a point (the apex). If we're being honest, the terminology depends on who you're talking to. In a practical engineering sense, we call them faces because we need to measure their area. If you’re painting a water tank, you need to know the surface area of the "faces," regardless of whether they’re flat or round.

Surprising Shapes You’ve Never Heard Of

Beyond the cubes and pyramids lies a world of "Archimedean solids." These are shapes that have more than one type of polygon for their faces.

🔗 Read more: Theory of Numbers: Why the Simplest Math is Actually the Hardest

Take the Truncated Icosahedron.

That’s a fancy name for a soccer ball. It has 32 faces in total: 12 pentagons and 20 hexagons. It’s one of the most stable structures in nature. In fact, chemists discovered a carbon molecule shaped exactly like this, called Buckminsterfullerene (or "Buckyballs"). It turns out nature is pretty obsessed with 3d shapes with faces because they offer the most strength for the least amount of material.

Then you have things like the "Great Stellated Dodecahedron." It looks like a spiked star from a Mario game. It’s beautiful, complex, and a total nightmare to calculate the surface area for. These are non-convex, meaning they have indentations and points that stick out, breaking Euler's simple rule.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you're a hobbyist, a student, or just someone trying to understand why your IKEA furniture looks the way it does, there are a few practical takeaways.

First, volume and surface area are everything. For any 3D shape, the "faces" determine how much material you need to cover it, while the space inside is the volume.

Pro-tip for DIYers: If you’re building a shed or a box, always calculate for "waste." When you're cutting flat sheets of wood to create the faces of a 3D object, you will never use 100% of the material. There’s always an edge you lose.

For the digital artists: Topology matters more than the face count. "Good" topology means your faces are organized in a way that allows the shape to deform (like a character’s face moving when they talk) without looking like a crumpled soda can.

For the curious: Next time you’re outside, look for the "hexagons" in nature. You'll see them in beehives, on the back of a tortoise shell, and even in the basalt columns of the Giant's Causeway. Nature loves a hexagon because it’s the most efficient way to divide a surface into faces with the shortest total perimeter.

Moving Forward With 3D Geometry

Don't let the jargon intimidate you. At its core, studying 3d shapes with faces is just about spatial reasoning. It’s about seeing the world not as a flat image, but as a collection of surfaces meeting at angles.

If you want to get better at visualizing this, start by deconstructing things. Grab a cereal box and cut it along the edges until it lays flat. That flat layout is called a "net." Every 3D shape with flat faces has a net. Seeing how a 2D sheet of cardboard transforms into a 3D prism is the "Aha!" moment most people need to finally get geometry.

Go find a complex object in your house—maybe a lamp or a kitchen appliance. Try to identify every single face. Is it flat? Is it curved? How many edges meet at the corners? Once you start seeing the faces, you can't un-see them. The world becomes a lot more structured, and honestly, a lot more interesting.

The next step is to grab some graph paper and try drawing a net for a shape you've never seen before. Try a hexagonal prism or a square-based pyramid. Fold it up. Tape it. Hold the math in your hand. That’s where the real learning happens.