You’re sitting at a red light. The green flash hits, you stomp the pedal, and your back hits the seat. That's it. That is the physical manifestation of a change in velocity over time. Most people think acceleration is just "going fast," but in the world of physics, that’s a rookie mistake. Honestly, you could be slowing down and still be "accelerating" in the eyes of a physicist. It’s all about the rate of change.

If we’re being real, the acceleration formula is the backbone of almost everything that moves, from the vibrations of a smartphone haptic motor to the trajectory of a SpaceX Falcon 9. Without it, we're just guessing where things will land.

The Basic Math That Runs the World

Let's look at the standard version. Most textbooks will throw $a = \frac{\Delta v}{t}$ at you and expect you to just get it. But let’s break that down into human English. The little triangle ($\Delta$) is the Greek letter Delta, which just means "change." So, acceleration ($a$) is the change in velocity ($v$) divided by the time ($t$) it took for that change to happen.

Think about a car that goes from 0 to 60 mph in 3 seconds. To find the acceleration, you take the final speed (60), subtract the starting speed (0), and divide by the time (3). You get 20 mph per second. Simple, right? But here is where it gets kinda tricky: velocity isn't just speed. It has a direction. If you’re driving in a circle at a constant 30 mph, you are technically accelerating every single second because your direction is constantly shifting.

Why Vector Direction Matters

In physics, we call acceleration a vector quantity. This means it has both a magnitude (the number) and a direction (where it’s going). If you ignore the direction, your calculations for things like orbital mechanics or even high-speed cornering in a racing game like Assetto Corsa will be completely wrong.

🔗 Read more: Updating Your macOS: Why Most People Wait Too Long and How to Do It Right

Isaac Newton, the guy who basically wrote the rulebook on this, tied acceleration to force. His Second Law of Motion tells us that $F = ma$. This means force equals mass times acceleration. If you want to move a heavy truck (high mass) at a high acceleration, you need a massive amount of force. This is why a semi-truck has a giant engine compared to a Vespa, even if they both want to hit 30 mph.

Gravity: The Constant Accelerator

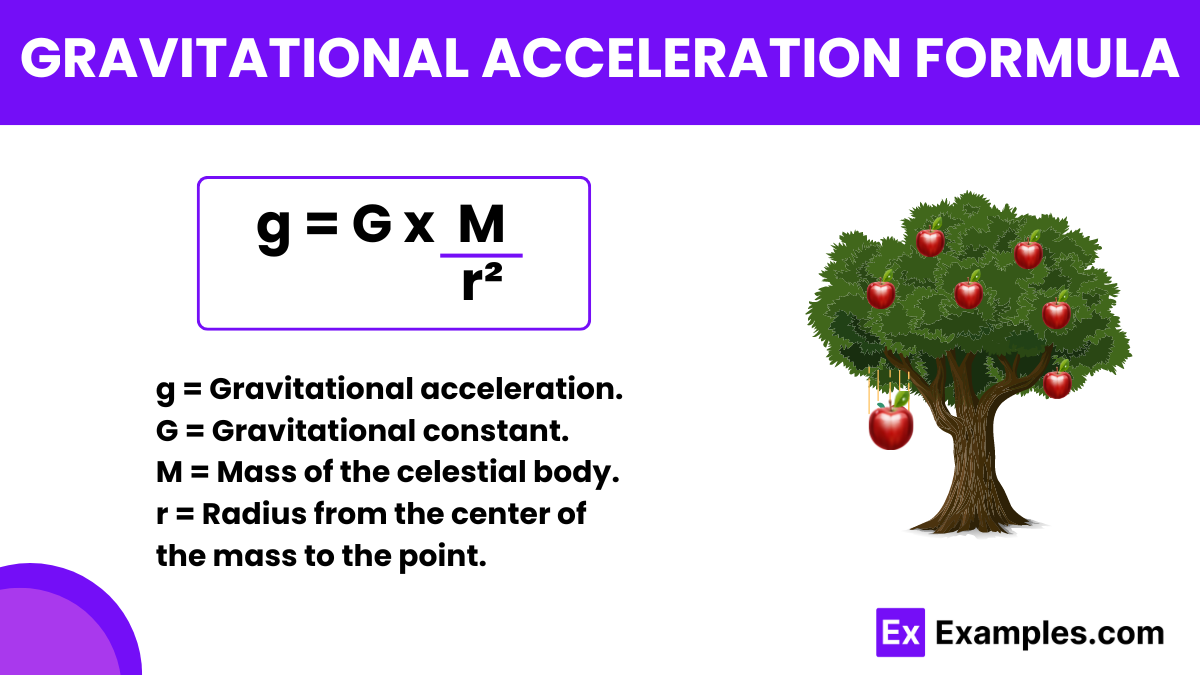

One of the most famous applications of the acceleration formula involves stuff falling out of the sky. Near the surface of Earth, gravity accelerates everything at roughly $9.8$ $m/s^2$. This is a constant we usually label as $g$.

Galileo famously (though maybe apocryphally) dropped balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to prove that mass doesn't actually change how fast things fall. In a vacuum, a bowling ball and a feather hit the ground at the same time. Why? Because the acceleration due to gravity is independent of the object's mass. The only reason the feather drifts slowly in your backyard is air resistance—a counter-force that messes with the "pure" physics of the formula.

The Problem With Variable Acceleration

In the real world, acceleration is rarely constant. When you launch a rocket, the mass of the rocket actually decreases as it burns fuel. This means that even if the engine's thrust stays the same, the acceleration actually increases as the rocket gets lighter. This is why rocket scientists use calculus. They have to calculate the "instantaneous acceleration" at every tiny fraction of a second.

If you’re looking at a graph of velocity over time, the acceleration is just the slope of the line. A steep slope means you're hauling. A flat line means you're moving at a constant speed—meaning your acceleration is exactly zero.

Centripetal Acceleration: Moving in Circles

Ever been on a roller coaster and felt like you were being pushed into the side of the car during a sharp turn? That's centripetal acceleration. Even if the coaster is moving at a steady 50 mph, the change in direction requires an inward acceleration toward the center of the curve.

The formula for this is slightly different: $a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}$.

Here, $r$ is the radius of the turn. This explains why sharp turns (small $r$) feel much more intense than wide ones. If you halve the radius of a turn while keeping your speed the same, the acceleration you feel actually doubles. This is a massive factor in civil engineering. When engineers design highway off-ramps, they use this math to make sure your car doesn't slide off the road because the required centripetal force exceeded the friction of your tires.

👉 See also: How Do I Block Photos on Facebook: What Most People Get Wrong

Beyond the Basics: Non-Uniform Motion

Most high school physics classes stick to "Uniformly Accelerated Motion." They use the "SUVAT" equations, named after the variables:

- $s$ (displacement)

- $u$ (initial velocity)

- $v$ (final velocity)

- $a$ (acceleration)

- $t$ (time)

But things get weird when we look at "Jerk." Yes, that’s a real scientific term. Jerk is the rate at which acceleration changes. If you’ve ever been in an elevator that starts or stops too abruptly, you felt a high level of jerk. Engineers work incredibly hard to minimize jerk in public transit to keep people from falling over. It's the "smoothness" factor of any ride.

Real-World Applications You Actually Care About

- Smartphone Airbags: Your phone has an accelerometer. It's a tiny chip that uses the acceleration formula to detect if the device is in free fall. If it detects that $a = 9.8$ $m/s^2$, it can trigger internal protections to park the hard drive head or prep for impact.

- Crash Safety: Car crumple zones are designed to increase the time it takes for a car to come to a stop during a wreck. If you look at $a = \frac{\Delta v}{t}$, increasing the time ($t$) makes the acceleration ($a$) smaller. Smaller acceleration means less force on your body, which is the difference between a bruise and a broken bone.

- Sports Science: Sprinters like Usain Bolt aren't just fast; they have incredible acceleration in the first 30 meters. Coaches use laser gates to measure exactly how many meters per second squared an athlete can produce from the blocks.

The Einstein Twist

We can't talk about acceleration without mentioning Albert Einstein. His "Equivalence Principle" suggests that you can't actually tell the difference between gravity and acceleration. If you were in a closed box in deep space and it was accelerating at $9.8$ $m/s^2$, you would feel like you were standing on Earth. This realization led him to the General Theory of Relativity. He figured out that gravity isn't just a force—it's actually the warping of spacetime caused by mass.

How to Calculate It Yourself

If you want to use the acceleration formula right now, you just need two data points of speed and the time between them.

Suppose you’re riding a bike. You start at 2 meters per second. Five seconds later, you’re at 12 meters per second.

The change in velocity is 10 (12 minus 2).

Divide that 10 by the 5 seconds it took.

Your acceleration is 2 $m/s^2$.

That means every single second, you were going 2 meters per second faster than the second before. It's an additive process.

Common Misconceptions to Avoid

People often confuse "high velocity" with "high acceleration." A bullet traveling at a steady 900 meters per second has zero acceleration. It's fast, but it's not accelerating. Conversely, a snail that starts moving from a dead stop has a measurable acceleration, even if its velocity is pathetic.

Another one is "deceleration." In physics, there's no such thing as deceleration as a separate concept. It’s just negative acceleration. If you’re moving in a positive direction and you slow down, your acceleration is negative. It keeps the math cleaner and prevents errors when you start plugging numbers into more complex formulas involving vectors and forces.

Practical Next Steps for Mastering Motion

To truly get a handle on how this works, start by observing it in your daily life. Next time you're in a car, pay attention to the speedometer and a stopwatch. Try to estimate your car's $0-60$ acceleration by using the formula.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Macbook 14 Inch Sleeve: Why Most People Buy the Wrong One

If you're a student or a hobbyist, download a "Physics Toolbox" app on your smartphone. These apps use the phone's built-in sensors to show you real-time graphs of your acceleration as you walk, run, or drive. Seeing the line spike as you jump or dip as you stop makes the abstract math feel a lot more tangible.

For those looking to go deeper, look into the relationship between acceleration and work-energy theorems. Understanding how acceleration translates into Kinetic Energy ($KE = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$) is the next logical step in seeing how the physical world stays in motion.