Biology is messy. It isn't just a collection of neat diagrams in a textbook you haven't opened since high school. It’s a high-stakes translation job happening inside your cells every single second. To understand how your body builds muscle, fights viruses, or grows hair, you have to look at the amino acid chart for mRNA.

Think of it as a Rosetta Stone. Without it, the "language" of your DNA is just a bunch of gibberish—a long string of A, C, G, and U that doesn't actually do anything until it’s turned into protein. This process is called translation. It's basically the most sophisticated manufacturing operation on the planet.

What the Amino Acid Chart for mRNA Actually Tells Us

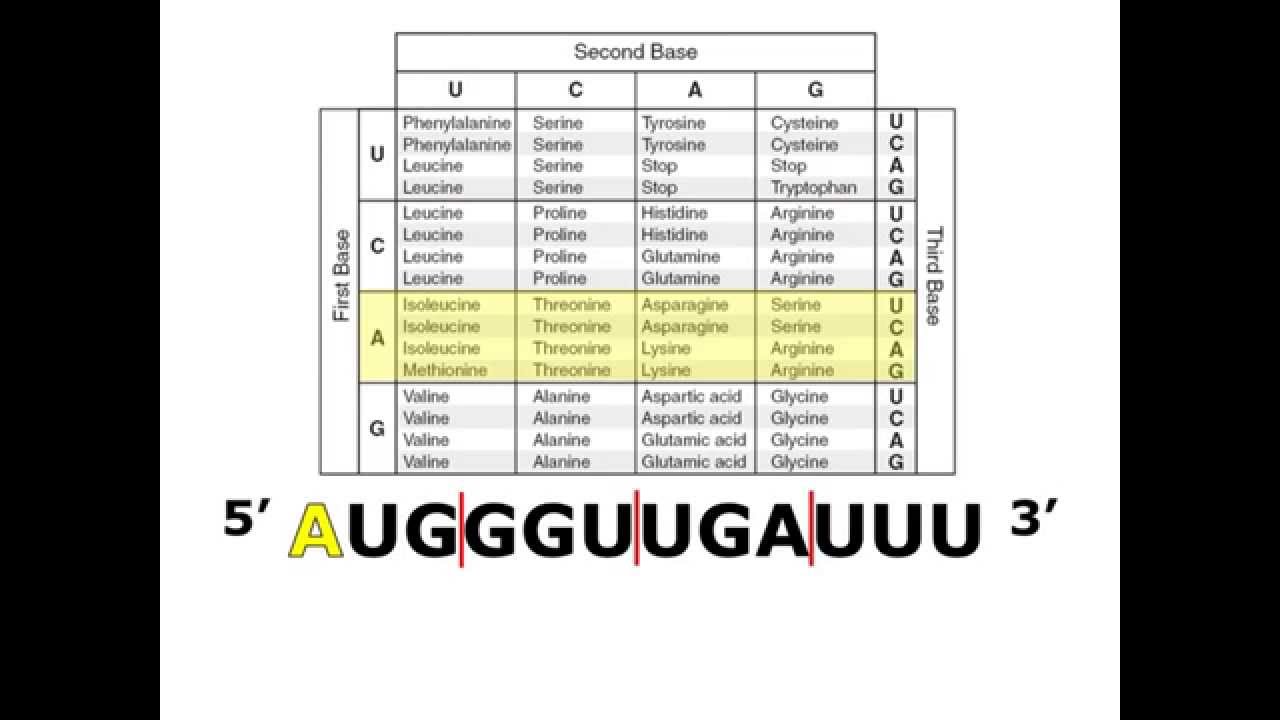

Most people look at a codon table and see a grid. It’s a 4x4 box, usually. Each box represents a combination of three nucleotides. These three-letter sequences are called codons.

If you have a sequence like AUG, the chart tells you that's Methionine. If you see UGG, that’s Tryptophan. It seems simple, right? It isn't.

The chart is actually a map of redundancy. There are 64 possible codon combinations but only 20 standard amino acids used by humans. This is what scientists like Francis Crick (who helped figure this out in the 1960s) called a "degenerate" code. That doesn't mean it’s immoral—it means it’s redundant. Multiple codons can code for the same amino acid. For instance, leucine has six different codons. SIX.

Why? Because mistakes happen.

If your mRNA gets a "typo" due to radiation or just a random glitch, having multiple ways to spell the same amino acid acts as a biological safety net. If CUU mutates into CUC, you still get Leucine. No harm, no foul. Your protein still works. This built-in error correction is why life hasn't just disintegrated into a pile of non-functional goo.

Reading the Chart Without Getting a Headache

You read these things from the inside out or from left to top to right.

- First Base: You find the first letter of your codon on the left side.

- Second Base: You look at the top of the chart for the second letter.

- Third Base: You narrow it down on the right side.

It's basically a game of Battleship, but the prize is a functional enzyme instead of a sunken destroyer.

The Start and Stop Signals

The most important parts of the amino acid chart for mRNA aren't even the amino acids themselves. They are the punctuation.

AUG is the big one. It’s the "Start" codon. Every single protein synthesis journey begins with AUG. It’s like the "Once upon a time" of molecular biology. It also codes for Methionine, which is why almost every new protein starts its life with a Methionine tail, though sometimes that gets clipped off later.

Then you have the "Stop" codons: UAA, UAG, and UGA. These don't code for amino acids. Instead, they signal the ribosome to stop building. They’re the "The End" at the end of the book. If a mutation creates a "Stop" codon too early—something called a nonsense mutation—you end up with a truncated, useless protein. This is what happens in certain types of muscular dystrophy. The protein is literally cut short because the ribosome hit a premature "Stop" sign.

Why the Circular Chart is Sometimes Better

You'll often see two versions: the square grid and the circular "sunburst" chart.

Honestly, the circular one is way more intuitive for beginners. You start in the center with the first letter and move outward. It mimics the way the ribosome "reads" the strand. You go from the 5' end to the 3' end.

If you're trying to decode a sequence like 5'-GCAUGC-3', you start at the G in the middle, move to the C in the next ring, and then the A in the third ring. Boom. Alanine.

The Nuance: It's Not Always Universal

Bio teachers love to say the genetic code is universal. From a bacteria in a gutter to a blue whale, the amino acid chart for mRNA is supposed to be identical.

That’s mostly true. But nature loves an exception.

In human mitochondria—the little powerhouses of your cells—the code is slightly different. For example, in the mitochondria, UGA doesn't mean "Stop." It actually codes for Tryptophan. This is a massive piece of evidence for endosymbiotic theory—the idea that mitochondria were once independent bacteria that got swallowed by a larger cell and decided to stay. They kept their own slightly weird version of the dictionary.

Real-World Applications: mRNA Vaccines and Beyond

We aren't just looking at these charts for fun or to pass a Bio 101 quiz. We are using them to rewrite medicine.

Take the mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. Scientists took the genetic sequence of the spike protein from the virus. They used the amino acid chart to work backward. They designed a piece of mRNA that would tell your cells to build that specific protein.

But here’s the cool part: they didn't just use the exact viral sequence. They used "codon optimization." Remember how I said the code is redundant? Some codons are "easier" for human cells to read than others. By picking the most efficient "spellings" for the amino acids, researchers ensured your cells would churn out enough protein to trigger a strong immune response. It’s like taking a manual written in clunky, old English and rewriting it into modern, snappy prose so the factory workers can build the product faster.

Misconceptions You Should Probably Drop

A big mistake people make is confusing mRNA with tRNA.

The chart is for mRNA. The tRNA is the physical bridge. It has an "anticodon" that is the mirror image of the mRNA. If the mRNA says AAA (Lysine), the tRNA has UUU. Don't look up UUU on the chart and think you're getting Phenylalanine. You always, always look up the mRNA sequence. The mRNA is the boss; the tRNA is just the delivery truck.

Another thing: the chart isn't the "code of life." DNA is the code of life. The mRNA chart is the translation of that code. DNA uses Thymine (T), but when it gets transcribed into mRNA, that T becomes a Uracil (U). If you're looking at a sequence with Ts in it, you're looking at DNA. Convert those Ts to Us before you even touch the chart.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Multi Plug Surge Protector Might Actually Be Killing Your Electronics

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student, a bio-hacker, or just a nerd, don't just memorize the 20 amino acids. That's a waste of brain space. Focus on the patterns.

- Hydrophobic amino acids tend to have a U in the second position (like Valine, Leucine, Isoleucine).

- Hydrophilic amino acids often have an A or G in the second position.

This means if a mutation swaps a letter but stays within the same "chemical family," the protein might still fold correctly. Biology is built with these layers of resilience.

Actionable Steps for Decoding Sequences

- Check the Orientation: Ensure your sequence is written in the 5' to 3' direction. If it's 3' to 5', flip it. Ribosomes only read one way.

- Find the Start: Don't just start at the first letter of the string. Scan until you find AUG. Anything before that is "untranslated region" (UTR).

- Group into Threes: Break the string into triplets.

- Identify the Stop: Keep going until you hit UAA, UAG, or UGA. Everything after that is also ignored by the ribosome.

- Verify the Mutation: If you’re looking at a SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism), check if it’s "synonymous." If the amino acid doesn't change, the mutation is likely silent and harmless.

Understanding the amino acid chart for mRNA isn't about rote memorization. It’s about seeing the logic in the chaos of the cellular world. It's the difference between seeing a string of letters and seeing the blueprint for a living, breathing organism.

Next time you see a sequence, don't just see letters. See the instructions for building a human. Check the redundancy, find the start, and respect the "Stop" codons. They’re there for a reason.