Let’s be real for a second. You’ve probably stared at a rotating disk problem or a block sliding down a frictionless ramp and felt that specific kind of academic despair that only College Board can induce. It's frustrating. You download an AP Physics 1 sample test, breeze through the kinematics, and then get absolutely bodied by a multi-part free-response question about angular momentum conservation.

Physics isn't just math with letters. It’s actually a linguistics course disguised as a science class. If you don't speak "College Board," you're going to struggle, even if you can derive every equation on the green sheet from memory.

The Trap of the Plug-and-Chug Mentality

Most students approach a practice exam like a math quiz. They see a variable, find an equation, and solve for $x$. That is exactly how you fail this exam. Since the 2015 redesign, and the more recent 2024-2025 curriculum updates, the focus has shifted almost entirely toward conceptual understanding and "physics sense."

✨ Don't miss: The Bell Cobra Attack Helicopter: Why It Still Matters Decades Later

When you look at an AP Physics 1 sample test, notice how many questions don't even have numbers. They ask what happens to the acceleration if the mass doubles while the force stays constant. Or they ask you to "justify your answer" in a paragraph. If you’re spending all your time on a calculator, you’re practicing for a version of the test that hasn't existed for a decade.

Take the classic "Atwood Machine" setup. A standard textbook might ask for the tension. An actual AP question will ask how the center of mass of the system moves if one pulley is replaced with a massive, frictional one. It’s mean. It’s tricky. But it’s how they separate the "calculators" from the "physicists."

Deciphering the Free-Response Questions (FRQ)

The FRQ section is where dreams go to die, mostly because of the "Paragraph Argument Short Answer" question. You have to write a coherent paragraph explaining a physical phenomenon without using a single equation as your primary proof.

The Experimental Design Hurdle

You’ll almost certainly see a question asking you to design an experiment. This is a staple of any AP Physics 1 sample test. You need to list the equipment, the procedure, and how you’ll analyze the data to find a specific value, like the coefficient of static friction.

Pro tip: always mention multiple trials. If you don’t say you’re going to repeat the experiment to reduce experimental error, you’re leaving points on the table. It’s a trope at this point, but it’s a mandatory one. Also, remember that you can’t just say "measure the force." You have to say "use a spring scale or a force sensor to measure the force." Specificity is everything.

Qualitative/Quantitative Translation

This is a fancy way of saying "show me the math, then tell me what it means in English." You might have to derive an expression for velocity, like:

$$v = \sqrt{\frac{2gh}{1 + \frac{I}{mR^2}}}$$

Then, the very next part will ask how the final velocity changes if the object is a hoop instead of a solid cylinder. If you can't explain that a hoop has more rotational inertia ($I = mR^2$) and therefore "steals" more energy from translation to rotation, the math won't save you.

Rotational Dynamics: The Silent Killer

Ask any teacher. Torque and Rotation are the hardest parts of the course. Period. Most AP Physics 1 sample test materials lean heavily into this because it combines everything: kinematics, Newton’s Laws, and Energy.

When an object rolls without slipping, it's doing two things at once. It’s moving forward, and it’s spinning. If you forget to account for the rotational kinetic energy $K_{rot} = \frac{1}{2}I\omega^2$, your energy conservation equation is wrong. This is the most common error on the exam.

Honestly, it’s kinda cruel that they put this at the end of the year when everyone is already burned out. But because it accounts for a significant chunk of the weight (usually 12-18%), you can’t ignore it. You've got to be comfortable with the relationship between linear and angular variables. If you don't know that $v = r\omega$ and $a = r\alpha$, you’re basically guessing.

Energy and Momentum are Your Best Friends

Whenever you're stuck on a problem in an AP Physics 1 sample test, ask yourself: "Can I use Energy or Momentum?"

- Is there a collision? Use Conservation of Momentum.

- Is there a change in height or speed? Use Conservation of Energy.

- Is there a force acting over a distance? That’s Work.

- Is there a force acting over a time? That’s Impulse.

A lot of students try to use Kinematics for everything. But Kinematics only works if the acceleration is constant. In the real world (and on the AP exam), acceleration is rarely constant. If a spring is involved, the force changes as the spring compresses ($F = -kx$). Kinematics is useless there. You need Energy.

The 2025 Curriculum Shift

Starting with the 2024-2025 school year, AP Physics 1 actually expanded. They brought back "Fluids." It used to be in AP Physics 2, but now it’s back in Physics 1. This means your older AP Physics 1 sample test PDFs from 2021 might be missing an entire unit.

You need to know:

- Density and Specific Gravity

- Pressure at depth ($P = P_0 + \rho gh$)

- Buoyancy and Archimedes’ Principle

- Bernoulli’s Equation (the big one)

If your practice material doesn't have a question about a wood block floating in water or oil, it’s outdated. Throw it away. Get something current.

How to Actually Use a Sample Test

Don't just sit down and do the whole thing in one go the first time. That's a waste of a good resource.

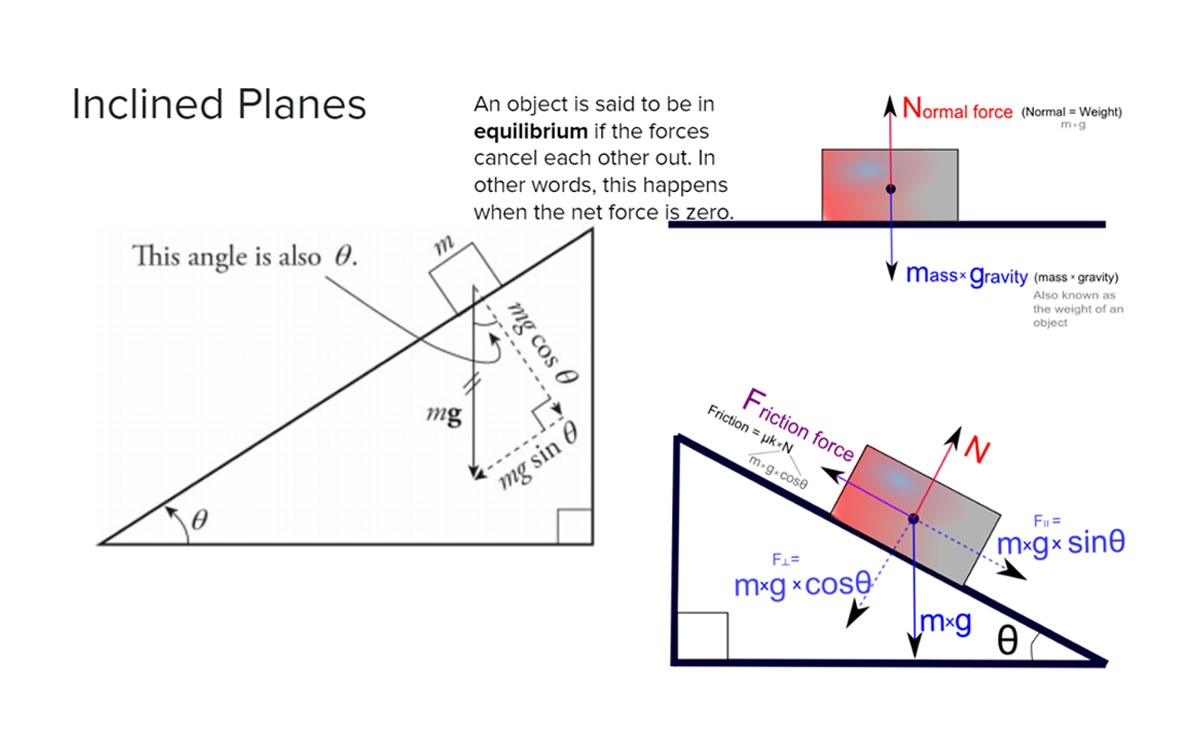

Break it up. Do the Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) for Unit 1 and 2. See where you tripped up. Did you forget that the normal force isn't always $mg$? (It's not, especially on an incline or if someone is pushing down on the object).

Once you’ve mastered the units individually, then do a timed run. The timing is tight. You have 90 minutes for 40 MCQs and 90 minutes for 4 FRQs (under the new format). That’s not a lot of time to sit and ponder the mysteries of the universe. You need to recognize patterns instantly.

Real Talk on the "Five"

Getting a 5 on the AP Physics 1 exam is statistically harder than almost any other AP exam. The curve is generous, but the raw scores are usually low. You don't need a 90% to get a 5. Often, a 65-70% total score will land you that top spot.

This should give you permission to breathe. You can get things wrong. You can totally blank on a part of an FRQ and still come out on top. The goal is "partial credit." Never leave an FRQ blank. Write down a relevant equation. Draw a Free Body Diagram (FBD). If the question asks for a graph, draw something—even if you're not sure if it's linear or parabolic. A slope in the right direction is often worth a point.

Actionable Next Steps

To actually see improvement, stop reading and start doing. Here is exactly what you should do next:

- Audit your resources. Ensure your AP Physics 1 sample test includes Fluids. If it doesn't, go to the College Board website and download the most recent "Course and Exam Description" (CED). It has the most accurate sample questions available.

- Master the FBD. If you can't draw the forces correctly, you can't write the $F_{net} = ma$ equations. Remember: never "break" forces into components on the actual FBD you submit for grading. Draw them original, then do your components on a separate scratchpad.

- Practice the Paragraph. Find three FRQs that require a "Paragraph Argument." Write them out. Read them aloud. If they don't make sense to someone who doesn't know physics, they probably aren't clear enough for the grader.

- Check the Units. Sounds stupid, right? But the number of people who lose points because they didn't convert grams to kilograms or centimeters to meters is staggering. Physics happens in SI units. Stick to them.

- Watch "Flipping Physics." If you're stuck on a concept, Billy, Bobby, and Bo are the gold standard for AP Physics 1 prep. They follow the curriculum exactly and use the right terminology.

Physics is a mountain. You don't climb it by staring at the peak; you climb it by looking at your feet and taking the next step. Grab a pencil, pull up a problem, and start grinding.