Mac gaming used to be a punchline. For decades, if you wanted to play the latest AAA titles, you bought a PC or a console, period. Apple’s transition to Silicon changed the hardware narrative, but the software gap remained a canyon. Then came the Apple Game Porting Toolkit. It wasn't just another API update. It was a massive, unexpected shift in how developers—and tech-savvy gamers—look at macOS as a viable home for high-end gaming.

Basically, Apple did something they almost never do: they embraced an open-source foundation to solve a proprietary problem.

What is the Apple Game Porting Toolkit?

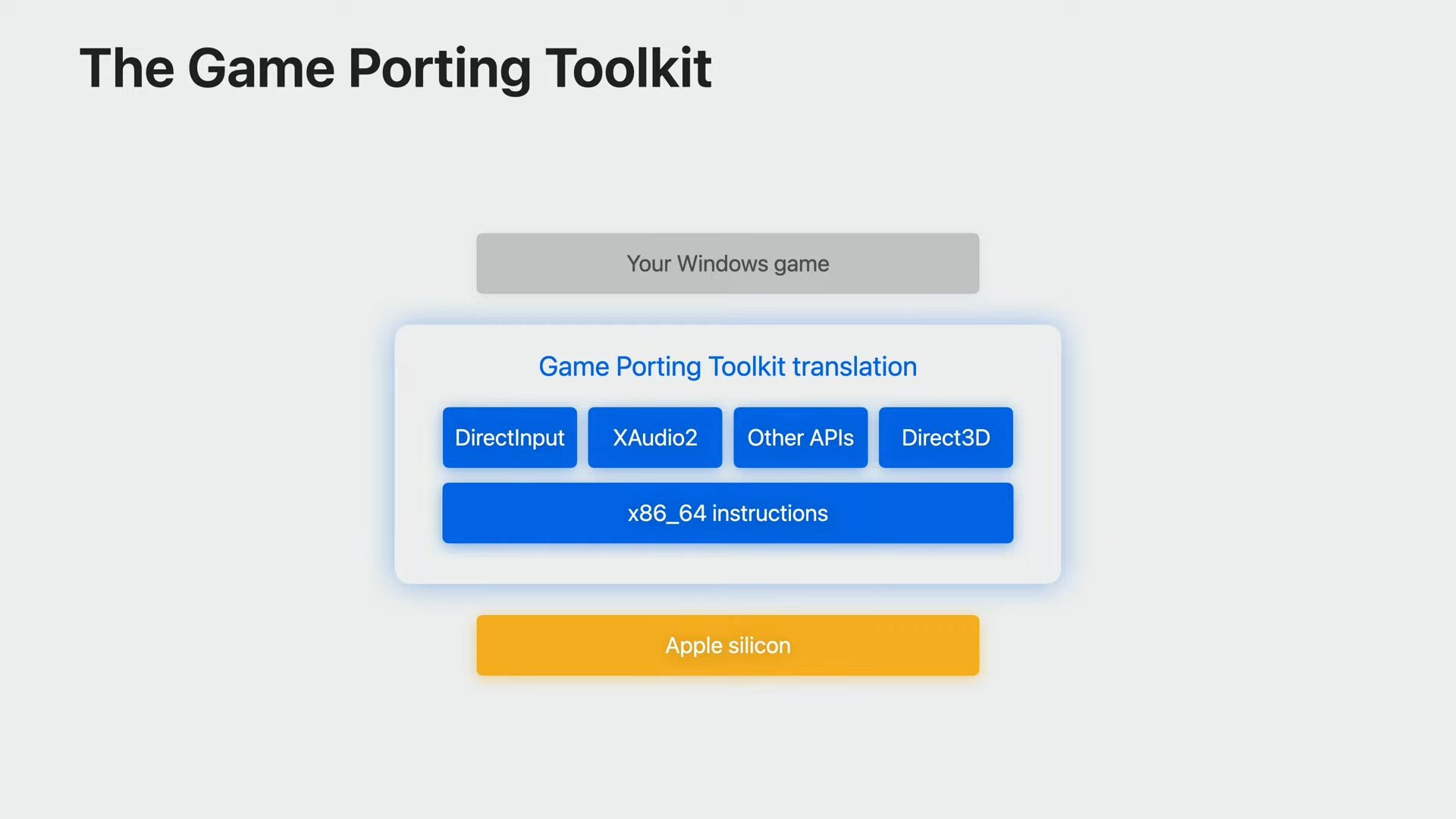

At its core, the Apple Game Porting Toolkit (GPTK) is a set of tools designed to help developers move Windows games to the Mac with as little friction as possible. But that's the corporate definition. In reality, it’s a translation layer. It takes code written for DirectX 12—Microsoft's secret sauce for Windows gaming—and translates it on the fly to Apple's Metal 3.

The shocker at WWDC was that Apple used source code from CrossOver, which is built on Wine. Seeing Apple acknowledge Wine was like seeing a high-end fashion designer admit they use thrift store fabrics to prototype their next runway line. It works. It works surprisingly well.

The technical magic under the hood

The toolkit isn't just one thing. It's a multi-part bridge. First, there's the emulation environment. This allows a developer to take an unmodified Windows .exe file and just... run it. No porting, no rewriting code, no massive engineering overhead. You drop the game into the environment, and the Apple Game Porting Toolkit handles the heavy lifting of translating x86 instructions to ARM and DirectX calls to Metal.

It’s not perfect. You’ll see some overhead. But for a developer wondering if it's worth spending $500,000 on a native Mac port, being able to see their game running at 40 FPS on an M2 Max in ten minutes is a game-changer. It’s a "vibe check" for software.

💡 You might also like: Why Jill Valentine in Resident Evil 3 is Still the Gold Standard for Horror Protagonists

Why GPTK 2 is a massive leap forward

A year after the first version dropped, Apple released GPTK 2. This wasn't just a bug fix. They added support for AVX2, which was a huge sticking point for modern titles that rely on complex instruction sets. If you tried to run certain modern games on the first version, they simply crashed. Now? They breathe.

Honestly, the most impressive part of the second iteration is the improved ray tracing support and the way it handles spatial audio. Apple is trying to prove that the Mac isn't just "capable" of running games, but that the M-series chips offer features that Windows laptops struggle to match in terms of efficiency.

More than just a "Wine wrapper"

People call it a wrapper. That's a bit reductive. While the evaluation environment uses Wine, the toolkit also includes a massive suite of header converters and a Metal Shader Converter. This is the real "expert" tool. It automatically converts thousands of HLSL (High-Level Shader Language) shaders into Metal. Shaders are the soul of a game's visual identity. Converting them manually is a nightmare that takes months. GPTK does it in seconds.

The "End User" loophole

Apple intended the Apple Game Porting Toolkit for developers. They wanted studios like Capcom or Ubisoft to use it as a stepping stone to build native ports like Resident Evil Village or Death Stranding.

But the internet is the internet.

Within 48 hours of the toolkit’s release, gamers figured out how to use it to run Cyberpunk 2077, Elden Ring, and Spider-Man on their MacBooks. It’s not a seamless "click and play" experience. You have to mess with Terminal. You have to install Homebrew. You might have to sacrifice your Saturday afternoon to a wall of text. But seeing Cyberpunk running on a machine that doesn't have a fan? That's magic.

Real-world performance expectations

Don't expect miracles. If you're running the Apple Game Porting Toolkit to play a Windows game, you're losing performance in the translation. You might get 60% to 70% of the native hardware's potential. An M3 Max is a beast, but even it struggles when it has to translate DirectX 12 to Metal in real-time while also emulating x86 architecture.

- M2/M3 Base Chips: Good for older titles or indie games.

- Pro Chips: The sweet spot for 1080p gaming on modern titles.

- Max/Ultra Chips: This is where you can actually push 1440p or 4K with decent frame rates.

What most people get wrong about Mac gaming

The biggest misconception is that the Mac "can't" run games because of the hardware. That's been false since the M1 debuted. The problem was the "Metal" tax. Developers didn't want to rewrite their entire rendering engine for a platform that represented 10% of the market.

The Apple Game Porting Toolkit eliminates the "I wonder if it will work" phase of development. It provides a proof of concept instantly. This is why we are seeing a sudden surge in native Mac ports. It's not that Apple suddenly started paying everyone; it’s that Apple made it cheap and easy to see the potential.

The Sonoma and Sequoia factor

Apple also integrated a "Game Mode" into macOS Sonoma and refined it in Sequoia. When the Apple Game Porting Toolkit is running, Game Mode kicks in to give the process highest priority on the CPU and GPU. It also doubles the Bluetooth sampling rate for controllers. It’s a holistic approach. They aren't just throwing a tool at devs; they're prepping the OS to be a better host.

How to actually use it (The non-developer way)

If you aren't a dev but want to try this, you'll likely want to use a third-party tool that simplifies the GPTK. Tools like Whisky or CrossOver 24 are the way to go.

- Whisky: This is a clean, simplified wrapper for the Apple Game Porting Toolkit. It's free and open-source. You don't need to know Terminal commands. You just create a "bottle," install Steam for Windows inside it, and try your luck.

- CrossOver: This is the "pro" version. It’s paid, but they contribute back to the Wine project and have their own optimizations that often outperform the raw toolkit.

The roadmap for the future

We are currently in a transitional era. The Apple Game Porting Toolkit is a bridge, not a destination. Apple's ultimate goal is for you to buy games on the Mac App Store that run natively. They want the iPad, iPhone, and Mac to share a single gaming ecosystem.

The toolkit is the lure. It proves to the big studios that the M-series chips are effectively "consoles" hidden inside laptops. When you realize there are tens of millions of M-series Macs in the wild, the market suddenly looks a lot bigger than it did in the Intel days.

Nuance and limitations

Let’s be real for a second. Anti-cheat software is the final boss for the Apple Game Porting Toolkit.

Games like Valorant, Call of Duty, or Apex Legends use kernel-level anti-cheat. These will likely never work through GPTK or any translation layer. They require deep system access that macOS simply won't grant to a Windows emulation environment. If your favorite game relies on Ricochet or Vanguard, the toolkit won't help you. You're still going to need a PC.

Actionable insights for Mac owners

If you're sitting on a Silicon Mac and want to see what the Apple Game Porting Toolkit can do for you, don't start with the raw command-line tools unless you're a glutton for punishment.

Start with Whisky. It’s the most user-friendly gateway. Download it, grab a Windows game you already own on Steam, and see how it runs.

Check compatibility databases. Before you buy a game specifically to play via GPTK, check the AppleGamingWiki. It's a community-driven site that tracks exactly which games work, which ones glitch, and which ones are a total "no-go."

Manage your thermals. Even though Silicon is efficient, translation layers are resource-heavy. If you're on a MacBook Air, you’re going to hit thermal throttling much faster than you would with a native app. Keep your sessions shorter or play in a cool environment.

The gap between Windows and Mac gaming isn't closed, but for the first time in twenty years, there's a visible path to the other side. Apple stopped asking developers to come to them and finally built the road themselves.