Physics is weirdly deceptive. We grow up thinking speed and velocity are the same thing, but they aren't. Not even close. If you run a full lap around a track and end up exactly where you started, your average speed might be impressive, but your average velocity is technically zero.

Does that sound like a scam? It kinda is, at least from a mathematical perspective.

When you’re looking for the equation for average velocity, you’re really asking how far an object moved from its starting point in a specific direction over a set amount of time. It’s about the "net" change. Most people trip up because they confuse distance with displacement. In the world of physics—the one governed by people like Newton and taught by modern educators like Dr. Walter Lewin—displacement is the only thing that matters for this specific calculation.

What is the Equation for Average Velocity?

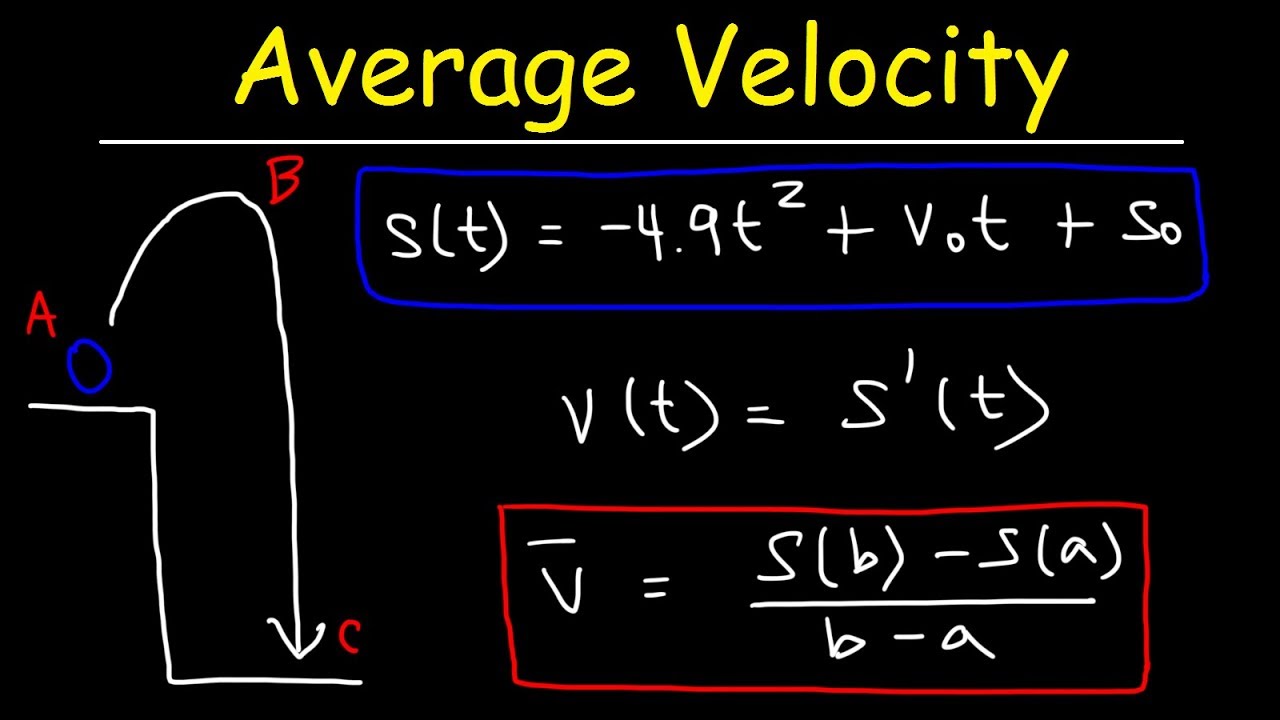

The formula is straightforward, yet it carries a lot of weight. Basically, it’s the change in position divided by the change in time.

In formal notation, we write it as:

$$v_{avg} = \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta t}$$

To break that down into plain English: $v_{avg}$ is your average velocity. The Greek letter delta ($\Delta$) just means "change in." So, $\Delta x$ is your change in position (displacement), and $\Delta t$ is the time it took for that change to happen.

Let’s say you’re driving from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. If you take a massive detour through Phoenix for some reason, your odometer (distance) will show a huge number. But your displacement—the $\Delta x$ in our equation—is just the straight-line measurement from LA to Vegas. Velocity doesn't care about your scenic route. It only cares about the finish line relative to the starting blocks.

The Vector Problem

Velocity is a vector quantity. This is a fancy way of saying it has a direction. Speed is a scalar; it’s just a number. If you tell me you're going 60 mph, that's speed. If you tell me you're going 60 mph North, now we’re talking about velocity.

This distinction is why the equation for average velocity can sometimes result in a negative number. If we decide that "right" or "East" is the positive direction, and you move to the "left" or "West," your velocity is negative. It’s not that you’re going "slower than zero." It just means you’re headed in the opposite direction of the established coordinate system.

💡 You might also like: Virginia Tech Su Yu: The Real Story Behind the Nanomaterials Research

Breaking Down Displacement ($\Delta x$)

You can’t master the velocity formula without obsessing over displacement for a second. Displacement is defined as:

$$x_{final} - x_{initial}$$

Imagine a number line. You start at point 2 and move to point 10. Your displacement is 8. Easy. But if you start at 10 and move back to 2, your displacement is -8.

This is where the real-world application gets interesting. In GPS technology and autonomous vehicle programming, engineers have to constantly differentiate between "path length" and "displacement." A self-driving Tesla doesn't just need to know how fast the wheels are turning (speed); it needs to calculate its velocity vector to ensure it's actually moving toward its destination and not just spinning in a ditch.

Why Time Intervals Matter

The $\Delta t$ part of the equation is usually the easiest to find, but it’s where the "average" part of average velocity comes from.

Suppose you drive 100 miles. It takes you two hours. Your average velocity is 50 mph. But you weren't going 50 mph the whole time, right? You stopped for a coffee. You hit a red light. You maybe sped a little on the highway.

Average velocity is a "big picture" metric. It ignores the tiny fluctuations. If you want to know how fast you were going at the exact moment you passed a police officer, you’re looking for instantaneous velocity. To find that, you’d need calculus to shrink $\Delta t$ down until it’s almost zero. But for most of us doing homework or planning a road trip, the average is plenty.

A Real-World Example: The Olympic Sprinter

Let's look at Usain Bolt. In his 2009 world record 100-meter dash, he finished in 9.58 seconds.

Using our equation for average velocity:

- $\Delta x$ = 100 meters

- $\Delta t$ = 9.58 seconds

- $v_{avg} = 100 / 9.58 \approx 10.44$ meters per second.

Now, if Bolt ran that 100 meters in a straight line (which he did), his average speed and the magnitude of his average velocity are the same. But if the race was on a circular track and he ended exactly where he started, his average velocity would be 0 m/s. It feels wrong because he worked so hard, but the math doesn't lie. Displacement would be zero.

Common Pitfalls and Calculation Errors

Honestly, most people fail physics problems not because they don't know the math, but because they forget to check their units.

If your displacement is in kilometers and your time is in minutes, your velocity is in km/min. That’s rarely what a teacher or a professional report wants. Standard SI units are meters per second ($m/s$).

🔗 Read more: Sony WH-1000XM4 Sale: Why This Old Pair is Actually Better Than the New Model

- Always convert first. If you have 5 km, call it 5,000 meters.

- Watch the signs. If an object moves backward, that negative sign is mandatory.

- Total time includes stops. If a bird flies for 10 minutes, rests for 5, and flies for 10 more, $\Delta t$ is 25 minutes. The rest time counts.

Average Velocity vs. Average Speed

I can’t stress this enough: they are different.

Average Speed = Total Distance / Total Time

Average Velocity = Total Displacement / Total Time

Think of a person walking 3 meters East and then 4 meters West.

- Total distance: 7 meters.

- Total displacement: 1 meter West (or -1 meter).

- Average speed will be much higher than average velocity here.

The Role of Constant Acceleration

Things get a bit spicy when acceleration is involved. If an object is accelerating at a constant rate, there is a shortcut to find the average velocity. You can just average the initial and final velocities:

$$v_{avg} = \frac{v_i + v_f}{2}$$

But be careful. This only works if the acceleration is uniform. If you’re stomping on the gas and then hitting the brakes randomly, this shortcut will give you a junk answer. Stick to the displacement/time formula unless you're absolutely sure the acceleration is a steady, unchanging value.

Why Does This Matter Outside of a Classroom?

You might think average velocity is just for textbook problems. It's not.

In logistics, companies like FedEx use these calculations to optimize routes. They aren't just looking at how fast a plane flies; they are looking at the displacement between hubs to calculate the most efficient "velocity" of a package across the globe.

In sports science, coaches use wearable GPS trackers to monitor a player's average velocity during a game. If a midfielder's average velocity drops in the second half, it’s a data-backed sign of fatigue, even if they’re still "running" a lot of distance.

📖 Related: Interstellar Travel: Why We Aren't There Yet (and When We Might Be)

Even in finance, people use the concept of "velocity of money." It’s a metaphorical use of the term, but it describes the rate at which money moves through the economy. The core idea is the same: how fast is something moving from Point A to Point B over a specific period?

How to Calculate Average Velocity in 3 Steps

If you're staring at a word problem right now and feeling stuck, just follow this flow.

- Identify the start and end points. Forget everything that happened in the middle. Where did it start? Where did it stop? Subtract the start from the end to get $\Delta x$.

- Find the total clock time. From the very first movement to the very last. That’s your $\Delta t$.

- Divide. Take your result from step 1 and divide it by step 2.

If the object moved in the negative direction, keep that negative sign. It’s important.

Practical Insights for Moving Forward

Understanding the equation for average velocity is basically your entry ticket into the world of kinematics. Once you've got this down, you can start looking at acceleration (the rate at which velocity changes) and eventually force and energy.

If you're working on a project or studying, start by sketching a simple position-time graph. The slope of the line connecting two points on that graph is the average velocity. If the line is steep, the velocity is high. If the line is flat, the object is stationary. If it slopes downward, you're looking at negative velocity.

To really nail this concept, try calculating your own average velocity on your next commute. Check your starting "pin" on a map, check your ending "pin," find the straight-line distance, and divide by the time it took. You’ll likely find your velocity is surprisingly low compared to the speed you saw on your speedometer.

Next Steps for Mastery:

- Practice converting units (mph to m/s is a classic).

- Draw a vector diagram for any problem involving two different directions.

- Experiment with a "position-time" graph to see how velocity appears visually.

The math is simple. The logic is where the magic happens. Once you stop thinking about "how fast" and start thinking about "how much change in position," physics starts making a whole lot more sense.