It is the meanest song he ever wrote. No contest. When you drop the needle on side two of Another Side of Bob Dylan, you eventually hit a track that feels less like a folk song and more like an open wound. Ballad in Plain D isn't just a breakup song; it is a public flaying. It’s raw. It’s uncomfortable. Honestly, it’s a little bit terrifying if you’ve ever been on the receiving end of a partner's rage.

Dylan recorded this in a single night in June 1964. He was reportedly fueled by a fair amount of Beaujolais. You can hear it in the performance. The song stretches over eight minutes, abandonning the surrealism of "Chimes of Freedom" for a brutal, literal play-by-play of the night his relationship with Suze Rotolo finally disintegrated. It’s a fascinating, ugly piece of music history.

✨ Don't miss: Why the After Next Generation Trailer Is Actually a Milestone for Indie Animation

The Night the Music Died in Greenwich Village

The "characters" in the song aren't metaphors. They were real people living in a small apartment on West 4th Street. You have Suze Rotolo—the "multitudes" of a girl who graced the cover of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan—and her sister, Carla. In the song, Carla is the "parasite." That’s a heavy word. Dylan doesn't hold back, describing her as someone who "stalked through the door" and "hypnotized" her sister.

The reality was a messy family intervention. Suze was tired. Dylan was becoming a global icon, which is a nice way of saying he was becoming impossible to live with. Carla Rotolo was an assistant to Alan Lomax and a sophisticated figure in the folk scene herself; she saw Dylan as a manipulative, often cruel presence in her sister's life. On that particular night, things turned physical. There was shouting. There was shoving. Dylan was eventually kicked out, and the relationship was done.

Most songwriters would write a vague tune about "lost love." Not 1964 Dylan. He went into Columbia Studios and named names, even if he masked them slightly behind the "Plain D" tuning. He used his platform to get the last word. It’s the ultimate "diss track" before that term even existed.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind Signs Five Man Electrical Band and Why the Lyrics Still Burn Today

Why the Lyrics Still Sting Decades Later

The structure is hypnotic. It’s a repetitive, circular melody that feels like a person pacing around a room, unable to stop obsessing over a grievance. He goes through the "friends and the councilors" who he felt were conspiring against him.

One of the most jarring lines is his description of Suze’s mother and sister: "The her and the she and the it that you live with." He deplanes them. He turns them into objects. It’s a brilliant piece of writing because it perfectly captures the tunnel vision of a bitter breakup. When you're that angry, your ex-partner's family isn't human anymore; they are just obstacles.

But there’s a flicker of self-awareness that people often miss. In the final verse, he asks the question that every person in a toxic situation eventually asks: "Are birds free from the chains of the skyway?" It’s a rare moment of philosophical doubt in a song otherwise defined by certainty and blame.

The 1985 Regret: Dylan Looks Back

If you think the song is harsh, you aren't alone. Bob Dylan eventually agreed with you. In a 1985 interview with Cameron Crowe for the Biograph box set, Dylan was surprisingly candid. He didn't defend the song. He didn't call it "artistic expression."

He called it a mistake.

"I must have been a real jerk to write that," he told Crowe. He admitted that of all the songs he’d written, that was the one he probably shouldn't have recorded. It’s a rare moment of Dylan looking in the rearview mirror and flinching. He realized that using a recording studio to settle a domestic dispute was, perhaps, a bit much.

Carla Rotolo, for her part, never really forgave him. And why should she? She was immortalized as a "parasite" in a song that millions of people would listen to for the next sixty years. In the folk world, reputation was everything, and Dylan used his genius to incinerate hers. It’s a reminder that great art doesn't always come from a "good" place. Sometimes it comes from the most petty, vindictive corners of the human heart.

A Technical Look at "Plain D"

Musically, the song is a marathon. Most pop songs are three minutes. This is eight. It’s just Dylan and his Gibson, fingerpicking in a way that feels urgent.

- The Tuning: Despite the title, the song is actually played with a capo on the second fret, using fingerings that would be in the key of C, resulting in the sound of D.

- The Vocal: His voice is nasal, sharp, and weary. You can hear the exhaustion of the "protest" era bleeding into the personal era.

- The Absence of a Chorus: There is no hook. There is no "Like a Rolling Stone" moment to shout along to. It is a narrative monologue.

This lack of traditional structure is what makes it so immersive. You can't escape the story. You are trapped in that apartment with them, watching the lamp get knocked over and hearing the door slam.

The Legacy of the "Protest" Against the Self

Another Side of Bob Dylan was a pivot point. The fans wanted more songs like "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll." They wanted Dylan to be the voice of the Civil Rights movement. Instead, he gave them Ballad in Plain D.

🔗 Read more: Where Can I Watch New Blood: Why It’s Actually Harder to Find Than the Original Series

He was essentially saying, "I’m not your leader; I’m a mess."

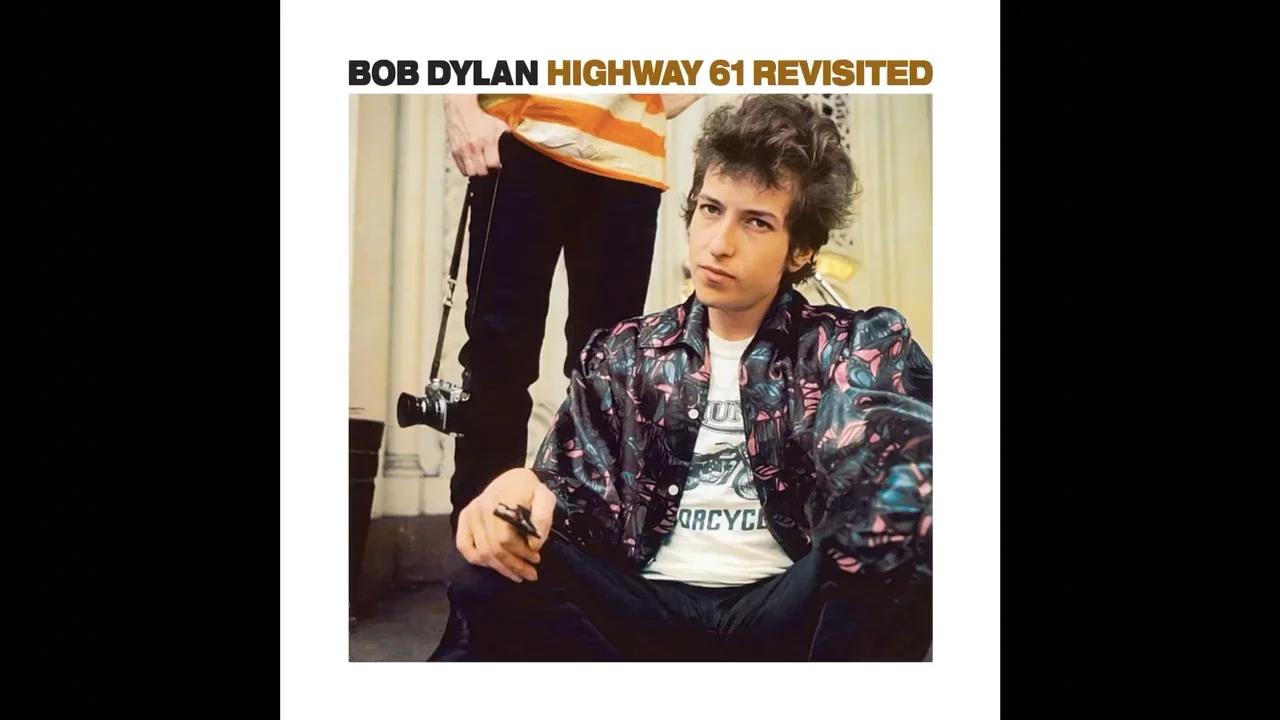

By airing his dirty laundry so violently, he broke the "folk hero" mold. He showed that he was capable of being unfair, sexist, and cruel. It’s an essential track for anyone trying to understand the transition from the "Woody Guthrie clone" to the "Electric Rock Star." You had to have the scorched earth of "Plain D" to get to the surrealist detachment of Highway 61 Revisited.

Actionable Insights for the Dylan Fan or Historian

If you want to truly understand the gravity of this track, don't just stream it on Spotify. Context matters here more than with almost any other song in his catalog.

- Read Suze Rotolo's Memoir: Pick up A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. She gives her side of the story without the vitriol Dylan used. It provides a necessary balance to the "parasite" narrative.

- Listen to the Outtakes: Check out the The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964. You can hear the transition in his persona during this year. The contrast between his stage presence and the raw bitterness of the Another Side sessions is startling.

- Analyze the Sequence: Listen to the song immediately followed by "It Ain't Me, Babe." The latter is the "clean" version of the breakup—the poetic, universal goodbye. "Ballad in Plain D" is the crime scene photo.

- Study the Lyrics as Prose: Strip away the music and read the lyrics. Notice how Dylan uses "stark" imagery. It’s a masterclass in narrative songwriting, even if the subject matter is regrettable.

Ultimately, Ballad in Plain D remains a landmark of "confessional" songwriting before that was a standard genre. It’s a warning of what happens when the line between life and art disappears entirely. It isn't a "pleasant" listen, but it is an honest one—perhaps a little too honest for Dylan’s own comfort.