You’ve probably seen the clips. A pitch-black shape suddenly transforms into a neon-blue, gaping mouth, or a bird with wires coming out of its head starts doing a frantic side-shuffle on a mossy log. It looks like a glitch in the Matrix. It’s actually a birds of paradise bird just trying to get a date. Honestly, if you haven't fallen down a YouTube rabbit hole of David Attenborough whispering about these things, you’re missing out on the weirdest show on Earth.

Most people think these birds are just "pretty." That's a massive understatement. Evolution usually cares about survival—finding food, not getting eaten, keeping warm. But for the Paradisaeidae family, survival is almost an afterthought. In the dense, fruit-rich jungles of New Guinea and parts of Australia, these birds have so much food and so few predators that they’ve basically spent the last few million years in an arms race of sheer ridiculousness.

The Absolute Absurdity of the Birds of Paradise Bird

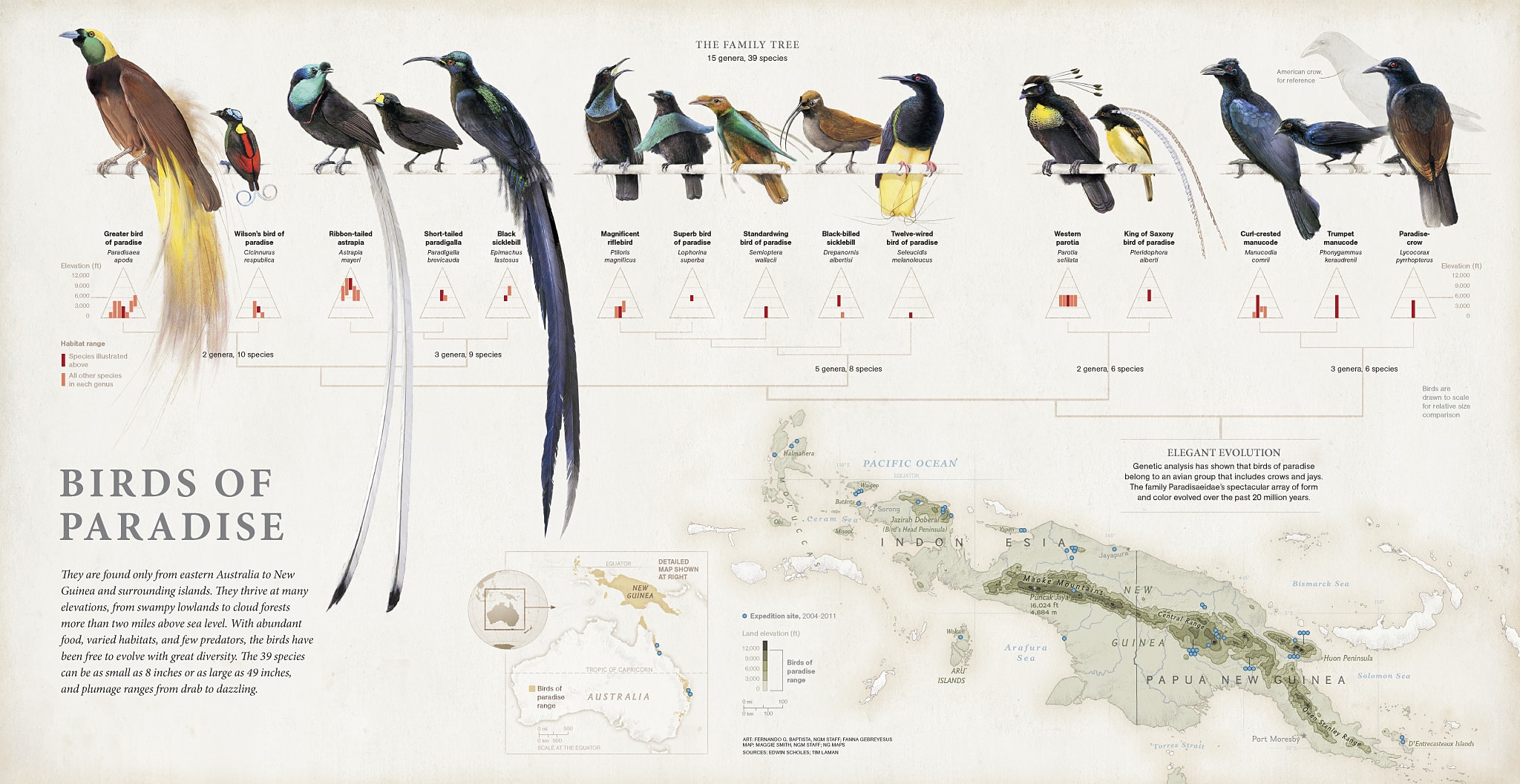

There are 42 species. Each one is weirder than the last. You have the Greater Bird of Paradise with its cascading yellow plumes, and then you have the Wilson’s Bird of Paradise, which looks like it’s wearing a tiny, turquoise yarmulke with a cross-hatch pattern. It's wild. The diversity isn't just for show; it's a result of reproductive isolation. Since New Guinea is incredibly mountainous, different groups of birds got stuck in isolated valleys. They couldn't mix.

So, they specialized.

Take the King of Saxony bird of paradise. It has two incredibly long, scalloped feathers sticking out of its head that look like Victorian-era radio antennas. It can move them independently. Imagine trying to fly through a thick jungle with two-foot-long sticks glued to your forehead. It’s a massive handicap. But that’s exactly the point. The female looks at him and thinks, "If he can survive looking that ridiculous, he must have some seriously good genes." Biologists call this the Handicap Principle. It’s the ultimate flex.

Why the Colors Look "Wrong" (In a Good Way)

Have you ever noticed how some of these birds look darker than a black hole? That’s not an exaggeration. Researchers at Harvard and the Smithsonian, including Dr. Dakota McCoy, found that the feathers of species like the Superb Bird of Paradise absorb up to 99.95% of directly incident light.

That is Vantablack levels of dark.

By having these "super-black" feathers right next to vibrant blues or greens, the colors pop with an intensity that seems physically impossible. The black acts as a frame, making the colors look like they’re glowing. It’s a literal optical illusion built into their wings.

It's Not Just About the Looks

The dance is where it gets really intense. Most birds of paradise bird species don't just sit there and look pretty. They have "leks." These are essentially forest dance floors. The males will spend hours, sometimes days, clearing away every single leaf, twig, and piece of debris from their patch of ground. They want a clean stage.

If a female lands nearby, the performance starts.

- The Parotia does a "ballerina dance" where its feathers flare out into a tutu, and it shakes its head so fast its wires become a blur.

- The Superb Bird of Paradise snaps its wings to create a rhythmic clicking sound while bouncing in a circle.

- The Red Bird of Paradise hangs upside down and swings like a pendulum.

It’s high-stakes theater. If the male misses a step or a feather is out of place, the female just flies away. No second chances. This intense selective pressure is why we have such bizarre creatures today. If the females weren't so picky, these birds would probably just be boring brown things.

The Cultural Connection and the Dark History of Trade

We can't talk about these birds without acknowledging how they got their name. Back in the 16th century, the first skins reached Europe via Magellan’s circumnavigation. The skins had their legs and wings removed by local traders in the Maluku Islands.

The Europeans, being... well, Europeans at the time, decided this meant the birds had no legs and spent their entire lives floating in the air, fed by the dew of heaven. They thought the birds literally lived in paradise. Hence the name.

🔗 Read more: Bryant Park Bumper Cars: Why This NYC Winter Staple Is Worth the Chaos

While the "legless" myth died out, the demand for their feathers didn't. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of skins were exported to London and Paris for the millinery (hat-making) trade. It was a massacre. Thankfully, the practice was mostly banned by the 1920s, but it’s a reminder that our obsession with their beauty almost wiped them out.

Where Can You Actually See Them?

If you're thinking about seeing a birds of paradise bird in the wild, pack your bags for New Guinea. But be warned: it’s not a casual stroll. You’re looking at trekking through some of the most rugged, humid, and leech-infested terrain on the planet.

- The Arfak Mountains: This is the holy grail for birders. It’s where you’ll find the Western Parotia and the Flame Bowerbird (technically a cousin, but just as cool).

- Waigeo Island: This is where you go for the Wilson’s and the Red Bird of Paradise. The infrastructure is better here than in the highlands, but "better" is a relative term.

- Varirata National Park: Located near Port Moresby, this is one of the most accessible places to see the Raggiana Bird of Paradise, which is the national symbol of Papua New Guinea.

Most people opt for the documentaries, and honestly, I don't blame them. The cinematography in Our Planet or Planet Earth captures details you’d never see with the naked eye from 50 yards away in a dark rainforest.

The Conservation Reality

Is the birds of paradise bird endangered? It’s a mixed bag. Many species are doing okay because their habitat is so incredibly remote that logging companies haven't reached them yet. But as palm oil plantations expand and infrastructure creeps into the highlands, that’s changing.

Climate change is the silent killer here. These birds are often altitudinal specialists. They live in a very specific temperature band on a mountain. As the world warms, they have to move higher. Eventually, they’ll run out of mountain.

Groups like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the World Wildlife Fund are doing massive amounts of work to map these habitats. They aren't just counting birds; they're working with local indigenous communities. In many parts of PNG, the birds are sacred. Integrating traditional land ownership with conservation is the only way these species survive the next century.

How to Support and Learn More

If you want to actually do something rather than just read about them, here are the most effective moves you can make:

- Support the Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Their "Birds-of-Paradise Project" is the definitive scientific resource. They spent years capturing the first-ever footage of all 42 species. Donations go directly toward research and education.

- Check Your Wood and Oil: Habitat loss is driven by global demand. Look for FSC-certified wood products and RSPO-certified palm oil to ensure you aren't inadvertently funding the clearing of New Guinea's rainforests.

- Ethical Eco-Tourism: If you do travel to see them, hire local guides. When local communities see that a living bird is worth more in tourism dollars than a dead bird or a cleared forest, they become the fiercest protectors of the land.

- Use eBird: If you are a birdwatcher, log your sightings. Community science is a massive tool for researchers trying to track population shifts due to climate change.

The birds of paradise bird represents the absolute extreme of what nature can do when it’s allowed to get creative. They are a reminder that the world is still full of genuine, jaw-dropping mystery. Protecting that mystery isn't just about the birds; it's about keeping the planet's most vibrant colors from fading into the dark.