Software is changing. It's not just about buttons and menus anymore. We’re moving toward a world where code actually does things for you, rather than just waiting for you to click. But honestly? Most of the "agents" people are bragging about on LinkedIn right now are just fancy wrappers around a prompt. They break. They loop. They hallucinate. If you want to know how we build effective agents that actually survive a brush with the real world, you have to stop thinking about chatbots and start thinking about distributed systems.

It’s about reliability.

Think about the last time you tried to automate a task with an LLM. Maybe it worked once. Then, the next day, the model decided to output JSON in a slightly different format, or it got stuck in a "thought loop" where it just kept apologizing to itself. That’s the gap. Building effective agents requires a shift from "let's see what the AI says" to "how do we constrain this thing so it doesn't set the server on fire?"

The Architecture of Agency (It’s Not Just a Prompt)

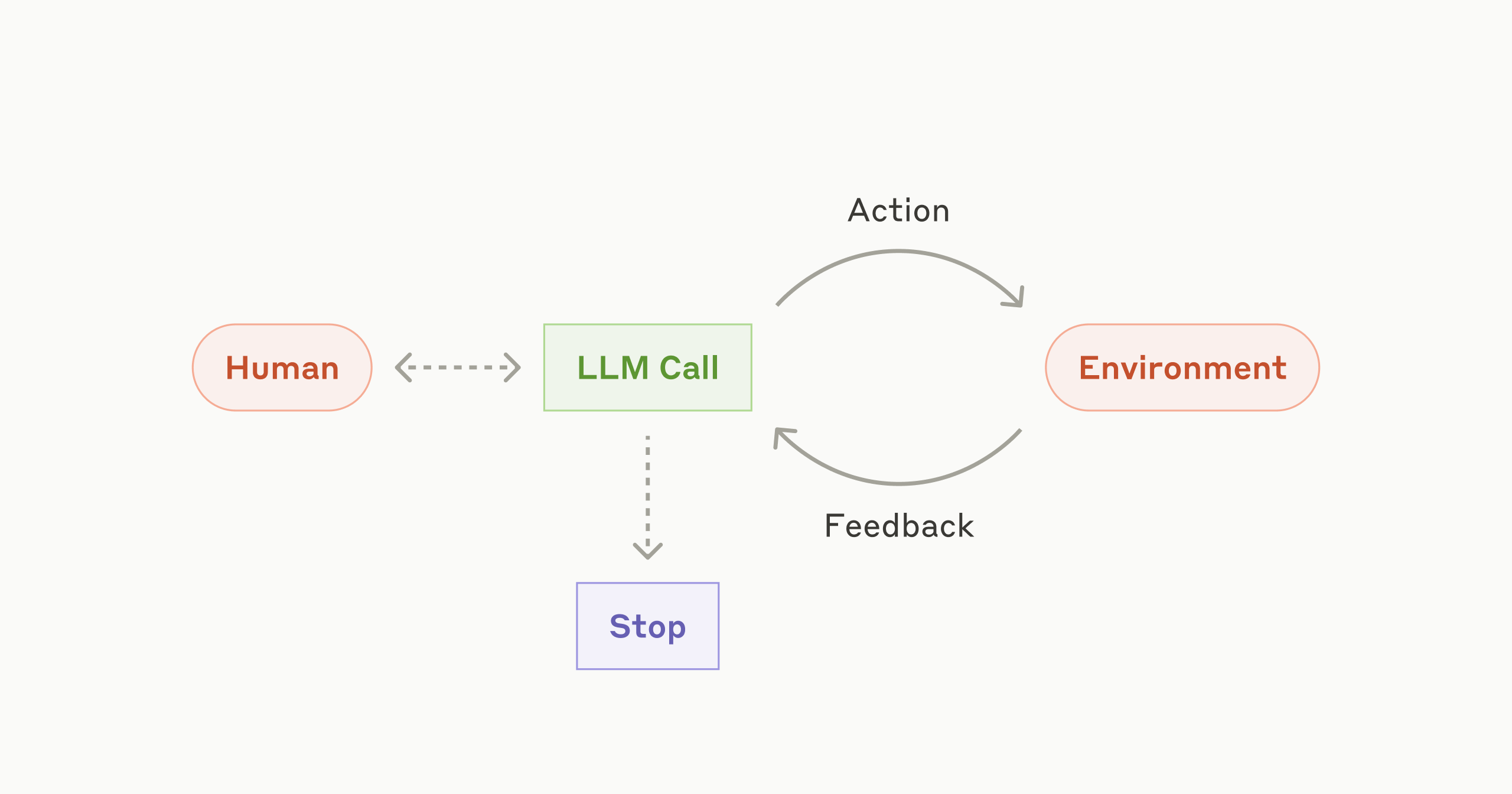

Most people think an agent is just an LLM with a "system prompt" telling it that it’s a world-class assistant. That’s a toy. Real agents—the kind being built by teams at OpenAI, Anthropic, or startups like Cognition—rely on a loop. This loop usually follows the ReAct pattern (Reasoning and Acting), popularized by researchers like Shunyu Yao.

The agent looks at a goal, thinks about what to do, takes an action, observes the result, and then repeats. Simple, right? Except it's not. The "Observation" part is where most systems fail. If the agent clicks a button and the page doesn't load, a bad agent just tries clicking again. An effective agent needs a "world model" to understand that the state has changed.

We have to build memory into these things. Not just a long list of previous messages, but structured memory. You’ve got short-term memory (the current conversation) and long-term memory (vector databases like Pinecone or Weaviate). But there’s a third type people forget: working memory. This is where the agent stores its current plan and its progress. Without a scratchpad, the agent loses the plot within three steps.

Why Tool Use is the Great Filter

You can't have an agent if it can't touch the world. This is "tool use" or "function calling."

When we talk about building effective agents, we’re talking about giving a model a hammer and making sure it doesn't hit its own thumb. The model needs to know when to use a tool and how to handle the error when that tool fails. For instance, if an agent is supposed to check a customer's order status in a SQL database, it shouldn't just write the query and hope for the best. It needs a sandboxed environment where it can test that query.

Security is a massive hurdle here. You don’t want an agent with "delete" permissions on your production database just because a user asked it to "clean things up." We use "human-in-the-loop" (HITL) checkpoints for high-stakes actions. It’s a bit of a buzzkill for total automation, but it’s the only way to sleep at night.

The Problem with Recursive Loops

Ever seen an AI talk to itself until it runs out of tokens? It’s painful. This happens because the agent lacks a "stop condition" or a way to recognize it’s not making progress.

To fix this, we implement "reflectors." This is a secondary LLM call—often using a smaller, faster model like GPT-4o-mini or Claude Haiku—that acts as a critic. It looks at the agent’s work and says, "Hey, you've tried the same API call four times and it’s still 404ing. Maybe try something else?" This multi-agent orchestration is becoming the gold standard. You have a "Manager" agent and a "Worker" agent. The Manager doesn't do the work; it just makes sure the Worker stays on track.

Evaluation is the Only Way Out

How do you know if your agent is actually better today than it was yesterday? You can't just "vibe check" it.

Building effective agents requires a rigorous evaluation pipeline, often called "Evals." Companies like Braintrust or LangSmith have built entire businesses around this. You need a dataset of 50 to 100 complex tasks with "golden" outputs. Every time you change a line of code or a prompt, you run the agent against those 100 tasks.

If your "success rate" drops from 80% to 75%, you revert. Even if the new prompt sounds "smarter" to you, the data doesn't lie. Nuance is everything here. Sometimes making a prompt more descriptive actually makes the agent perform worse because it gets "distracted" by the extra tokens—a phenomenon researchers call "lost in the middle."

Why Small Models are Winning the Agent War

There’s this misconception that you need the biggest, baddest model to build an agent. Honestly, that’s often wrong. Big models are slow. In an agentic loop where the model might need to "think" five times before giving an answer, a 10-second latency per call becomes a 50-second wait for the user. That’s unusable.

We’re seeing a shift toward "fine-tuned" smaller models. If you’re building an agent specifically for writing Python code, a fine-tuned Llama-3-70B might actually outperform a general-purpose GPT-4. It's faster, cheaper, and you can host it yourself, which solves a lot of the data privacy headaches that keep enterprise legal teams up at night.

The Reality of Prompt Engineering in 2026

Prompting isn't just "be a good bot" anymore. It's about "chain-of-thought" (CoT). You have to literally tell the model: "Think step-by-step. Write down your assumptions. Check your work."

But even better than CoT is "Few-Shot" prompting. Give the agent three examples of a successful task execution. Show it what a "bad" observation looks like and how to recover. This context is worth more than a thousand words of instruction.

It's also about what you don't say. Over-prompting leads to "instruction following fatigue." If you give an agent 50 rules, it'll follow the first five and the last five, and ignore the middle. Keep it lean. If a rule is really important, build it into the code as a hard constraint rather than a "pretty please" in the prompt.

Actionable Steps for Building Your First Real Agent

If you're ready to move past the "Hello World" of AI and build something that actually survives production, here is the path forward.

💡 You might also like: Why early 2000s mobile phones still feel more innovative than the iPhone 16

First, define the sandbox. Do not give your agent access to the open web or your whole database on day one. Use a tool like E2B or Fly.io to create a restricted environment where the agent can run code safely. If it crashes, it only crashes its own little bubble.

Second, implement a state machine. Don't let the LLM decide what the next "major" phase of the project is. Use code to define the states (e.g., "Researching," "Drafting," "Reviewing") and let the LLM operate within those states. This prevents the agent from wandering off into the woods.

Third, log everything. You need to see the "thought" process. If an agent fails, you should be able to replay that exact sequence of events to see where the logic diverged. Most people only log the final output, which is useless for debugging.

Finally, start with one tool. Just one. Make the agent perfect at using a Google Search tool or a Calculator tool before you give it a whole Swiss Army knife. Complexity is the silent killer of agents. Every tool you add increases the "search space" for errors.

The future isn't a single "God Model" doing everything. It's a swarm of small, specialized agents that know how to talk to each other and, more importantly, know when to stop and ask a human for help. That's how we build things that actually work.