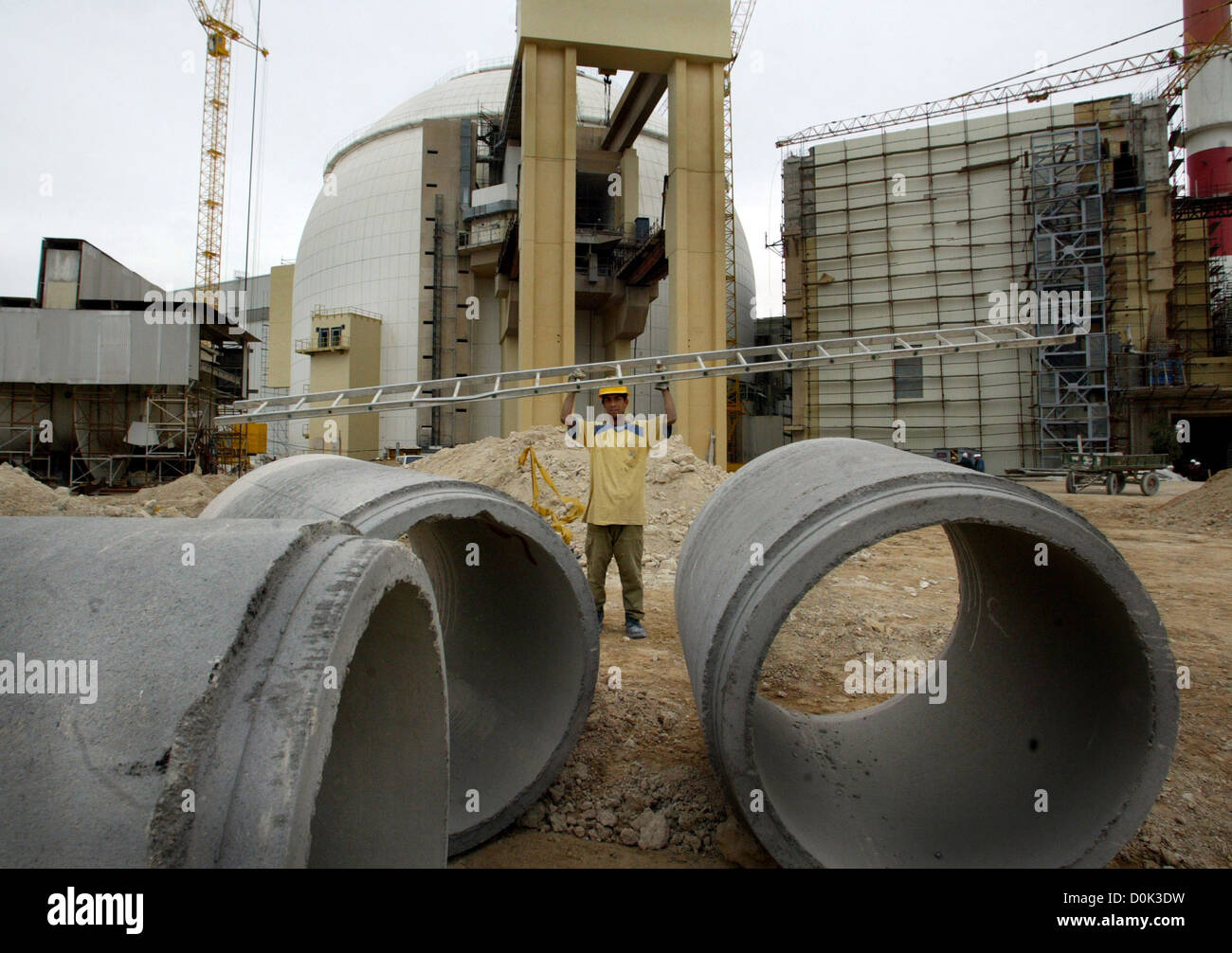

The Bushehr nuclear power plant is basically a massive architectural Frankenstein. Seriously. If you look at the history of global infrastructure, there aren’t many projects that have survived multiple revolutions, a full-scale war, and a complete change in technology partners. It sits right on the coast of the Persian Gulf, a sprawling complex that represents decades of geopolitical tug-of-war. For some, it’s a symbol of national pride and technological independence. For others, it’s a permanent fixture in international security debates.

Honestly, the story of Bushehr is wild. It didn't start with Russia, even though they’re the ones who finally got it online. It actually started with the Germans in the 1970s. Imagine trying to finish a puzzle where the pieces were designed by two different companies, thirty years apart, speaking different languages, using different units of measurement. That’s Bushehr in a nutshell.

How the Bushehr nuclear power plant became a geopolitical magnet

Back in 1975, the Shah of Iran had big dreams. He wanted a network of nuclear plants to power a modernizing nation. He tapped Kraftwerk Union AG, which was a joint venture of Siemens and AEG. They started building two units. Construction was humming along. Then, the 1979 Revolution happened. Everything stopped. The new government wasn't sure if they even wanted the plant anymore. Then Iraq invaded, and the site actually got hit by air strikes during the "War of the Cities."

By the time the dust settled in the late 1980s, the Germans were out. They couldn't come back even if they wanted to because of international pressure and sanctions. But the concrete shells were already there, baking in the sun. Iran needed a partner who would ignore the Western embargo. Enter Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear corporation.

The technical challenge was insane. The Russians had to take a German-designed containment building—built for a 1,300-megawatt Siemens pressurized water reactor—and somehow shove a Russian VVER-1000 reactor inside it. It’s like trying to put a Ferrari engine into a Porsche chassis, but the Porsche was built in 1974 and the engine was built in 2005. Engineers had to integrate thousands of tons of German equipment that was already installed with new Russian digital control systems.

💡 You might also like: How Much Is a Replacement AirPod: What the Apple Store Won't Mention Up Front

Breaking down the VVER-1000 technology

The core of the current facility is the VVER-1000/446. This is a third-generation pressurized water reactor. It uses four cooling loops. It's designed to be robust.

- The reactor pressure vessel is the heart, where the fission happens.

- The containment structure is double-walled, designed to withstand an earthquake of magnitude 8 on the Richter scale.

- It also features a "core catcher" in some of the newer units, though the first unit was a hybrid adaptation.

The plant finally reached full capacity in 2012. Think about that timeline. From the first shovel in the ground to full power took nearly four decades. Most tech is obsolete in five years; Bushehr is a monument to persistence, or maybe just sheer stubbornness.

The safety debate and the Persian Gulf environment

People worry about Bushehr. A lot. It’s not just the "nuclear" part that freaks neighbors out—it's the location. It sits near the junction of three tectonic plates. While the engineers swear the plant can handle a massive quake, folks in Kuwait and the UAE, which are just across the water, remain skeptical.

There's also the heat. The Persian Gulf is one of the warmest bodies of water on Earth. Nuclear plants need a lot of water for cooling. If the intake water is already 35°C (95°F), the efficiency of the cooling system changes. You've also got the issue of "red tide" or algae blooms that can clog up the intake pipes. In 2021, the plant had an emergency shutdown. The official word was a "technical fault," but rumors flew about everything from a generator failure to the aforementioned cooling issues.

Basically, running a high-output nuclear facility in a desert-marine environment is a constant battle against salt, heat, and seismic activity.

Why the fuel cycle matters here

The Bushehr nuclear power plant is unique because of how the fuel is handled. To ease international concerns about uranium enrichment, Russia agreed to provide the fuel and, crucially, take the spent fuel back. This "take-back" agreement is a big deal. It means Iran doesn't have to keep the highly radioactive waste on-site indefinitely, and it limits the risk of that waste being diverted for other purposes.

- Russia delivers the fuel rods.

- They stay in the reactor for about three years.

- They cool down in a pool.

- They go back to Russia for reprocessing or storage.

This setup is actually a model that some non-proliferation experts wish more countries would follow. It creates a closed loop that keeps the "scary stuff" under tight international supervision.

Looking ahead: Units 2 and 3

Iran isn't stopping with one reactor. They are currently working on Bushehr Phase II. This involves building two more Russian-designed reactors (VVER-1000s) right next to the first one.

Construction has been slow. Money is tight because of sanctions. Also, the COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench in the works back in 2020 and 2021. But the foundations are poured. You can see the progress on satellite imagery. This expansion is about more than just electricity. It’s about water. Iran is facing a massive water crisis. The plan is to use the heat from these new reactors to power massive desalination plants.

Imagine using nuclear energy to turn the salty Persian Gulf into drinking water for millions. That’s the "Lifestyle" side of this technological beast. If they pull it off, it changes the game for the southern provinces.

What most people get wrong about the site

A common myth is that Bushehr is a "bomb factory."

Technically, it's very hard to use a power reactor like this to make weapons-grade material. Light water reactors aren't ideal for that. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has cameras everywhere. They track every gram of fuel. Is it possible to hide things? In theory, sure, but Bushehr is probably the most scrutinized power plant on the planet.

Another misconception is that it's "Russian-run." While there are hundreds of Russian technicians on site, the ultimate goal of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) is to have Iranians running the show. They’ve been training staff for years at the Russian National Research Nuclear University (MEPhI).

Actionable insights for following the situation

If you're tracking the developments at the Bushehr nuclear power plant, you need to look past the headlines.

First, watch the IAEA quarterly reports. They provide the only objective data on fuel levels and inspections. Don't rely on "unnamed sources" in tabloid news.

Second, keep an eye on the regional "Green Middle East" initiatives. As countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE pivot toward their own nuclear programs (like the Barakah plant), the conversation around Bushehr might shift from "threat" to "regional safety standard."

Third, monitor the desalination progress. If Unit 2 comes online with a functional desalination hookup, it will prove that nuclear power in the Middle East is more about survival (water) than it is about just keeping the lights on.

Lastly, understand the economics. Nuclear power is expensive. With the rise of massive solar farms in the Iranian desert, the cost-benefit analysis of Bushehr is changing. The maintenance costs of a hybrid German-Russian plant are astronomical. The real story over the next decade isn't just "will it run," but "can they afford to keep it running?"

Keep your eyes on the seismic activity logs for the Bushehr province. Any quake above a 5.0 usually triggers a flurry of reports. Usually, the plant is fine, but the reaction from neighboring Gulf states will tell you more about the current political climate than any official press release from Tehran or Moscow.