You’ve probably heard that the Earth is a tiny blue marble in a vast, cold universe. But for a long time, the smartest people on the planet actually thought the stars were just like us. Not "like us" in a spiritual way—literally made of the same dirt, rocks, and iron we walk on every day.

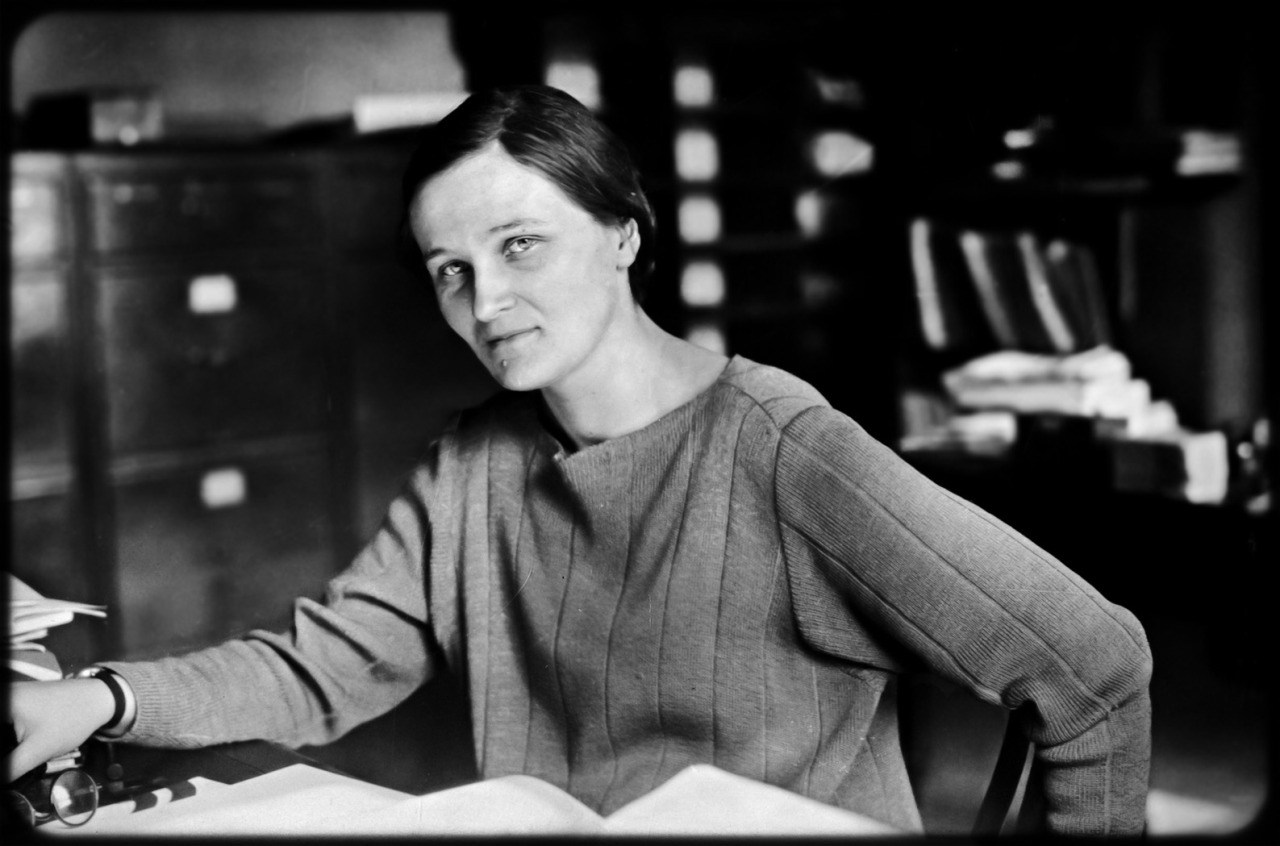

Then came Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin.

In 1925, she wrote a PhD thesis that basically told the entire scientific establishment they were wrong about everything. She proved that stars are almost entirely hydrogen and helium. It was the most brilliant dissertation ever written in astronomy, yet most people can't even pronounce her name.

The Girl Who Saw Through the Sun

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin didn't start out trying to upend the laws of physics. She was a botany student at Cambridge who happened to wander into a lecture by Arthur Eddington. He was talking about his trip to Africa to prove Einstein’s theory of relativity.

That one hour changed her life. Honestly, it changed the world.

She went home and realized she couldn't care less about plants anymore. She wanted the stars. But England in the 1920s wasn't exactly a playground for female scientists. Cambridge would let her take the classes, sure, but they wouldn't give her an actual degree.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Best TVs in Store at Walmart Without Getting Ripped Off

So, she packed her bags for America.

The Harvard Computers and the Big Lie

When she got to Harvard, she joined a group often called the "Harvard Computers." These were women who spent their lives squinting at glass plates—photographs of the sky—doing the math the men didn't want to do.

At the time, everyone believed "The Iron Sun" theory. They looked at the Sun's spectrum, saw lines for iron and calcium, and figured the Sun was just a hot version of Earth.

Cecilia wasn't buying it.

She used a brand-new piece of math called the Saha Ionization Equation. It’s a bit technical, but basically, she realized that just because you see a lot of iron lines in a star's light doesn't mean there's a lot of iron in the star. It just means iron is really good at showing up at that specific temperature.

When she ran the numbers for hydrogen, the result was insane.

Hydrogen wasn't just present. It was a million times more abundant than everything else.

"Clearly Impossible": The Man Who Blocked the Discovery

Here is where the story gets kinda frustrating. Cecilia sent her findings to Henry Norris Russell, the "Dean of American Astronomers" at the time.

He looked at her work and told her it was "clearly impossible."

💡 You might also like: Why the Designed by Apple in California Book is Still the Ultimate Flex for Tech Nerds

He didn't have math to back that up; he just had a gut feeling that the Earth and Sun must be the same. Because she was a 25-year-old grad student and he was the most powerful man in the field, she caved. She added a line to her thesis saying her results were "almost certainly not real."

Four years later? Russell did his own research, realized she was right, and published a paper reaching the same conclusion. He gave her a tiny shout-out, but he got the lion's share of the credit for decades.

Breaking the Glass Ceiling at Harvard

Cecilia’s life wasn't just about that one discovery, though. She stayed at Harvard for her entire career, even though the university treated her like a second-class citizen for most of it.

- She was the first person to get a PhD in astronomy from Harvard (technically Radcliffe, since Harvard didn't "do" female doctorates then).

- She spent years being paid out of the "equipment budget" because the university didn't have a job title for a female researcher.

- It took until 1956 for her to finally be named a full professor.

She eventually became the chair of the department. Think about that. She went from being a "manual laborer" of math to running the whole show.

What We Get Wrong About Cecilia Today

There’s a common narrative that she was a "hidden figure" who died in obscurity. That’s not quite true. By the end of her life, she was deeply respected. She won the Henry Norris Russell Prize—ironically named after the man who doubted her—and she saw her "impossible" theory become the bedrock of modern astrophysics.

👉 See also: Why All of Our Demise Is Actually About Physics (And What We Can Do)

We don't just use her discovery to know what stars are made of. We use it to understand how the universe began and where we come from. As Carl Sagan famously said, "We are made of starstuff."

Without Cecilia, we wouldn't have known what that "stuff" actually was.

How to Apply Her Legacy Today

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin didn't just discover hydrogen; she taught us how to be scientists. If you're looking for a takeaway from her life, here’s how to channel that "Gaposchkin energy":

- Trust the data over the "experts." If your numbers are right but the person in charge says they're wrong, look for the flaw in their logic, not just yours.

- Persistence is a skill. She waited 31 years for a title she earned in her twenties. She didn't quit; she just kept doing the work.

- Cross-pollinate your ideas. She didn't just use astronomy; she brought in the latest chemistry and physics (Saha's theory) to solve a problem that had stumped everyone for a century.

If you ever find yourself looking at a problem that everyone says is "impossible," remember Cecilia. She looked at the brightest thing in the sky and saw what everyone else was missing because she was the only one brave enough to believe the math.

To dive deeper into the actual physics she used, you can look up the Saha-Boltzmann equation or read her autobiography, The Dyer's Hand. It's a raw look at what it was like to be the smartest person in a room that didn't want you there.