Most people think they know classic solitaire card games because they spent the late nineties procrastinating in a cubicle. You remember the green felt background. The pixelated cards. That frantic, satisfying cascade of decks bouncing across the screen when you finally cleared the board. It felt like a triumph over the machine. But there is a weird, deep history to these games that has nothing to do with Microsoft or 1990. In fact, if you’re still calling it "Solitaire" as if it’s just one thing, you’re missing out on a massive world of strategy that’s kept people sane for centuries.

Solitaire is actually an umbrella.

It covers everything from the relaxing "Klondike"—the one you know—to the absolutely brutal "Canfield," which was originally designed in a Saratoga Springs gambling joint to make sure players lost their shirts. The name itself comes from the French word for patience. It makes sense. If you’ve ever sat through a deck that just won't give you a red seven, you know exactly how much patience is required.

The Accidental Empire of Klondike

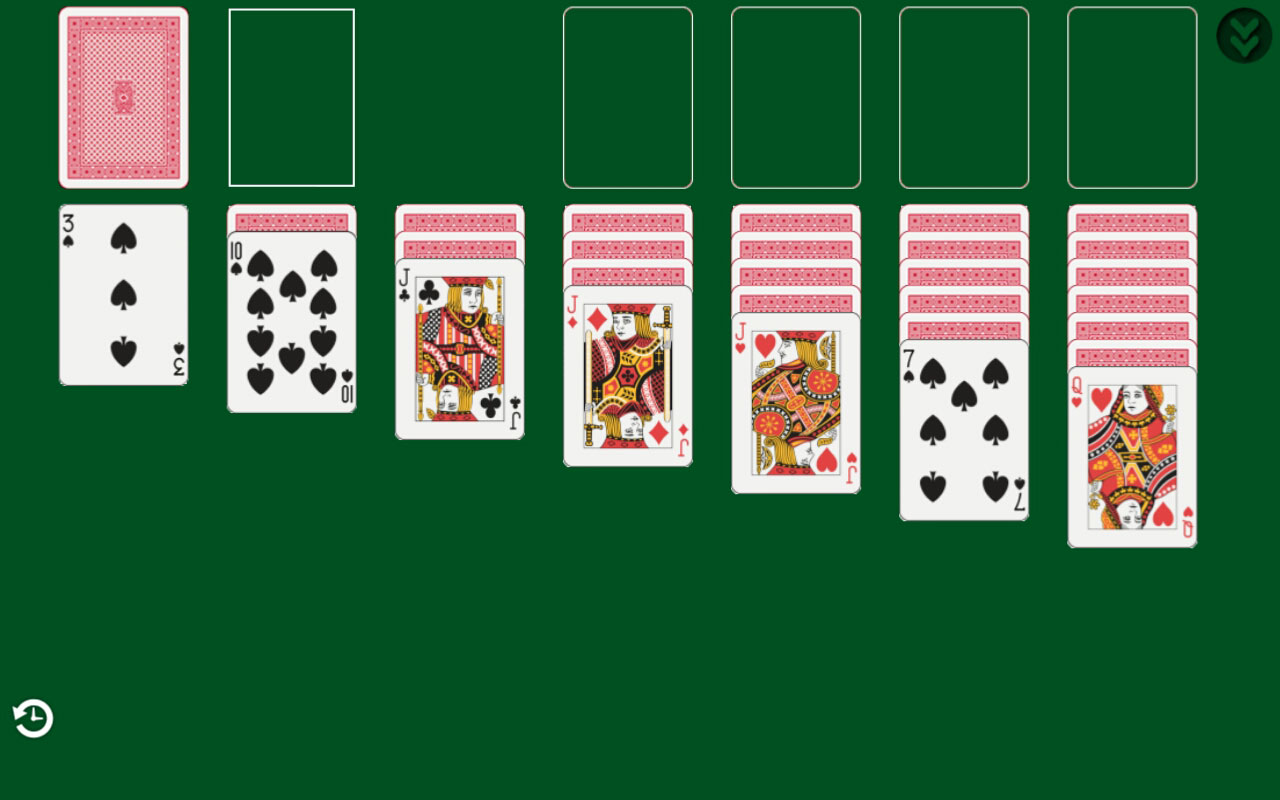

When people search for classic solitaire card games, they’re almost always looking for Klondike. It’s the gold standard. It’s named after the Klondike Gold Rush, which tells you everything you need to know about its vibes: high stakes, solitary, and a little bit desperate. You’ve got your seven columns. You’ve got your stockpile. You’re just trying to get everything into those four foundation piles by suit.

But why did this specific version win?

In 1988, an intern at Microsoft named Wes Cherry wrote the code for the version we all know. He didn't even get royalties for it. Think about that. One of the most-played pieces of software in human history was written by an intern who was just bored. Microsoft included it in Windows 3.0 not because they wanted to revolutionize gaming, but because they needed a sneaky way to teach people how to use a mouse. Seriously. In 1990, the concept of "drag and drop" was alien to most folks. Moving a king to an empty space was a literal training exercise.

The game became a phenomenon because it filled the "micro-breaks" of our lives. You can finish a hand in three minutes. Or you can get stuck for twenty. It’s a perfect loop of frustration and dopamine.

Beyond the Basics: Spider, FreeCell, and the Real Skill Gap

If Klondike is the entry drug, FreeCell is the hard stuff for people who hate luck. Most classic solitaire card games rely on a "shuffle of the draw." If the cards are buried wrong, you lose. It doesn't matter if you're a genius. FreeCell changed that.

Developed by Paul Alfillé, FreeCell is almost entirely merit-based. Out of the millions of possible deals, only a handful are actually unsolvable. When you lose at FreeCell, it’s usually your fault. That realization is either addictive or infuriating. You have four "open cells" that act as temporary storage. It’s like a sliding tile puzzle mixed with a card game.

Then there’s Spider Solitaire.

If you want to feel like your brain is being stretched, play a four-suit game of Spider. It uses two decks. It’s messy. It’s sprawling. While Klondike feels like tidying a room, Spider feels like organizing a warehouse during an earthquake. You’re building sequences in descending order, but you can only move groups if they’re the same suit. It requires a level of look-ahead thinking that makes it feel more like chess than a casual hobby.

Why Your Brain Craves the Sort

There is actual science behind why we do this. Dr. Thomas Zimmer, a researcher who has looked into the psychology of "patience" games, suggests that these games provide a "flow state" that’s uniquely accessible. You aren't competing against a 13-year-old in a different country who is screaming into a headset. You’re just sorting chaos into order.

In a world that feels increasingly chaotic, there is a profound, almost meditative comfort in seeing a shuffled deck become four neat piles. It’s low-stakes control.

The Darker Roots: Gambling and Canfield

We shouldn't pretend this was always a wholesome pastime for bored office workers. Take Canfield Solitaire. It was named after Richard Canfield, a casino owner in the 19th century. He’d sell you a deck for $50 and pay you $5 for every card you played to the foundation. To break even, you had to play ten cards.

Most people didn't.

Canfield is notoriously difficult. The deck is stacked against you—literally. It uses a "reserve" pile of 13 cards, and only the top one is visible. It’s a game of narrow margins and tight corners. When you play it today on your phone, you’re playing a game that was designed to take people's money. That’s why it feels so much tighter and more punishing than the breezy Klondike.

Real Strategy: Stop Playing the First Card You See

If you want to actually win at classic solitaire card games, you have to stop playing on autopilot. Most people see a move and make it instantly. That’s a mistake.

Here is the professional way to look at a board:

- Prioritize the Large Piles: In Klondike, the goal isn't just to move cards to the top. It’s to flip the hidden cards in the columns. If you have a choice between moving a card from the stockpile or moving a card from a 6-card deep column, you pick the column every single time.

- The King Vacuum: Don't empty a spot unless you actually have a King ready to move into it. An empty spot is a tool. If you vacate it too early, you just lost a column of maneuverability.

- The Foundation Trap: Sometimes, moving a card to the foundation pile (the Aces at the top) too early can screw you over. You might need that 5 of Hearts to hold a 4 of Spades later. If the 5 is already "home," you’re stuck.

What Most People Get Wrong About Winning

There’s a myth that every game is winnable. It isn't.

In standard Klondike (Draw 3), the win rate for a skilled player is somewhere around 10% to 15% if you play strictly by the rules without "undo" buttons. If you’re playing Draw 1, that jumps up significantly, but it’s still not 100%. Accepting the "loss" is part of the game’s philosophy. It’s a simulation of life: sometimes the deck is just against you, and the skill lies in recognizing when you’ve done the best you could with a bad hand.

The Digital Evolution

We’ve moved far beyond the basic green-screen Windows 95 version. Today, you have "Solitaire Royale," "Fairway Solitaire" (which mixes it with golf mechanics), and even "Ziggurat" styles. But the core mechanics—the stacking, the suit-matching, the descending order—haven't changed since the 1700s when the first references to these games appeared in German texts.

📖 Related: Why How to Make a Sofa on Minecraft is Still the Best Way to Level Up Your Interior Design

Even the deck designs have stories. The "Bicycle" brand we all know became the standard because of its durability. During wars, "patience" games were often the only thing keeping soldiers from losing their minds in trenches or barracks. It’s a portable, silent companion.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Player

If you're looking to dive back into classic solitaire card games, don't just settle for whatever bloatware is on your computer.

- Try "Golf" or "Tri-Peaks" for speed: These are much faster and rely on "value plus or minus one" logic rather than suit-stacking. They are great for high-score chasing.

- Switch to "Vegas Scoring": Most apps have this setting. It mimics the old Canfield casino rules. It makes every move feel more consequential because you're "buying" the deck.

- Use a Physical Deck: Seriously. There is a tactile satisfaction in shuffling and dealing a real deck of cards that a touch screen cannot replicate. It also forces you to learn the rules properly because there’s no "illegal move" warning to stop you.

- Check out the "World Solitaire Championship" layouts: If you think you're good, look up professional layouts used in competitive speed-runs. It will humble you very quickly.

Solitaire isn't just a way to kill time. It's a mental gym. Whether you're trying to beat a personal best in FreeCell or just trying to survive a brutal hand of Canfield, you're engaging with a tradition of logic that spans centuries. Next time you open that app, remember you aren't just clicking cards; you're solving a mathematical puzzle that has stumped kings and commoners alike.