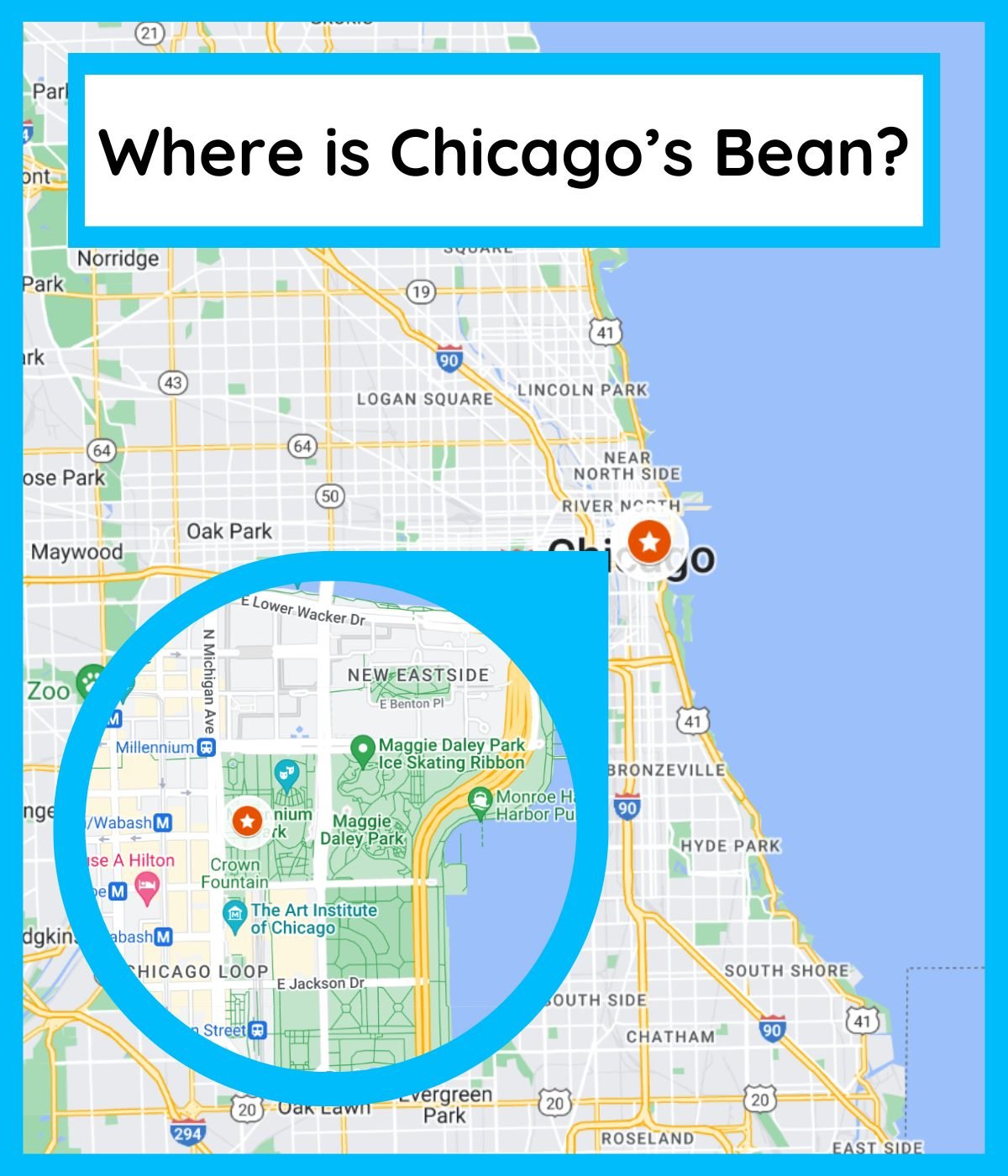

You’ve seen the selfies. You’ve probably seen the distorted skyline reflecting off that giant, silver legume in the middle of Millennium Park. But honestly, most people standing in front of it have no clue what they’re actually looking at. They call it "The Bean," though the artist, Anish Kapoor, famously hated that nickname at first. He officially titled it Cloud Gate.

If you walk up to it and rap your knuckles against the side, it feels solid. Dense. It doesn’t ring like a bell, yet it looks like a liquid drop of mercury that just happened to freeze in the Chicago wind. So, what is the Chicago Bean made of? The short answer is stainless steel. The long answer is a feat of 21st-century engineering that almost didn't happen because it was considered "impossible" to build.

The Skeleton Under the Skin

Most people think it’s a solid chunk of metal. It isn't. If it were solid steel, it would weigh enough to collapse the underground parking garage it sits on. Instead, it’s a hollow shell supported by a complex internal framework.

Think of it like a giant, metallic ribcage.

The structure inside is made of two massive steel rings. These rings are connected by a truss system—basically a web of steel beams—that keeps the whole thing from sagging. This "skeleton" is what allows the sculpture to expand and contract. Because Chicago is, well, Chicago, the temperature swings are brutal. We’re talking about 100°F in the summer and -20°F in the winter. Without a flexible internal structure, the steel skin would buckle or crack within a single season.

✨ Don't miss: 去洛杉矶郡艺术博物馆 LACMA 拍照之前,有些事你真的得先搞清楚

Kapoor worked with a firm called Performance Structures, Inc. (PSI) out of Oakland, California. They were chosen because they had experience making high-precision hulls for boats and research submarines. If you can make a submarine that survives the crushing pressure of the ocean, you can probably make a big metal bean for the Midwest.

The Magic of 316L Stainless Steel

The "skin" of the sculpture is the star of the show. It’s made of Type 316L stainless steel.

Why that specific grade? Because 316L contains molybdenum. That’s a chemical element that makes the steel incredibly resistant to corrosion. In a city where road salt is sprayed everywhere for six months a year and the air is humid from Lake Michigan, regular steel would turn into a rusty mess in no time. 316L keeps it bright.

There are 168 individual plates of this steel covering the exterior. Each plate was roughly 10 millimeters thick—which is about 3/8 of an inch. That’s surprisingly thin when you think about the scale of the thing. These plates weren't just flat sheets; they were precision-milled using massive rollers and heat to get those specific, mind-bending curves.

The Invisible Seams

This is where the engineering gets borderline obsessive. When the plates arrived in Chicago, they were welded together. If you look at it today, you can't see a single weld. Not one.

The workers used a process called "stitch welding." They’d weld a small section, let it cool, then weld another. Once the structure was fully assembled, a team of specialized polishers spent months—literally months—grinding down the seams. They used increasingly fine abrasives, starting with rough grits and ending with polishing compounds that are basically a paste.

The goal was to make the 168 plates look like a single, seamless drop of liquid. It’s a trick of the eye. The seams are still there, they’ve just been polished to a point where the crystalline structure of the metal is uniform across the entire surface.

Dealing with the Chicago Elements

The Bean is basically a giant mirror. Mirrors get dirty.

Every single day, the lower portion of the sculpture (the part humans can reach) is wiped down to remove fingerprints, grease, and whatever else tourists leave behind. But twice a year, it gets a "deep clean." Workers use about 40 gallons of liquid detergent to wash the whole thing. They don't use high-pressure power washers because they don't want to risk pitting the surface. It’s all very delicate for something that weighs 110 tons.

Then there’s the heat. In the dead of summer, the steel can get hot enough to actually burn you if you lean against it for too long. Conversely, in the winter, the interior is sometimes heated to prevent ice from forming in a way that could stress the welds. It’s a living, breathing piece of architecture.

The Numbers That Matter

- Total Weight: 110 tons (roughly the weight of two or three adult blue whales).

- Dimensions: 33 feet high, 42 feet wide, and 66 feet long.

- Cost: Originally budgeted at $6 million, it ended up costing around $23 million. Private donors covered the tab, thankfully.

- The "Omphalos": That’s the fancy word for the 12-foot-high arch underneath. It’s Greek for "navel." When you stand under it, the reflections multiply into infinity.

Why Stainless Steel Was the Only Choice

Kapoor had a vision of "extraordinary perfection." He wanted something that would disappear into the sky while simultaneously pulling the ground up toward the viewer.

Glass was too fragile for a public park. Aluminum was too soft and wouldn't hold that mirror finish for decades. Chromium plating would have peeled over time. Stainless steel—specifically the high-nickel, low-carbon 316L—was the only material that could survive the public while providing the optical clarity needed for the reflection.

It’s interesting to note that the sculpture isn't actually attached to the ground in a traditional sense. It sits on the plaza, but the internal "feet" are designed to slide slightly. This accounts for the thermal expansion we talked about earlier. If it were bolted down rigidly, the stress of a Chicago "Polar Vortex" would tear the metal apart.

Seeing it for Yourself

If you're planning a visit, don't just look at the outside. Walk into the center. Look up into the "Omphalos." The way the steel is curved there is even more complex than the outer shell. It’s designed to warp your perception of space.

Also, a bit of insider advice: go at sunrise. The way the 316L steel catches the orange light reflecting off the skyscrapers to the west is something you can't capture on a smartphone at noon. The metal loses its clinical, silver look and glows like it’s actually molten.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Visit

- Check the Maintenance Schedule: The Bean occasionally undergoes major "facelifts" where it’s fenced off for polishing. Check the Millennium Park official site before traveling.

- Look for the Seams: See if you can find them. (Spoiler: You can’t, but it’s fun to try).

- Touch the Surface: It’s allowed! Just be aware that in August, that steel is a heat sink.

- Observe the Reflection: The sculpture is designed so that the top half reflects the sky and the bottom half reflects the city. It’s a literal bridge—a "gate"—between the two.

The Chicago Bean is a testament to what happens when art pushes technology to its absolute limit. It isn't just a big shiny rock; it’s 110 tons of marine-grade steel, precision-engineered to make the city of Chicago look like a dream.

👉 See also: Why Every Boutique Hotel Williamsburg NYC Actually Offers Feels Different

Next Steps for the Curious Traveler

If you're fascinated by the engineering of Cloud Gate, you should head over to the Art Institute of Chicago nearby. They often have exhibits detailing the urban planning of Millennium Park. Additionally, researching the "Chicago Picasso" in Daley Plaza offers a great comparison of how different metals—in that case, Cor-Ten steel—age over time in the same climate. Unlike the Bean, the Picasso is designed to rust into a deep brown patina, proving there's more than one way to build a masterpiece in the Windy City.