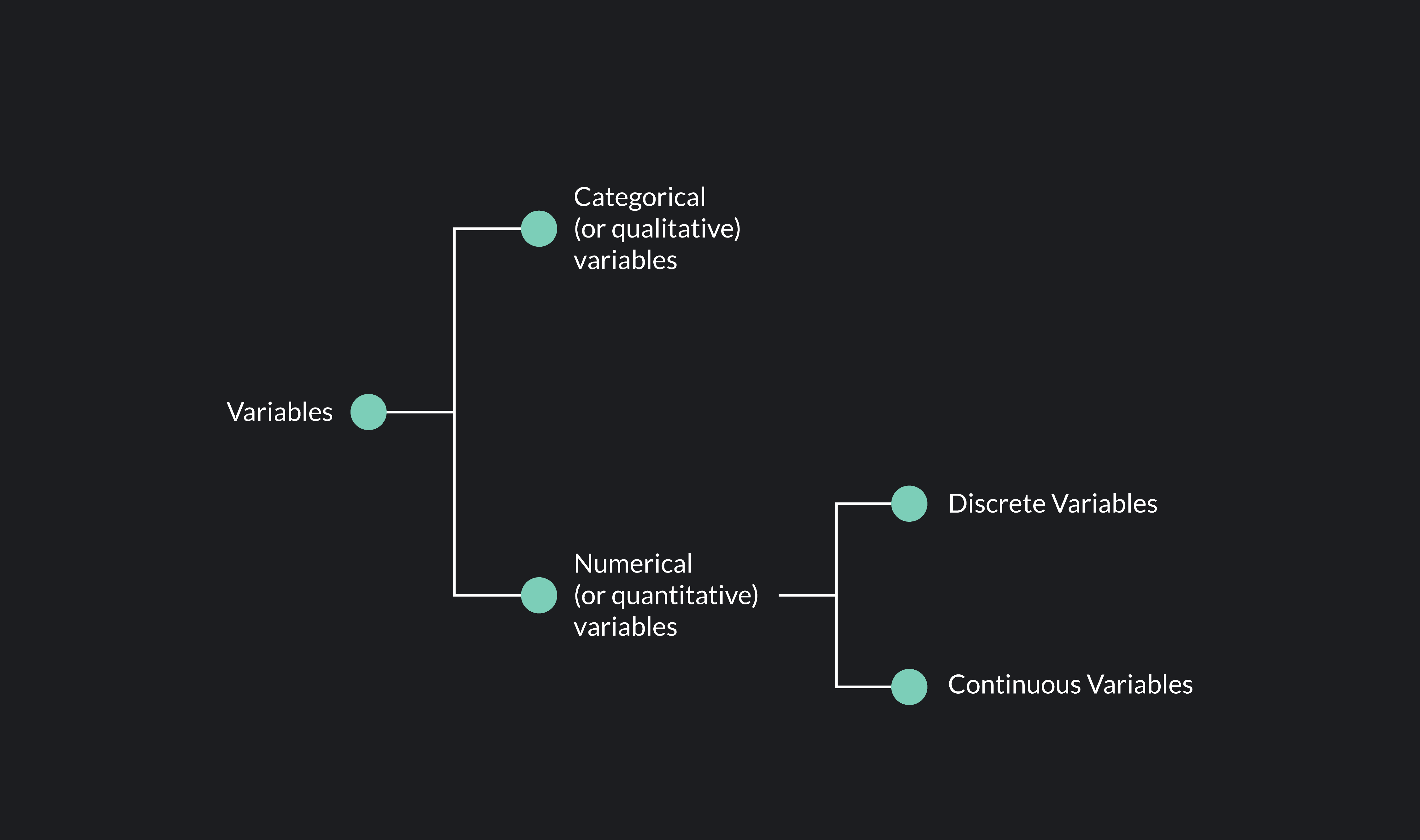

Data is messy. Honestly, most people treat it like a giant bucket of numbers without realizing that the type of number dictates every single thing you can do with it later. If you're building a machine learning model or just trying to pass a stats exam, you’ve gotta nail the difference between continuous variables and discrete variables. It sounds academic. It’s not. It’s the difference between measuring how much water is in a glass and counting how many glasses are on the table. One can be broken down into infinite tiny pieces; the other is stuck in rigid, whole-number chunks.

Get this wrong? Your charts look like garbage. Your p-values lie to you. Your "predictive" model starts predicting that a family will have 2.48 children, which—last I checked—is a biological impossibility and a bit of a horror movie plot.

👉 See also: Why Your Living Room Needs a 75 inch smart tv lg Right Now

The Rigid World of Discrete Variables

Discrete variables are the "counters." They are distinct. Separate. They have gaps between them. Think about the last time you bought a pack of eggs. You bought 6, or 12, or maybe 18. You didn't buy 12.439 eggs. The universe of eggs in a carton is discrete.

You'll often hear people say these are "whole numbers," and while that's usually true, it's not a hard rule. The defining trait is that you can't find another value between two points if the scale doesn't allow it. If you're counting the number of "likes" on a social media post, you go from 10 to 11. There is no 10.5. It's a jump. A leap.

Why money is a weird edge case

Here is where it gets kinda tricky. Money. Is money a discrete or continuous variable? Most textbooks will tell you it's discrete because you can't go smaller than a cent (or whatever the smallest unit of your currency is). You can't have $10.0054 in your physical wallet. However, in high-frequency trading or complex financial modeling, analysts often treat it as continuous because the scale is so massive and the increments so small that the "gaps" don't really matter for the math to work. It’s a nuance that trips up students all the time. But for most of us? If you can count it on your fingers (even if you need a lot of fingers), it's discrete.

- Number of cars in a parking lot.

- How many times you’ve checked your phone today.

- The number of players on a soccer pitch.

- Your shoe size (it’s either a 9 or a 9.5; you can't get a 9.27).

The Infinite Slide of Continuous Variables

Now, flip the script. Continuous variables are the "measurers." They don't jump; they flow. Think about height. You aren't just 5 feet or 6 feet. You are 5.78432... feet tall, depending on how expensive your ruler is. Between any two points on a continuous scale, there is an infinite number of other possible values.

That's the kicker: infinity.

If you're measuring the time it takes for a website to load, it could be 2 seconds. Or 2.1 seconds. Or 2.100005 seconds. The only limit is the precision of your instrument. This is why things like weight, temperature, and distance are the poster children for continuous data. They exist on a spectrum.

The Precision Trap

We often treat continuous variables like discrete ones just to make life easier. You might say you're 30 years old. That sounds discrete, right? A nice, whole number. But age is actually time, and time is continuous. You are actually 30 years, 4 days, 2 hours, 10 minutes, and 6 seconds old. As I typed that, you got older. It's a constant stream. In data science, knowing when to treat "age" as a continuous number (to see fine-grained trends) versus a discrete "bucket" (like 18-25, 26-35) is a massive part of the job.

Why the Distinction Actually Matters for Your Bottom Line

If you use the wrong statistical test, your results are basically fiction. You can't use a T-test on certain types of discrete data without things getting weird.

For continuous variables, we use things like probability density functions. Since there are infinite possible values, the probability of any exact value (like being exactly 175.0000000cm tall) is technically zero. We instead measure the chance of someone falling within a range.

For discrete variables, we use probability mass functions. We can actually say there is a 20% chance of a household having exactly 2 pets.

Data Visualization Blunders

Ever seen a line graph showing the number of people who visited a museum each day? If the line is smooth, it's technically implying that at 2:30 PM, there were 40.5 people in the building. That's a bit macabre. For discrete data, bar charts are your best friend because they respect the gaps between the bars. The gaps say, "Nothing exists here." For continuous data, histograms or scatter plots show the flow and the density of the information.

The Gray Areas: When Data Blurs

Real-world data isn't always as clean as a Pearson textbook. Let’s talk about "Ordinal Data." If I ask you to rate your pain on a scale of 1 to 10, is that discrete or continuous?

🔗 Read more: Dead Pixels on iPad Pro: What Most People Get Wrong About Screen Defects

Technically, it's discrete. You pick a 7 or an 8. But many researchers treat it as continuous because it represents an underlying "continuum" of pain. This is a huge point of contention in psychology and social sciences. If you treat a 1-10 scale as continuous, you can calculate a mean (the average pain is 6.4). If you treat it as discrete, you really should be looking at the mode (the most common answer was 7).

Using the wrong approach can lead to "over-precision." Just because your calculator says the average happiness of your employees is 7.42 doesn't mean that ".42" actually represents anything in the physical world.

Mathematical Foundations: A Quick Look

If you want to get technical—and we should, briefly—continuous variables can be represented by the formula for a line or a curve where $f(x)$ is defined for every $x$ in an interval. Discrete variables are often represented by summations.

$$P(X = x) = f(x)$$

In the discrete world, you sum up the probabilities of individual outcomes. In the continuous world, you integrate over an interval to find the area under the curve. If that sounds like high school calculus coming back to haunt you, you’re right. But it's the reason your GPS can calculate your exact arrival time while your bus pass only counts the number of rides you have left.

Practical Steps for Handling Your Data

Don't just start clicking buttons in Excel or R. Stop. Look at your variables.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Trying to Steal a Brainrot Script Right Now

First, ask yourself: "Can I divide this in half and have it still make sense?" If you divide a "number of children" variable in half, you get a mess. If you divide "time spent on a task" in half, you just get a smaller unit of time.

Second, check your "N." If you have a discrete variable with hundreds of possible whole-number outcomes (like the number of calories in a meal), you might be better off treating it as continuous for the sake of your model. If you have a continuous variable that only has a few likely outcomes, maybe bin it into categories.

Third, choose your visuals based on the "gap." No gaps? Use a histogram. Gaps? Use a bar chart. It sounds simple, but you’d be surprised how many "experts" at Fortune 500 companies get this wrong in their quarterly slide decks.

Finally, remember that the tool must fit the data, not the other way around. Whether you're tracking heart rates (continuous) or heart attacks (discrete), the math you choose will dictate whether your insights are actionable or just noise.

Start by auditing your current spreadsheets. Label your columns as 'D' or 'C'. You’ll find that just this one step clears up about 50% of the confusion in your analysis. If you're using Python, check your dtypes. If a discrete variable is being read as a float, or a continuous one as an object, your entire analysis is already skewed. Fix the types, fix the model.