Computers are actually kinda dumb. Honestly, they are just a massive collection of tiny switches that can either be "on" or "off." That is it. While we humans walk around using ten fingers to count—which is why we use the denary system (base-10)—computers don't have that luxury. They operate in a world of binary (base-2). If you’ve ever wondered how your laptop turns a photo of a cat or a complex spreadsheet into a string of electricity, it all starts with the math of converting denary to binary.

Most people think this is some high-level wizardry reserved for MIT grads. It isn't. It’s basically just division and subtraction. If you can count to ten, you can learn to speak the language of silicon.

The "Remainder" Shortcut Everyone Uses

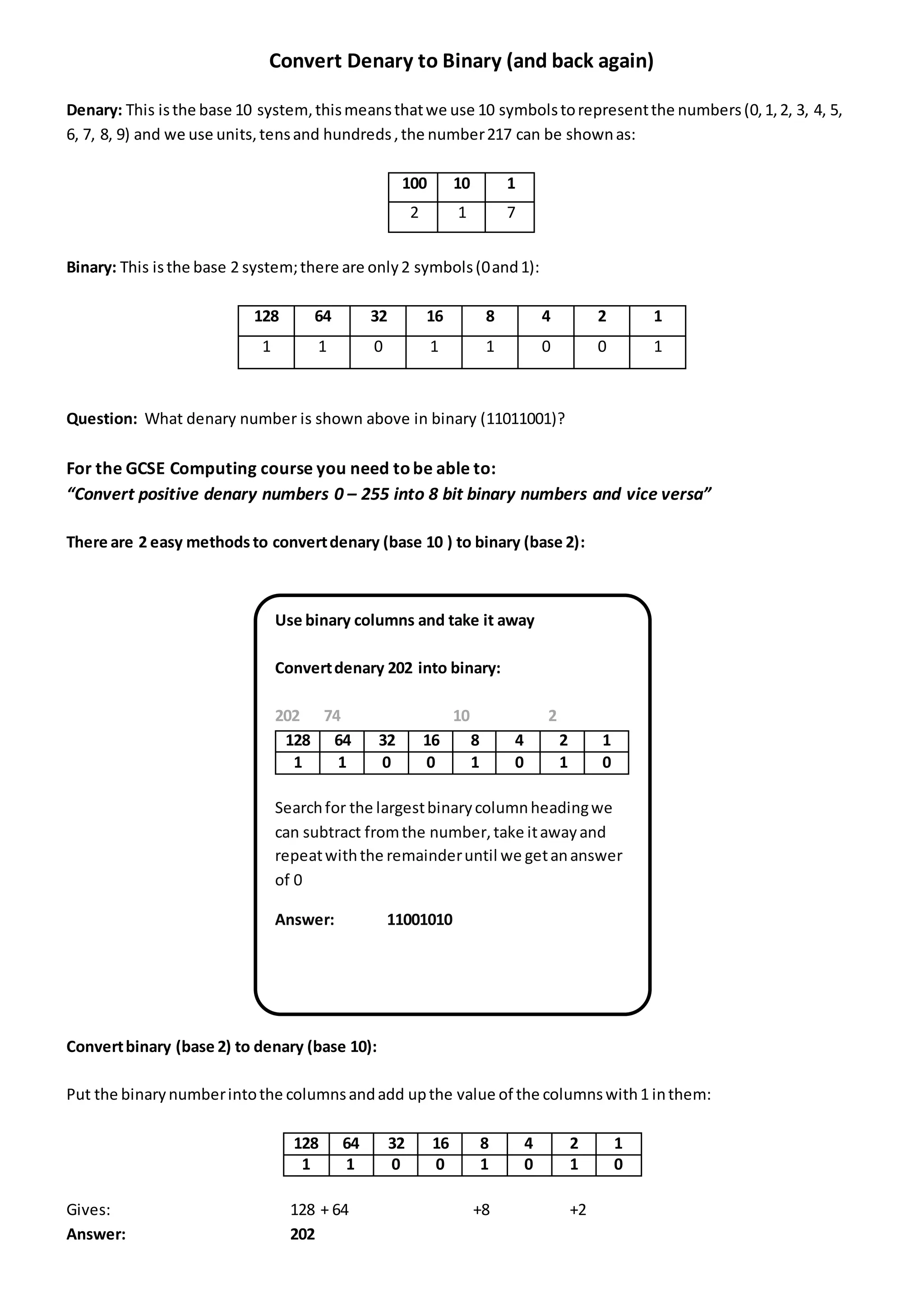

There are two main ways to do this. The first is the "Successive Division by 2" method. It’s the most reliable way to handle large numbers without getting a massive headache. You basically take your denary number, keep dividing it by two, and keep track of the remainders.

Let's look at the number 13.

First, you divide 13 by 2. You get 6 with a remainder of 1. Write that 1 down on the right side. Now, take that 6 and divide it by 2. You get 3 with a remainder of 0. Next, divide 3 by 2. You get 1 with a remainder of 1. Finally, divide 1 by 2. You get 0 with a remainder of 1.

When you read those remainders from the bottom up, you get 1101. That is 13 in binary. Simple, right?

Why Do We Even Call it Denary?

Some people call it decimal. Others call it denary. In the UK and many computer science circles, "denary" is the preferred term to avoid confusion with "decimal points." The word comes from the Latin denarius, meaning "containing ten." We use it because we have ten fingers. It’s an evolutionary quirk. If we had evolved with eight fingers, we’d probably all be using octal, and the world would look very different.

Binary, on the other hand, comes from the Latin binarius, meaning "consisting of two." In a circuit, you either have voltage or you don’t. There is no "sorta on." This is why binary is the foundation of every digital device you've ever touched. From the original ENIAC computer to the smartphone in your pocket, the logic remains identical.

The Subtraction Method: For the Mentally Quick

If you don't like dividing, you can use the "Descending Powers of Two" method. This is how most programmers do it in their heads for smaller numbers. You just need to know your powers of two: 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

Suppose you want to convert the number 45.

✨ Don't miss: Walkie Talkies: Why They Actually Work Better Than Your iPhone in the Real World

- Does 128 fit into 45? No. (0)

- Does 64 fit? No. (0)

- Does 32 fit? Yes. (1) Now subtract 32 from 45. You have 13 left.

- Does 16 fit into 13? No. (0)

- Does 8 fit into 13? Yes. (1) Subtract 8. You have 5 left.

- Does 4 fit into 5? Yes. (1) Subtract 4. You have 1 left.

- Does 2 fit into 1? No. (0)

- Does 1 fit into 1? Yes. (1)

Line up those 1s and 0s: 00101101. In an 8-bit system (a byte), that’s your answer.

Where People Usually Mess Up

The biggest mistake is the "Bottom-Up" rule. When using the division method, beginners almost always write the binary string in the wrong order. They write it from the first remainder to the last. This is wrong. The first remainder you calculate is actually the Least Significant Bit (LSB), which goes on the far right. The last one is the Most Significant Bit (MSB), which goes on the left.

Another common pitfall is forgetting the zeros. In binary, a zero is a placeholder, just like in denary. If you mean 101, you can't just write 11 because you "didn't feel like" writing the zero. That changes the value from 5 to 3. Precision matters.

Why You Should Care in 2026

You might think, "Why do I need to know how to convert denary to binary when my calculator does it for me?" Well, understanding this logic is the key to understanding how data compression works. Ever wonder how a 4K movie fits onto a disc? It's all about manipulating these bits.

Network engineers use this constantly for Subnet Masking. When you look at an IP address like 192.168.1.1, that’s just a human-friendly way of writing four sets of 8-bit binary numbers. If you want to secure a network or set up a router manually, you've got to understand how those bits translate.

Advanced Perspective: Signed Integers and Two's Complement

Life gets messy when you introduce negative numbers. In denary, we just slap a minus sign on it. Computers can't do that. They use something called Two's Complement. To represent -5, they don't just put a minus sign. They take the binary for 5 (0101), flip all the bits (1010), and then add 1 (1011).

It sounds needlessly complicated, but it allows the computer's hardware to perform subtraction using the same circuits it uses for addition. It’s an elegant solution to a hardware limitation.

Practical Steps to Master Binary Conversion

To get good at this, you have to stop thinking in tens. Start by memorizing the powers of two up to 256. It takes ten minutes. Once you have those numbers—2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256—burnt into your brain, the subtraction method becomes second nature.

📖 Related: Disk Drill Data Recovery: What Most People Get Wrong About Saving Their Files

- Practice with your age. If you’re 25, that’s 16 + 8 + 1, so 11001.

- Try converting your house number.

- Use a "Binary Clock" app to force your brain to read time in base-2.

Once you can look at the number 172 and instantly see 10101100, you’ve officially bridged the gap between human thought and machine logic. This isn't just a math trick; it's the fundamental architecture of the digital age.

Next Steps:

Go find a sheet of paper. Don't use a screen. Pick three random numbers between 1 and 100. Convert them using both the division method and the subtraction method to see which one "clicks" for your brain. If they don't match, you've found a logic error—debug it. That’s the first step to thinking like a programmer.