You’re looking at a photo of a dog. Within milliseconds, your brain registers the floppy ears, the wet nose, and the golden fur. You don't think about it. You just know it’s a Golden Retriever. But for a computer, that same convolutional neural network image is just a massive, terrifying grid of numbers. We're talking millions of pixels, each assigned a value for red, green, and blue. Making sense of that chaos is arguably the greatest achievement of modern AI, yet most people have no idea how messy the process actually is.

It’s not magic. It’s math. Specifically, it’s a lot of matrix multiplication that mimics—roughly—how the visual cortex in a human brain functions.

How a Convolutional Neural Network Image Actually "Sees"

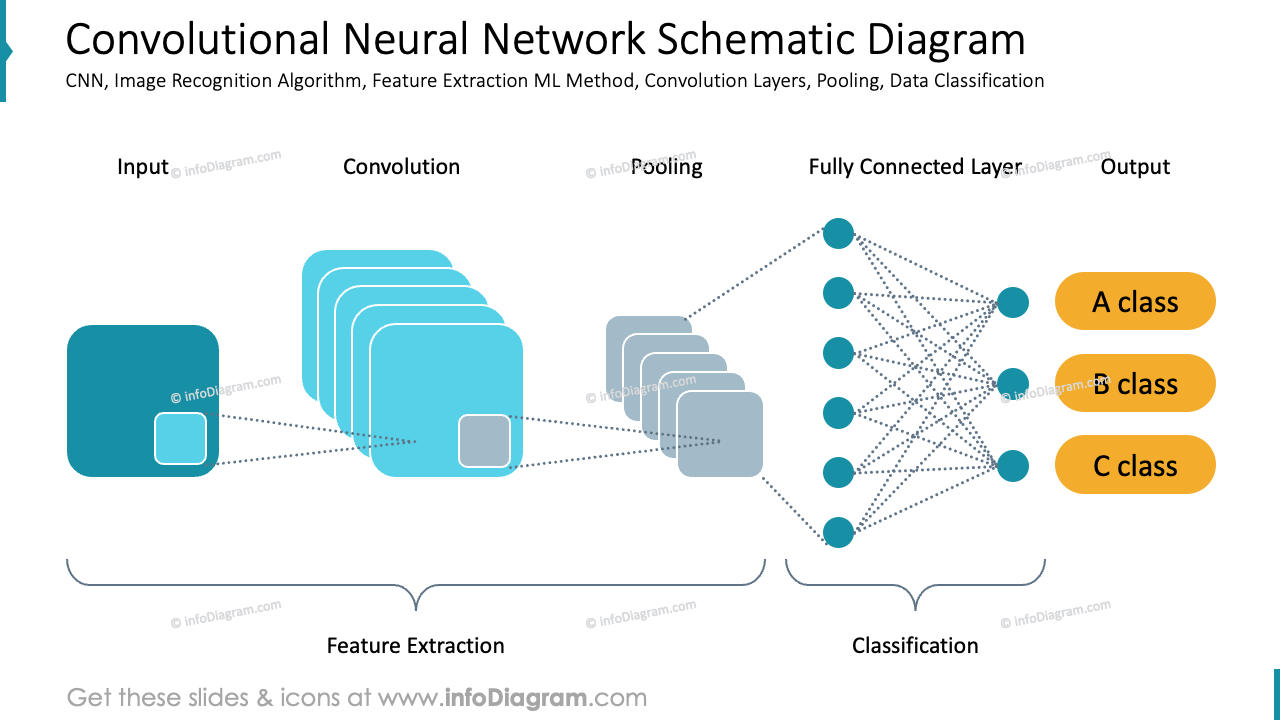

When we talk about a CNN (Convolutional Neural Network), we’re talking about a specific architecture designed to process data that has a grid-like topology. Images are the perfect candidate. Traditional neural networks fail miserably here because they try to learn global patterns all at once. If you move a cat two pixels to the left in a standard feed-forward network, the "math" breaks. The computer thinks it's looking at a completely different object.

CNNs fixed this by using something called "spatial invariance."

Basically, the network uses filters. Think of a filter as a tiny magnifying glass that slides across the image. This "sliding" is the convolution. These filters aren't looking for a "dog" right away. That’s a common misconception. In the first few layers, the network is incredibly dumb. It’s looking for edges. Vertical lines. Horizontal gradients. Maybe a specific shade of neon pink.

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Class Action: What Really Happened with the $20 Million Settlement

As the convolutional neural network image data moves deeper into the architecture, these simple edges get combined. Two edges become a corner. Corners become circles. Circles become an eye. It’s a hierarchy of features. Yann LeCun, often called the "Father of the Convolutional Net," pioneered this with LeNet-5 back in the 90s to recognize handwritten ZIP codes. It was slow. It was clunky. But it proved that machines could learn visual hierarchies without a human explicitly telling them what a "seven" looks like.

The Kernel is the Secret Sauce

If you’ve ever used a sharpen filter in Photoshop, you’ve used a convolution. A kernel is a small matrix—usually $3 \times 3$ or $5 \times 5$—that performs a mathematical operation on a neighborhood of pixels.

- Input: A grid of pixel values.

- Operation: The kernel slides (convolves) over the input.

- Output: A "feature map" that highlights specific traits.

If the kernel is designed to find vertical lines, the resulting feature map will be bright where there are vertical lines and dark everywhere else. In the early days, engineers hand-coded these kernels. Now? The network learns them through backpropagation. It fails, it gets corrected, it tweaks the numbers in the kernel, and it tries again. Millions of times.

Why We Keep Getting Convolutional Neural Network Image Results Wrong

There’s a massive problem called "adversarial attacks" that proves CNNs don't actually "see" like we do.

Researchers at MIT and other institutions have shown that if you change just a few pixels in a convolutional neural network image—changes invisible to the human eye—you can trick a world-class AI into thinking a school bus is an ostrich. This happens because the AI is hyper-fixated on textures and statistical patterns rather than "objectness."

We see a bus. The CNN sees a specific frequency of yellow and black pixels distributed in a way that its training data once associated with an ostrich. It’s a sobering reminder that while these networks are powerful, they are essentially high-dimensional pattern matchers, not conscious observers. They lack "common sense."

The Layers Nobody Explains Well

Most tech blogs just say "it has layers." That’s lazy. You need to understand three specific parts:

- Convolutional Layers: These do the heavy lifting of feature extraction.

- Pooling Layers: This is essentially downsampling. It shrinks the image to make the computation faster and to make the detection more robust to small shifts. If a cat's ear moves slightly, Max Pooling ensures the network still catches it.

- Fully Connected Layers: This happens at the very end. Once the features are extracted, they are flattened into a long list and fed into a standard neural network to make the final "That's a cat" or "That's a dog" prediction.

Real-World Impact: Beyond Just Labeling Cats

We use this tech every day. It’s in your pocket.

✨ Don't miss: Ukraine Fiber Optic Field: How a Resilient Network Actually Works Under Pressure

When you search your Google Photos for "beach," a CNN is scanning your library. In healthcare, companies like Zebra Medical Vision use convolutional neural network image analysis to spot microscopic hemorrhages in CT scans that a tired radiologist might miss at 3:00 AM. This isn't about replacing doctors; it's about providing a "second set of eyes" that never gets bored and never needs coffee.

In autonomous driving, companies like Tesla and Waymo rely on CNNs to segment the road. The car has to know what is "road," what is "sidewalk," and what is "human child chasing a ball." The latency has to be near zero. If the network takes too long to convolve the pixels, the car crashes. This is why specialized hardware, like NVIDIA's GPUs and Google’s TPUs, are so vital. They are built specifically to do the type of math—parallel matrix multiplication—that CNNs require.

The Problem of Data Bias

If you train a convolutional neural network image model only on photos of white people, it will struggle to recognize or classify people of color. This isn't a theory; it’s a documented failure in facial recognition software used by law enforcement. The "ImageNet" dataset, which fueled the AI explosion in 2012, has historically been skewed toward Western contexts.

If a network sees 10,000 "weddings" where everyone is wearing white dresses, it might not recognize a traditional Hindu wedding as a wedding. We have to be incredibly careful about the "ground truth" we feed these machines. Garbage in, garbage out. It’s a cliché because it’s true.

Practical Steps for Building Your Own Image Classifier

You don't need a PhD to play with this. Honestly. You just need a bit of Python and a lot of patience.

- Start with Transfer Learning: Don't try to train a CNN from scratch. You don't have the compute power or the data. Use a pre-trained model like ResNet-50 or VGG16. These have already "learned" how to see edges and shapes from millions of images. You just need to "fine-tune" the very last layer to recognize your specific objects.

- Data Augmentation is Mandatory: If you only have 100 photos of your product, turn them into 1,000. Flip them. Rotate them. Change the brightness. This forces the convolutional neural network image to learn the actual shape rather than just memorizing a specific photo.

- Check Your Saliency Maps: Use tools like Grad-CAM to see where the network is looking. If you’re building a model to detect skin cancer and the saliency map shows it’s looking at a ruler the doctor held next to the mole, your model is useless. It’s learning the "ruler" means "cancer," not the mole itself.

- Normalize Your Inputs: Always scale your pixel values. Instead of 0-255, scale them to be between 0 and 1 or -1 and 1. It makes the math significantly more stable and prevents "exploding gradients" which can kill your training process instantly.

Moving Forward

The next frontier isn't just seeing images; it’s understanding them. We're moving toward Vision Transformers (ViTs), which treat images more like sequences of words. They handle long-range dependencies better than standard CNNs. While CNNs are still the king of the convolutional neural network image world due to their efficiency, the lines are blurring.

If you’re a developer or a business owner, stop looking for "perfect" accuracy. It doesn't exist. Focus on "robustness." A model that is 90% accurate but works in rain, snow, and low light is far more valuable than a 99% accurate model that only works in a studio. The real world is messy, and your data should be too.

Start by auditing your training set. Look for the gaps. Look for where the model fails. That’s where the real learning happens—for both you and the machine.