You’ve probably been there. You type a date into a cell, try to subtract it from another, and suddenly Excel spits out a random five-digit number like 45291. It feels like the software is gaslighting you. Honestly, understanding how to handle a date in excel formula isn't about memorizing a hundred different functions; it's about realizing that Excel doesn't actually see dates as dates. It sees them as a timeline of serial numbers starting from the beginning of the 20th century.

If you can wrap your head around that one weird quirk, you've basically mastered half the battle.

Most people treat Excel like a typewriter. They type "January 1st" and wonder why their math fails later. But Excel is a calculator first. Every single date you enter is just a hidden number representing the days elapsed since January 1, 1900. If you type $1$ and format it as a date, you get January 1, 1900. If you type $45291$, you get January 1, 2024. This is the foundation of every calculation you’ll ever run.

The DATE Function is Your Best Friend

Forget typing dates manually inside formulas. If you write something like ="12/25/2023" - "12/20/2023", you’re begging for a "Value" error depending on whether your computer thinks you’re in the US or the UK. It’s messy. Instead, use the DATE function. It’s the only way to be 100% sure Excel knows exactly what day you’re talking about, regardless of regional settings.

The syntax is straightforward: DATE(year, month, day).

Why does this matter? Because years, months, and days are often stored in different columns in real-world data. Maybe you’re pulling a "Year" from a dropdown and a "Month" from a text string. You use DATE(A2, B2, C2) to stitch them back together into a real, clickable, calculable piece of data. It’s clean. It works.

When Things Go Sideways: The "Text" Trap

One of the biggest headaches I see experts deal with is the "Date-as-Text" nightmare. This usually happens when you export data from a CRM or accounting software. The date looks right. It says 2024-05-15. But Excel is treating it like a word, not a number. You try to sum it or find an average, and nothing happens.

You can check this easily. If the "date" is aligned to the left of the cell, Excel thinks it's text. If it’s on the right, it’s a number. To fix this within a date in excel formula, you can often use the DATEVALUE function. It’s a specialized tool that forces Excel to look at a text string and translate it back into that serial number we talked about earlier.

Sometimes, even that fails. If your data is truly garbage, you might need to use LEFT, MID, and RIGHT to manually carve out the year, month, and day before shoving them back into a DATE function. It's tedious work, but it's the only way to get clean results for a pivot table or a complex dashboard.

Calculating Differences Without Losing Your Mind

If you need to know how many days are between two dates, just subtract them. It’s literally =End_Date - Start_Date. Simple. But what if you only want workdays? This is where NETWORKDAYS comes in.

Most people forget that NETWORKDAYS has a secret third argument: holidays. You can create a small list of dates off to the side, name it "MyHolidays," and include it in your formula: =NETWORKDAYS(A2, B2, MyHolidays). Now your project timeline doesn't accidentally assume people are working on Christmas or New Year's Day.

The Weird Case of DATEDIF

Then there’s DATEDIF. This is a "ghost" function. You won't find it in the formula autocomplete list in Excel because it’s actually a legacy function kept around for compatibility with Lotus 1-2-3. Despite being a bit of a relic, it’s incredibly useful for calculating age or tenure in specific units like "years" or "months."

To use it, you type =DATEDIF(start_date, end_date, "y") for years. Change that "y" to "m" for months or "d" for days. Just be careful with the "md" argument (days between dates as if they were in the same month)—Microsoft has actually acknowledged it can produce inaccurate results in certain scenarios. Use it sparingly.

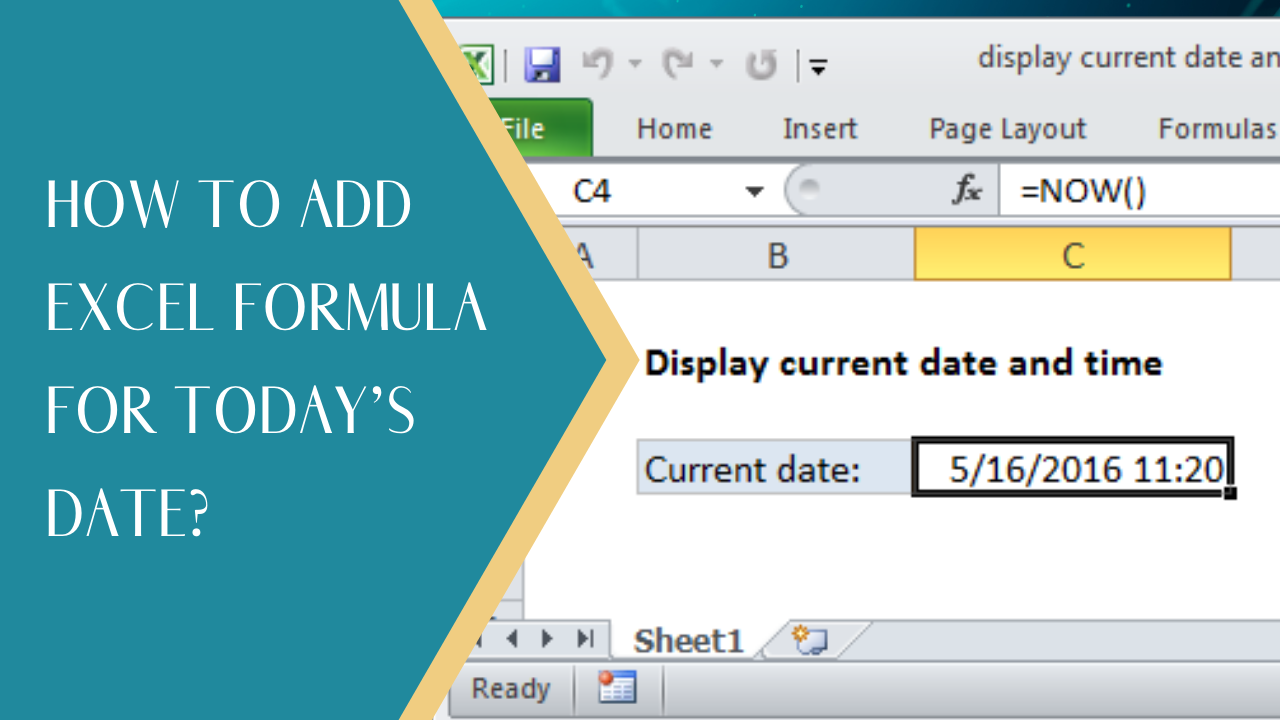

Dynamic Dates and Today’s Moving Target

A lot of people use the TODAY() function to make their reports dynamic. It's great. Every time you open the file, the date updates. But there is a massive catch. TODAY() is a "volatile" function. This means every single time you change anything in your spreadsheet—even if it's unrelated—Excel recalculates every formula containing TODAY().

In a small sheet, who cares? In a massive workbook with 50,000 rows? You’ll feel the lag. It’ll start to crawl.

💡 You might also like: Weather Radar Pueblo CO: Why the High Plains Are So Hard to Predict

If you need a timestamp that stays put, don't use a formula. Use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + ; (semicolon). That hard-codes the current date into the cell so it won’t change tomorrow. It’s a small trick, but it saves hours of frustration when you're trying to track when a task was actually completed versus what day it is now.

Formatting Isn't Data

This is the hill I will die on: the way a date looks has nothing to do with what the date is. You can format a cell to show "Wednesday" or "15-May" or "05/15/24." To Excel, it’s still just 45427.

The TEXT function is how you bridge this gap in a formula. If you want to create a sentence that says "The report is due on Wednesday," you can't just concatenate a date cell with text. It’ll look like "The report is due on 45427." Instead, use = "The report is due on " & TEXT(A2, "dddd").

That "dddd" tells Excel to display the full name of the day. Using "mmm" gives you the short month name, and "yyyy" gives you the year. It gives you total control over how the date in excel formula outputs information to your end-user.

Logic and Comparisons

Dates work perfectly with logical operators like >, <, and =. This is huge for conditional formatting or IF statements.

Imagine you’re tracking invoices. You want to know if a payment is overdue. You’d write something like =IF(A2 < TODAY(), "OVERDUE", "OK"). Because dates are just numbers, "less than" effectively means "earlier than." It's intuitive once you stop thinking about the month names and start thinking about the timeline.

Troubleshooting the #VALUE! Error

If your formula is breaking, check your separators. Some countries use dots, some use slashes, some use dashes. If you’re collaborating with someone in another country, their Excel might be looking for DD/MM/YYYY while yours expects MM/DD/YYYY.

This is exactly why the DATE function is safer than typing dates in quotes. DATE(2026, 1, 17) is universal. It doesn't matter if you're in New York or London; Excel knows exactly which year, month, and day you mean.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Year 2000 Issues: Believe it or not, Excel still has rules for two-digit years. If you type "30," Excel assumes 1930. If you type "29," it assumes 2029. Just use four digits. Always.

- The 1900 Leap Year Bug: Excel actually thinks 1900 was a leap year (it wasn't). This was a deliberate mistake by the original developers to maintain compatibility with Lotus 1-2-3. It rarely affects modern calculations unless you're doing historical research, but it's a fun bit of trivia.

- Time is a Fraction: If you see a date like

45427.5, that.5is noon. Time is just a decimal of a day. If your date formulas are acting weird, check if there’s a hidden time component messing up your "equals" comparisons.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit Your Exports: Next time you download a report, use the

ISNUMBERfunction on a date cell. If it returnsFALSE, your dates are actually text and will break your formulas. - Standardize with DATE(): Stop typing

"1/1/2026"inside yourIForSUMIFSformulas. Swap them out forDATE(2026, 1, 1). - Master the Shortcut: Practice using

Ctrl + ;for static timestamps to avoid the performance heavy-lifting of volatile functions likeTODAY(). - Clean Up Displays: Use the

TEXTfunction to make your automated summaries readable for people who don't want to see raw date formats.

Understanding dates in Excel is less about math and more about understanding the "under-the-hood" numbering system. Once you stop fighting the serial numbers and start using them, your spreadsheets become much more robust and way less likely to break when you share them with someone else.