You’re standing on the ground. It feels solid. But really, you’re being relentlessly tugged toward the center of a giant, spinning ball of rock by an invisible thread. We call it gravity. Most of us just think of it as "down," but if you're trying to launch a satellite or just wondering why you weigh more in certain parts of the world, you need the earth gravitational force formula. It’s not just some dusty math from a textbook. It is the literal law that keeps the moon from flying off into the void and ensures your coffee stays in the mug.

People often get confused between the general rule for gravity and the specific way we calculate it here on Earth. Honestly, it’s understandable. Physics has a way of making simple things sound like a foreign language. But once you peel back the layers, it's basically just a story of mass and distance.

🔗 Read more: Why You Should Buy Apple AirPods Pro 2 Before the Next Generation Drops

What is the Earth gravitational force formula anyway?

When we talk about the force between the Earth and an object on its surface, we’re usually looking at Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. Sir Isaac Newton realized that every single thing in the universe with mass is pulling on every other thing.

The formula looks like this:

$$F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$$

In this equation, $F$ is the force of gravity. $G$ is the gravitational constant—a tiny, tiny number that stays the same everywhere. Then you have $m_1$ (the mass of the Earth) and $m_2$ (the mass of you, or your car, or a sandwich). Finally, $r$ is the distance between the centers of those two masses.

Why the distance matters so much

Notice that $r$ is squared. This is huge. It’s called the inverse-square law. If you double the distance between two objects, the gravity doesn't just drop by half; it drops to one-fourth. This is why astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) feel "weightless," even though Earth’s gravity is still pulling on them with about 90% of the strength we feel on the ground. They are just far enough away—and moving fast enough sideways—to stay in a constant state of freefall.

The shortcut we use every day

Unless you are a literal rocket scientist at NASA or SpaceX, you probably don't use that big formula very often. Instead, we use a simplified version. Because the Earth’s mass ($M_E$) and its radius ($R_E$) are mostly constant, we can squish them together with $G$ to get a single number.

That number is $g$, or $9.8$ $m/s^2$.

So, for most Earth-bound problems, the earth gravitational force formula becomes:

$$F = mg$$

It's simple. It’s elegant. It’s why you can calculate the weight of a 10kg bowling ball in your head ($98$ Newtons). But here’s the thing: that $9.8$ number is a bit of a lie.

Earth isn't a perfect ball

If the Earth were a perfect, smooth sphere of uniform density, gravity would be the same everywhere. It isn’t. Our planet is actually an "oblate spheroid." It’s fat at the equator and squashed at the poles because of its rotation.

Because you are physically closer to the center of the Earth when you stand at the North Pole than when you stand in Ecuador, you actually weigh more at the poles. It’s not much—maybe about 0.5%—but if you’re shipping thousands of tons of gold, that 0.5% matters. Geophysicists use tools like the GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) satellites to map these "gravity anomalies." There are spots in the Indian Ocean where gravity is weirdly low, and places like the Andes mountains where it's higher because of the extra mass of the rock.

The Role of G (The Big Constant)

The $G$ in our formula is $6.674 \times 10^{-11}$ $Nm^2/kg^2$. This number is incredibly small. It’s why you don’t feel a gravitational pull toward your refrigerator or your best friend. You need a massive amount of matter—like a planet—before gravity becomes something you can actually feel.

Henry Cavendish was the first person to actually "weigh the Earth" by measuring this constant in 1798. He used a torsion balance, which is basically a stick hanging from a wire with lead balls on the ends. By watching how much the wire twisted when other lead weights were brought close, he calculated the density of the Earth. It’s wild to think that we figured this out over 200 years ago using some wire and some lead.

Misconceptions about falling objects

You’ve probably heard the story about Galileo dropping two balls of different masses from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Whether he actually did it or not is debated, but the physics is sound.

Looking back at $F = mg$, you might think a heavier object falls faster because the force $F$ is greater. And you’d be right about the force. A bowling ball is pulled harder than a feather. But—and this is the "aha!" moment—the bowling ball also has more inertia. It’s harder to get moving. These two things cancel out perfectly.

In a vacuum, where there is no air resistance, everything falls at the exact same rate. This was famously proven on the Moon during the Apollo 15 mission when Commander David Scott dropped a hammer and a feather at the same time. They hit the lunar dust simultaneously. On Earth, air ruins the experiment, but the earth gravitational force formula still dictates the underlying pull.

How this affects modern technology

We don't just use these formulas for physics homework. They are the backbone of modern life.

- GPS Satellites: Your phone knows where you are because satellites are orbiting the Earth. To stay in a specific orbit, their velocity must perfectly balance the gravitational pull calculated by our formula. If they go too slow, they crash. Too fast, they fly into deep space.

- Tide Predictions: The moon’s gravity pulls on Earth’s oceans. By using the same formula (but swapping Earth’s mass for the Moon’s), we can predict high and low tides with incredible precision.

- Climate Science: Changes in Earth's gravity can actually tell us if ice sheets are melting. As ice turns to water and flows into the ocean, the mass of that region decreases, and the local gravity changes slightly. Satellites pick this up, giving us a "weight-based" view of climate change.

Nuance: General Relativity vs. Newton

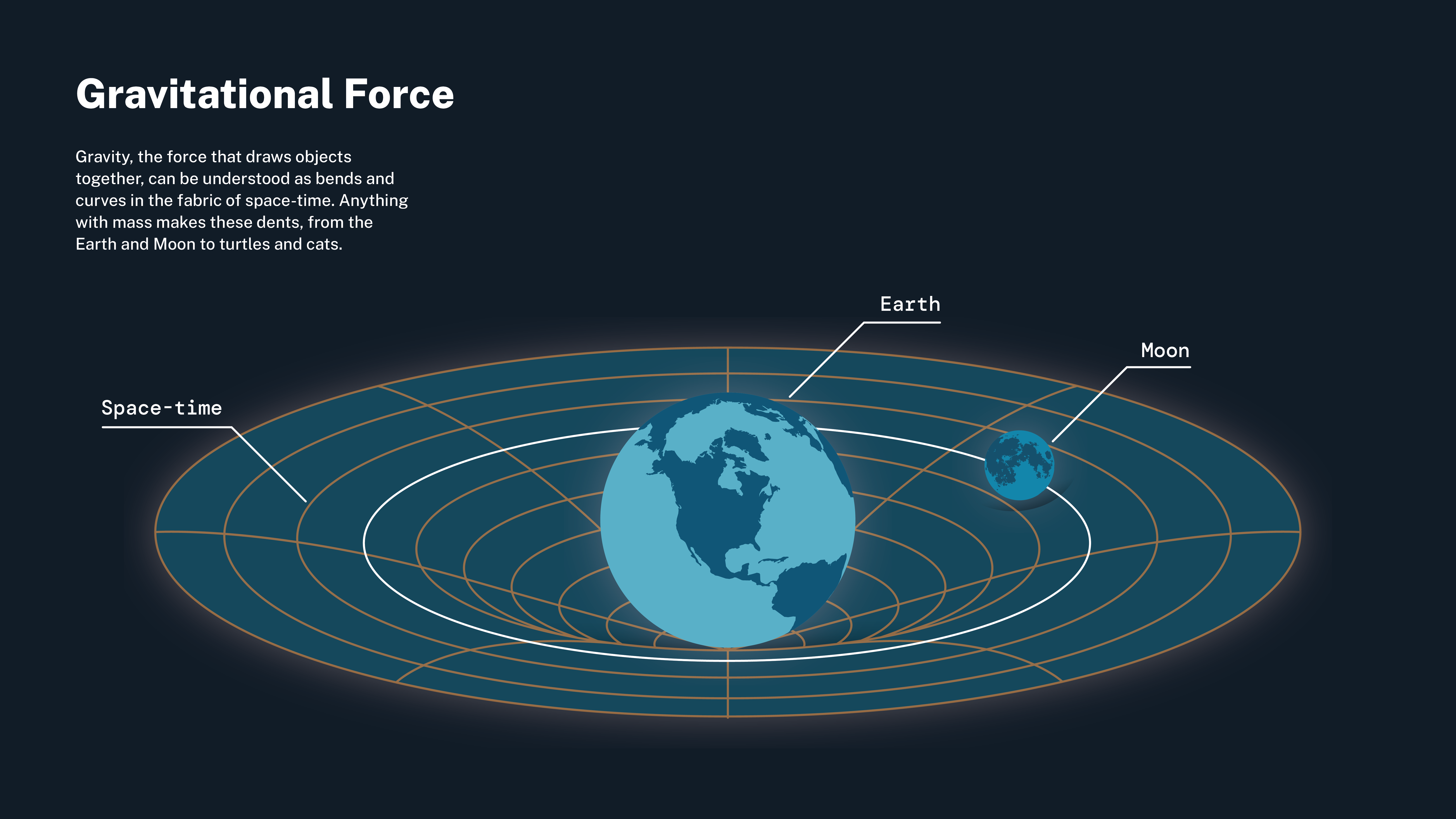

Now, if you want to get really fancy, we have to admit that Newton's earth gravitational force formula isn't the "ultimate" truth. Albert Einstein came along in 1915 and basically said gravity isn't a force at all. Instead, he argued that mass warps the "fabric" of space-time.

Think of a trampoline with a bowling ball in the middle. The ball creates a dip. If you roll a marble nearby, it follows the curve of that dip. That’s how Einstein viewed Earth’s gravity. For almost everything we do on Earth, Newton’s math is more than enough. But for things like the orbit of Mercury or the way light bends around stars, we have to use Einstein’s General Relativity.

Putting the formula to work

If you want to actually use this knowledge, start by looking at your surroundings. Gravity isn't just a number; it's a relationship.

If you want to calculate the force of gravity on any object, you just need its mass in kilograms. Multiply that by $9.8$. That’s the force in Newtons. To convert Newtons to pounds (if you're in the US), divide by $4.45$.

👉 See also: iRobot Mop and Vacuum: Why the Roomba Combo is Actually Changing My Mind About 2-in-1s

It's also worth thinking about "escape velocity." To actually leave Earth's gravity behind and head to Mars, you have to overcome the pull defined by the earth gravitational force formula. That requires a speed of about $11.2$ km/s. Every rocket launch is a direct, violent argument with the math we just discussed.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

- Check your local gravity: Use a "gravity map" online to see if you live in a high or low gravity zone. Most people are surprised to find it varies by city.

- Calculate your weight on other planets: Use the formula but swap Earth's mass and radius for Mars or Jupiter. You'll find you’d weigh only 38% of your current weight on Mars.

- Observe the tides: Next time you’re at the beach, remember that you’re watching the earth gravitational force formula (and the moon's version of it) play out in real-time across millions of gallons of water.

- Weight vs. Mass: Remind yourself that your mass (the amount of "stuff" in you) never changes, but your weight is just a measurement of how hard Earth is pulling on that stuff. Go to the top of a mountain, and you technically weigh less.

Gravity is the most familiar yet most mysterious thing in our lives. We can calculate it to ten decimal places, yet we still aren't 100% sure what "carries" the force—some scientists think it’s a particle called a graviton, but we haven’t found it yet. Until then, we have the math. It works, it’s reliable, and it’s the only reason we aren't all floating away into the sky right now.