You’re sitting at a concert. The bass hits your chest so hard your ribs feel like they’re vibrating. That’s not magic. It’s a mechanical wave. Specifically, it’s a longitudinal wave of pressure ripping through the air molecules. Most people think of waves as just "things that move," but in physics, a mechanical wave is a very specific, stubborn beast. It requires a medium. It needs stuff to travel through—air, water, steel, or even the ground beneath your boots. Without a medium, a mechanical wave is nothing. It simply doesn't exist.

Take a second to think about space. You've seen the movies where a ship explodes and there’s a massive "BOOM." In reality? Total silence. Because there is no air in the vacuum of space to carry the vibration, sound—one of our most common examples of mechanical waves—cannot travel. It's a lonely concept when you really dwell on it.

The Physicality of Motion

What makes a wave "mechanical" anyway? Basically, it’s the transfer of energy through a material without the material itself actually going anywhere permanent. Think of a stadium wave. You stand up, you sit down. Your neighbor does the same. The "wave" travels all the way around the arena, but you’re still in seat 42B. You didn't move to the other side of the stadium; only the energy of the "stand up" motion did.

This is the essence of deformation and restoration. When you pluck a guitar string, you deform it. The string’s elasticity—its desire to go back to being straight—creates the wave. If the material isn't elastic or doesn't have inertia, you aren't getting a wave. You're just breaking something.

The Heavy Hitters: Sound and Water

Sound is the quintessential example. When you speak, your vocal cords push air molecules together (compression) and then they spread apart (rarefaction). This creates a longitudinal wave where the particles move parallel to the direction the wave is traveling. It’s like a Slinky being pushed and pulled from one end. Interestingly, sound travels way faster in solids than in air. In dry air at 20°C, sound moves at about 343 meters per second. In steel? It screams through at over 5,000 meters per second. This is why in old Westerns, characters put their ear to the train tracks. They’re literally "listening" to a faster version of the mechanical wave.

Then you have water waves. These are a bit of a hybrid. On the surface, they look like transverse waves (up and down), but the molecules actually move in little circles. This is called a surface wave. If you’ve ever been surfing, you know that the water isn't actually moving toward the shore as much as the energy is. The water just bobbles you around until the wave "breaks" because the bottom of the wave hits the seafloor and slows down while the top keeps hauling.

Seismic Waves: When the Earth Becomes a Medium

Earthquakes provide some of the most terrifyingly powerful examples of mechanical waves. When a fault line slips, it releases a massive amount of stored elastic potential energy. This energy radiates outward in two main types of "body waves": P-waves and S-waves.

P-waves (Primary waves) are longitudinal. They are the fastest and usually the first things a seismograph picks up. They can travel through both solid rock and liquid (like the Earth's outer core). S-waves (Secondary waves) are transverse. They move the ground up and down or side to side. Crucially, S-waves cannot travel through liquids. This is actually how scientists figured out the Earth has a liquid outer core—they noticed "shadow zones" where S-waves just disappeared during big quakes.

- P-waves: The push-pull motion.

- S-waves: The shear motion (slower, more destructive).

- Surface waves: Rayleigh and Love waves that roll along the crust like ocean swells.

These aren't just abstract concepts. Engineers have to build skyscrapers in Tokyo or San Francisco with "tuned mass dampers"—giant weights that counteract these mechanical waves so the building doesn't shake itself into a pile of toothpicks.

💡 You might also like: Why an Image of an Iris Tells a Much Bigger Story Than You Think

The "Slinky" Science and Everyday Tech

You probably have examples of mechanical waves in your pocket right now. Your phone's haptic motor? That’s a mechanical vibration. The ultrasound machines used in hospitals? Those are high-frequency sound waves (mechanical) that bounce off internal organs to create an image. The machine measures the "echo" or the reflection of those waves. It's the same principle bats use for echolocation.

- Ultrasound imaging: High-frequency mechanical pulses.

- Sonar: Used by submarines to map the dark ocean floor.

- Acoustic guitars: The hollow body amplifies the mechanical vibration of the strings.

- Shock waves: Like a sonic boom when a jet breaks the sound barrier.

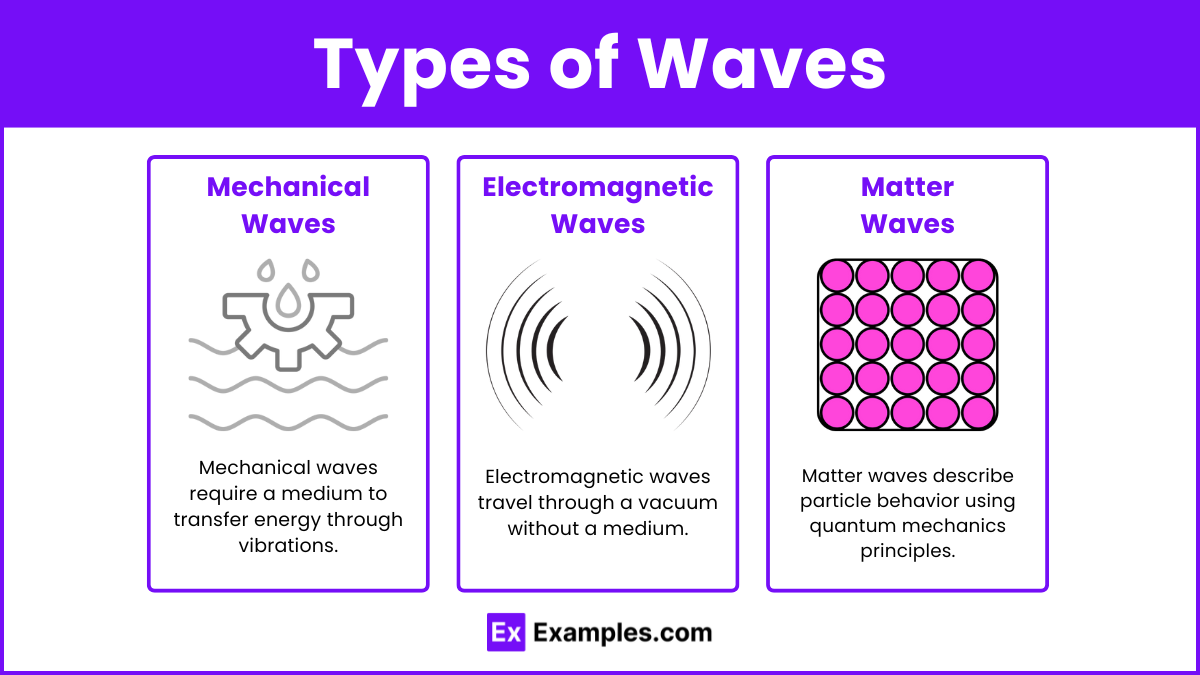

One thing people often get wrong is confusing mechanical waves with electromagnetic (EM) waves. Light, radio, and X-rays are EM waves. They don't need a medium. They can zip through the void of space at $c$ (the speed of light). Mechanical waves are the "blue-collar" waves. They have to do the hard work of pushing atoms around.

Why Tension and Density Matter

The speed of a mechanical wave isn't fixed. It changes based on the medium's properties. For a wave on a string, the velocity ($v$) is determined by the tension ($T$) and the linear mass density ($\mu$).

$$v = \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}}$$

If you tighten a guitar string, the wave moves faster, and the pitch goes up. If you use a thicker, heavier string (higher $\mu$), the wave moves slower, and the pitch drops. This is why the low E-string on a guitar is thick and heavy while the high E-string is thin and tight. It’s all just playing with the physics of mechanical waves to make art.

In gases, it’s about temperature. Hotter air means molecules are moving faster and hitting each other more often, which allows the mechanical wave to pass through more efficiently. This is why your favorite outdoor concert might sound slightly different on a humid, 90-degree night versus a crisp autumn evening.

The Shocking Reality of Shock Waves

Ever seen a "vapor cone" around a fighter jet? That's a mechanical wave pushed to the limit. When an object moves faster than the speed of sound in that medium, the pressure waves it creates can't get out of the way fast enough. They pile up. This creates a shock wave—a sudden, nearly discontinuous change in pressure, temperature, and density.

The "crack" of a whip is actually a mini sonic boom. The tip of the whip is moving so fast it breaks the sound barrier, creating a localized shock wave. It’s a violent, high-energy version of the same mechanical principles that let you hear a whisper across a room.

Nuance: The Damping Problem

In a perfect world (the kind physics professors love), a mechanical wave would travel forever. But we live in a world with friction and internal resistance. This is called damping. Energy is lost as heat. If you hit a bell, it eventually stops ringing because the mechanical energy is dissipated into the surrounding air and through the metal itself.

Even the ocean eventually swallows its own waves. Without constant input from the wind, the surface of the water would eventually become glass-still. This loss of amplitude over time is a fundamental constraint for engineers designing anything from noise-canceling headphones to earthquake-proof bridges.

Practical Insights for Real-World Application

Understanding these waves isn't just for passing a test. It has massive implications for how we live.

If you're looking to soundproof a room, don't just think about "blocking" sound. Think about "decoupling." Since sound is a mechanical wave, it needs a physical path. If you build a room within a room where the walls don't touch, the wave has no medium to travel through. It dies.

For those interested in home maintenance, knowing how waves travel through your floorboards can help you find a leak or a structural squeak. In the medical field, shockwave therapy (lithotripsy) uses mechanical waves to pulverize kidney stones without a single incision. It's literally using physics to smash rocks inside the human body.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding

To truly grasp how these waves behave, stop reading and start observing. Go to a local pool and watch how waves reflect off the concrete edges—that’s wave reflection and interference in real-time. Or, next time you're at a stadium, watch the "crowd wave" and realize you're looking at a macro-model of particle displacement.

Study the difference between "phase velocity" and "group velocity" if you want to get into the weeds of how complex wave packets move. Most importantly, remember that every sound you hear and every tremor you feel is a physical conversation between particles, a mechanical chain reaction that connects you directly to the source of the energy.