You’re probably reading this because of a tiny strand of glass. It’s thinner than a human hair. Honestly, it’s kind of wild when you think about it. Right now, pulses of light are screaming through these glass threads at speeds that make old-school dial-up look like a horse and buggy in a drag race. We talk about "the cloud" or "high-speed internet" like it’s magic, but it’s actually just a massive, global plumbing system for light.

Understanding how fiber optic cable works isn't just for network engineers or guys in hard hats. It’s the backbone of everything. From your Netflix binge to high-frequency stock trading, it all sits on this tech. Copper wires—the stuff that powered our phones for a century—just can't keep up anymore. They're too slow, too noisy, and they leak energy like a sieve. Fiber is different. It’s elegant.

Total Internal Reflection: The Physics of Not Leaking Light

The whole system relies on a trick of physics called Total Internal Reflection (TIR). Imagine you’re standing underwater in a swimming pool with a flashlight. If you point it straight up, the beam hits the air. But if you tilt that flashlight at a sharp enough angle, the light doesn't escape into the air. It bounces off the surface and stays in the water.

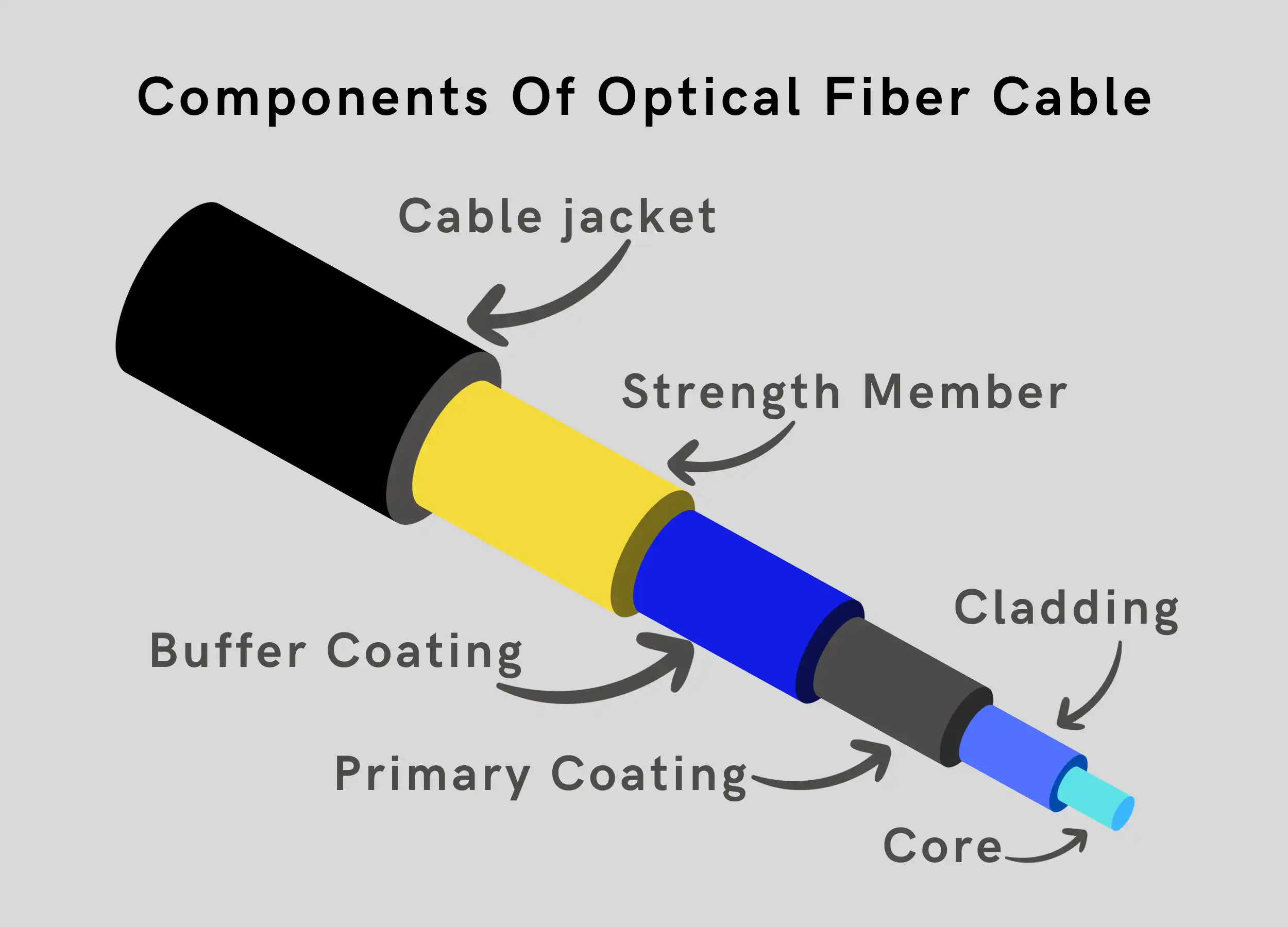

That’s basically what’s happening inside a fiber optic cable. The cable has two main layers: the core and the cladding. The core is made of incredibly pure glass. Surrounding it is the cladding, which is also glass but has a different "refractive index." Because the cladding is less dense (optically speaking) than the core, it acts like a perfect mirror. When a laser pulses into the core, the light hits the boundary between the two materials and bounces back inward. Over and over. Thousands of times per kilometer.

It’s efficient. Unlike electricity in a copper wire, which generates heat and loses strength because of resistance, light just keeps cruising. Sure, there’s some "attenuation"—that’s the fancy word for signal loss—due to impurities in the glass or scattering, but it’s nothing compared to the 100-meter limit of a standard Ethernet cable.

The Bits and Bytes of Light

How do you turn a YouTube video into a beam of light? Binary. It always comes back to zeros and ones. A transmitter at one end (usually a laser or an LED) switches on and off incredibly fast. Light on? That’s a 1. Light off? That’s a 0.

These aren't just your average light bulbs. We're talking about Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Lasers (VCSELs) or edge-emitting lasers that can pulse billions of times per second. It’s dizzying. At the other end, a photodiode—basically a high-tech light sensor—catches those pulses and converts them back into electrical signals that your router or computer can understand.

Single-Mode vs. Multi-Mode: Choosing Your Lane

Not all fiber is created equal. You’ve probably heard people argue about which is better, but it really depends on what you're trying to do.

- Single-Mode Fiber (SMF): This has a tiny core, usually around 9 microns wide. Because the path is so narrow, the light travels in a single, straight-ish line. This is the heavy hitter. It’s used for long distances—think miles and miles under the ocean or between cities. Because there’s only one "mode" of light, there's almost no signal overlap or "modal dispersion."

- Multi-Mode Fiber (MMF): The core here is much wider, typically 50 or 62.5 microns. This allows multiple light rays to bounce around inside at different angles. It’s cheaper and easier to work with, but the signals start to get muddy over long distances because different rays take slightly different paths. You’ll mostly see this inside data centers or office buildings.

It’s a bit like the difference between a high-speed rail line and a five-lane highway. One is for going really far, really fast; the other is for moving a lot of stuff over a shorter distance.

Why Copper is Officially a Dinosaur

Copper is heavy. It’s expensive. It’s also a magnet for electromagnetic interference (EMI). If you run a copper power line next to a copper data line, the electricity from the power line "bleeds" into the data line, causing noise and errors.

Fiber doesn't care about your power lines. It’s glass. Glass is an insulator. You could wrap a fiber optic cable around a high-voltage transformer and the signal wouldn't flicker. This is why how fiber optic cable works is so vital for industrial environments or places with lots of radio interference.

There’s also the bandwidth issue. Copper is limited by the frequency it can carry before the signal just gives up. Fiber? We haven't even found the ceiling yet. Using a technique called Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM), engineers can send multiple "colors" of light through the same fiber at the same time. It’s like taking a single pipe and realizing you can fit twenty different colored streams of water through it without them ever mixing.

The Real-World Grind: Splicing and Breaking

Glass is fragile, right? Sort of. While a bare fiber strand is easy to snap, the cables you see being buried in the street are ruggedized with Aramid yarn (the stuff in Kevlar vests) and thick plastic jackets.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Google Pixel Watch App is Actually the Best Part of the Experience

The hardest part of working with fiber is "splicing." If a backhoe digs up a line, you can't just twist the ends together and wrap it in electrical tape. You need a fusion splicer. This machine uses an electric arc to melt the two ends of glass together with micron-level precision. If they're off by even a tiny fraction, the light will scatter, and your signal dies. It’s a specialized skill that combines physics with the steady hand of a surgeon.

The Latency Secret

People obsess over "speed" (bandwidth), but for gamers or stock traders, latency is the real king. Latency is the delay between sending a command and getting a response. Because light in glass travels at about 70% of the speed of light in a vacuum, it is incredibly fast.

However, it’s not instantaneous. If you're playing a game on a server in London while you're in New York, that light has to travel through thousands of miles of glass, passing through "repeaters" (amplifiers) every 50 to 80 kilometers to keep the signal strong. Every piece of equipment adds a few microseconds of delay. Even so, fiber is the lowest-latency medium we have for long-distance communication.

Practical Steps for the Real World

If you're looking to upgrade your home or business, don't just look at the "up to 1 Gbps" marketing fluff.

1. Check the "Last Mile": Many providers claim they offer fiber, but they actually run fiber to a node in your neighborhood and then use old copper coax cable for the "last mile" to your house. This is called HFC (Hybrid Fiber-Coaxial). It’s fine, but it’s not "True Fiber" (FTTH - Fiber to the Home). Demand FTTH if you want symmetrical upload and download speeds.

2. Invest in the Right Hardware: If you have a 2 Gbps fiber connection but you're using an old Wi-Fi 5 router, you're flushing money down the drain. You need a router with a 2.5 GbE WAN port and devices that support Wi-Fi 6E or 7 to actually feel that speed.

3. Protect the Bend: If you have fiber inside your house, never bend the cable at a sharp 90-degree angle. You’ll create "macro-bends" that leak light and kill your speeds. Keep your loops wide.

4. Clean the Ends: If you're a pro setting up your own SFP modules, use a fiber cleaning pen. A single speck of dust on the end of a fiber connector is like a boulder blocking a tunnel. It ruins everything.

The shift to fiber isn't just a luxury. It's the foundation of a world where we're moving more data than ever before. Understanding the "how" helps you make better decisions about the tech you buy and the services you pay for. Copper had a good run, but the future is made of glass.