Mercury is a weirdo. It’s the smallest planet, the closest to the Sun, and honestly, one of the most difficult things in our solar system to actually get a clear look at. If you’ve ever scrolled through social media and seen a vibrant, rainbow-colored sphere labeled as the "first real photo of Mercury," you’ve probably been lied to. Or, at the very least, you’ve been shown a "false-color" map.

The truth is much more subtle.

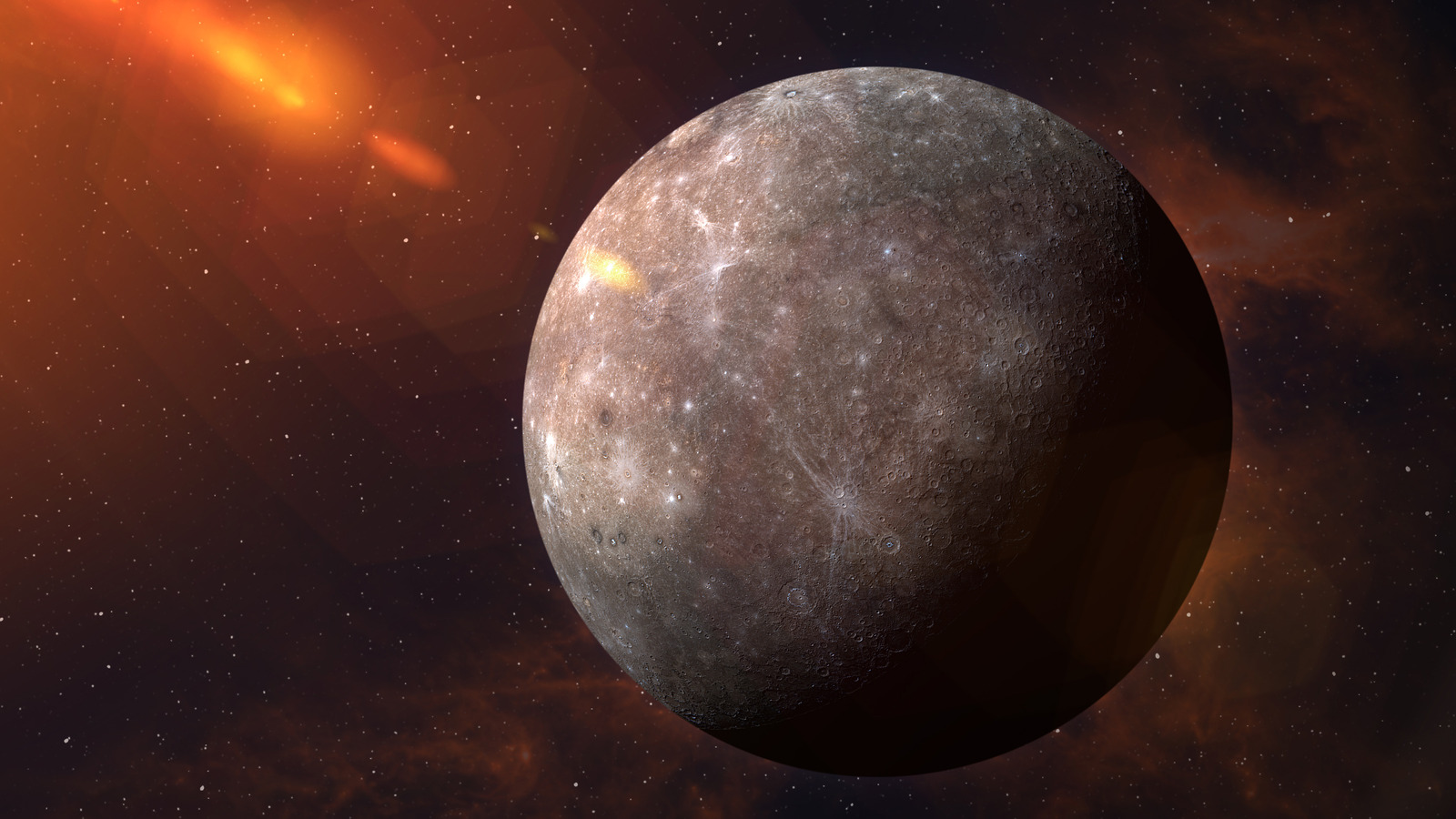

To the naked eye—or if you were standing on a very heat-shielded spacecraft nearby—Mercury looks like a battered, dusty, greyish-brown golf ball. It looks a lot like our Moon. People often get disappointed by that, but the story behind how we actually captured a real photo of Mercury is a masterclass in engineering survival.

Why We Have So Few Photos

For decades, we basically had nothing. While we had high-resolution maps of Mars and stunning voyagers’ shots of Jupiter’s moons, Mercury remained a blurry blob.

The Sun is the problem.

Try taking a photo of a moth fluttering an inch away from a stadium floodlight. That’s what it’s like for NASA or the ESA to point a camera at Mercury. The gravitational pull of the Sun is so immense that any spacecraft headed that way picks up terrifying amounts of speed. Slowing down enough to enter orbit requires more fuel than most rockets can carry.

📖 Related: Netgear Nighthawk C7000: Why This Modem Router Combo Still Makes Sense for Most Homes

Then there’s the heat.

The side of Mercury facing the Sun hits roughly 430°C. That’s enough to melt lead. Most cameras would simply fry. Because of this, we’ve only had two major missions that successfully gave us a real photo of Mercury in high definition: Mariner 10 in the 1970s and MESSENGER in the 2000s.

Mariner 10 was a pioneer, but it only managed to photograph about 45% of the surface. We were literally in the dark about half the planet until 2008. When the MESSENGER (Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging) spacecraft finally settled into orbit, it changed everything. It took over 250,000 images, giving us the first complete look at this scorched world.

Real Color vs. False Color: Don't Be Fooled

If you search for a real photo of Mercury, you’ll likely see a version that looks like it’s covered in blue, red, and yellow splotches.

That isn't what it looks like.

Scientists use "false color" to highlight chemical differences on the surface. The blue areas are often "low-reflectance material," which basically means rocks that are rich in minerals like carbon. The tan or reddish areas are usually plains formed by ancient lava flows. It’s useful for geologists, but it’s not "real" in the sense of human vision.

A true-color image is drab. It’s monochrome. It’s a world of greys.

The Caloris Basin

One of the most striking features you’ll see in a genuine image is the Caloris Basin. It’s one of the largest impact craters in the entire solar system, stretching about 950 miles across. It’s so big that the impact that created it actually sent shockwaves through the entire planet, creating a "weird terrain" of hills and ridges on the exact opposite side of the globe.

📖 Related: Why Every Picture of International Space Station Actually Matters

Why Mercury Looks Like the Moon

At first glance, you might confuse a real photo of Mercury with the Moon. They both have that heavily cratered, "dead" look. But there are key differences if you know where to look. Mercury has "lobate scarps"—huge, winding cliffs that look like wrinkles.

Basically, the planet shrank.

As Mercury’s massive iron core cooled over billions of years, the planet literally contracted, causing the crust to wrinkle like a raisin. You don't see those types of massive tectonic wrinkles on the Moon.

The BepiColombo Era

Right now, we are in the middle of a new chapter. The BepiColombo mission, a joint venture between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), is currently on its way to Mercury.

It’s already sent back "flyby" photos.

These images are fascinating because they are captured by "monitoring cameras" attached to the side of the spacecraft. They show the planet's surface in stark, grainy detail, often with parts of the spacecraft’s antenna or boom in the frame. It feels raw. It feels like a real GoPro shot from deep space.

💡 You might also like: How to actually search Facebook for posts without losing your mind

BepiColombo is actually two different orbiters stacked together. They won't separate until they reach their final destination in late 2025 or early 2026. Until then, every real photo of Mercury we get from this mission is a "sneak peek" taken during gravity-assist maneuvers.

The Mystery of the Ice

It sounds like a joke. How can a planet that close to the Sun have ice?

But photos—specifically radar imaging and shadow analysis from MESSENGER—confirmed it. There are deep craters at the North and South poles that are in "permanent shadow." The Sun never reaches the bottom of them. In those spots, it stays around -170°C.

NASA’s images suggest there are actually deposits of water ice and organic material hidden in those shadows. This is why a real photo of Mercury is so much more than just a picture of a rock; it’s a map of contradictions.

How to Find Authentic Images

If you want to see the real deal without the "artistic interpretation," you have to go to the source.

- NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS): This is the raw warehouse.

- The MESSENGER Mission Gallery: Look for images labeled "monochrome" or "true color."

- ESA’s BepiColombo Twitter/X or Flickr: They post the most recent flyby images there.

Misconceptions You Should Ignore

You’ll often see "photos" of Mercury where the planet looks like a molten ball of fire. That’s fake. It’s a computer-generated image (CGI) based on the fact that Mercury is hot.

Another common error is people showing photos of the transit of Mercury. This is when the planet passes in front of the Sun. In these photos, Mercury is just a tiny, perfectly black circle against a giant orange background. While these are "real" photos, they don't tell you anything about the planet's surface.

The real surface is a graveyard of craters. There’s the Rembrandt crater, which is over 400 miles wide. There are "hollows"—strange, bright depressions that look like someone took a scoop out of the surface. We still don't fully understand what causes them, though some think it’s chemicals evaporating into space.

What to Look for Next

The next 12 to 18 months will be the "Golden Age" for Mercury photography. As BepiColombo prepares to enter its final orbit, the quality of the photos will jump from "grainy flyby" to "high-definition mapping."

If you are looking for a real photo of Mercury to use for a project or just for your own curiosity, always check the metadata or the caption for the phrase "false color." If it looks like a disco ball, it’s a data map. If it looks like a lonely, grey rock in the middle of a black void, you’ve found the real Mercury.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts:

- Check the "Raw" Feeds: Follow the ESA’s BepiColombo mission logs directly. They release unedited images before they are processed for the public.

- Learn the Landmarks: Familiarize yourself with the "Caloris Basin" and "Discovery Scarp." These are the two biggest giveaways that you are looking at Mercury and not the Moon.

- Verify the Source: Use the NASA Photojournal and filter by "Image Content: Surface" to avoid getting buried in transit photos or artistic renderings.

- Use Modern Tools: Apps like "Eyes on the Solar System" by NASA let you see exactly where the MESSENGER or BepiColombo spacecraft were when they took specific shots, providing the context that a static JPEG often loses.