Look at a standard Mercator projection map. Iceland looks huge. It’s sitting up there, floating in the North Atlantic like a massive, icy sentinel guarding the gateway to the Arctic. But honestly? Maps lie. If you’re trying to find Iceland on a map, you’re likely staring at a distorted piece of cartography that makes this island nation look like the size of Western Europe. In reality, it’s about the size of Kentucky or South Korea. It’s a tiny speck of volcanic rock that just happens to have a very loud geological personality.

Most people look for it and think it’s part of Scandinavia. It isn’t. Not geographically, anyway. While it shares deep cultural and linguistic roots with Norway and Denmark, Iceland is a lonely outpost. It’s located at the confluence of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. To get specific, you’re looking at the coordinates 64° 08' N and 21° 56' W for the capital, Reykjavík. It’s way out there.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge: A Country Tearing Itself Apart

When you locate Iceland on a map, you aren’t just looking at a country; you’re looking at a geological car crash in slow motion. It sits directly on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This is the underwater mountain range where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates are pulling away from each other.

Most of this ridge is buried under miles of ocean water. Iceland is the only place where it rises above sea level.

📖 Related: Reading the River: What a 250 cfs water flow river Actually Looks Like

Think about that for a second.

You can literally stand in a crack in the earth at Þingvellir National Park and realize your left foot is on Europe and your right foot is on North America. They’re moving apart at about two centimeters a year. It’s a slow-motion breakup that defines everything about the island’s existence. This rift is why the country is a literal pressure cooker of geothermal energy. Because the crust is so thin here, magma is closer to the surface than almost anywhere else on Earth.

Why the "Greenland is Ice, Iceland is Green" Thing is a Half-Truth

We’ve all heard the old joke. The Vikings swapped the names to trick people. Erik the Red wanted people to go to the icy wasteland of Greenland, so he called it something pretty. Meanwhile, they called the lush island "Iceland" to keep it for themselves.

It’s a great story. It’s also mostly nonsense.

Flóki Vilgerðarson, one of the first Norsemen to intentionally sail there, gave the island its name after a particularly brutal winter. He climbed a mountain, saw a fjord full of drift ice, and—being a literal-minded Viking—called it Ísland. Simple as that.

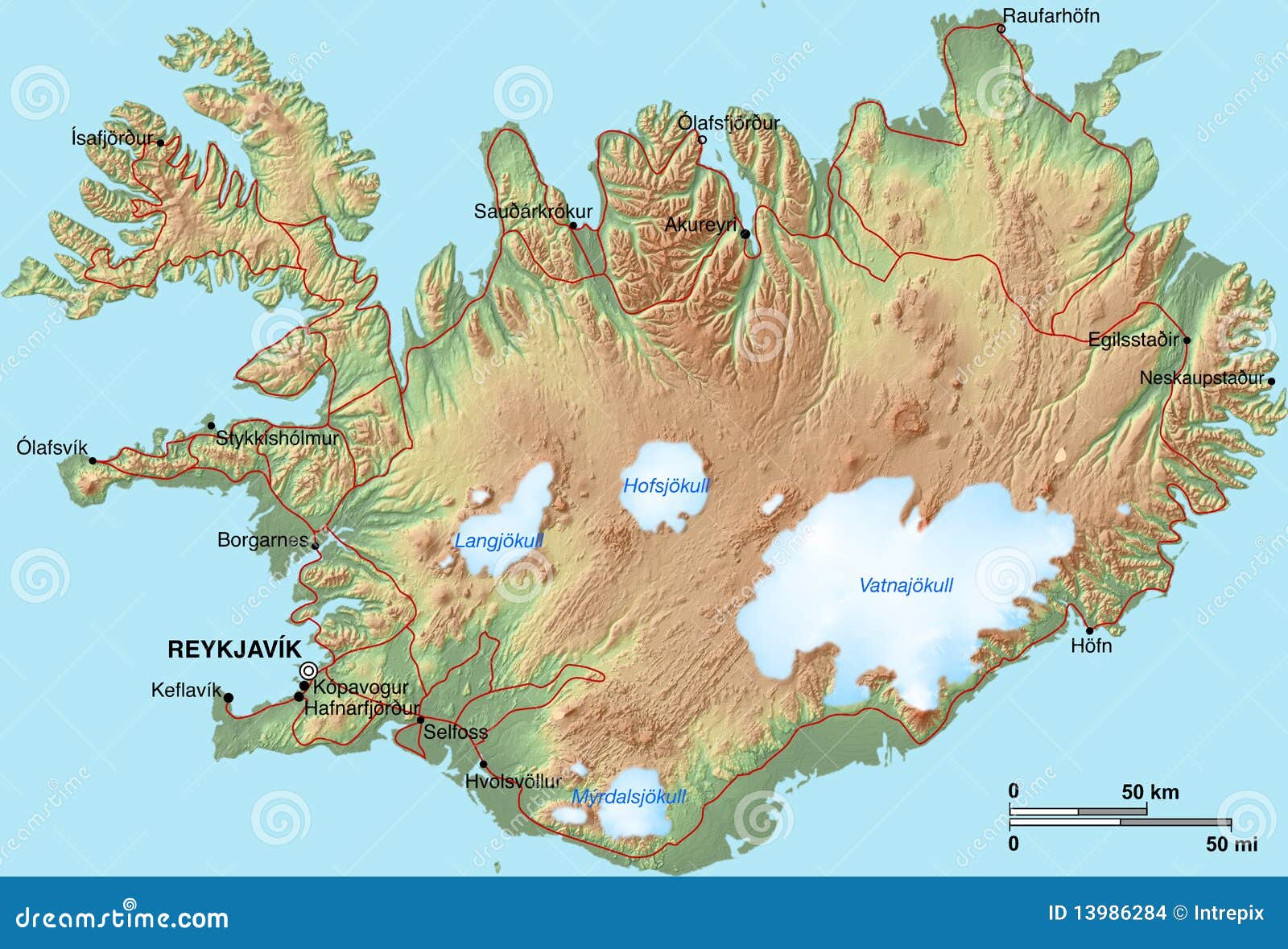

If you look at Iceland on a map today, you’ll see that about 11% of it is covered by permanent glaciers. Vatnajökull isn't just a patch of ice; it's the largest ice cap in Europe by volume. So, yeah, the "ice" part of the name is actually pretty accurate, especially when you’re staring at a wall of blue pressurized ice that’s been there for centuries.

Where Exactly Is It? Neighbors and Proximity

Iceland is isolated.

Its nearest neighbor is Greenland, about 290 kilometers (180 miles) away. Scotland is roughly 800 kilometers (500 miles) to the southeast, and Norway is nearly 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) to the east. It is the westernmost country in Europe.

Interestingly, despite its proximity to the Arctic Circle, it’s not as cold as you’d think. You can thank the North Atlantic Current for that. This warm ocean current snakes its way up from the Gulf of Mexico, bringing relatively temperate air to the southern and western coasts. Without it, Iceland would be an uninhabitable ice block. Instead, winter temperatures in Reykjavík often hover around freezing—which is actually warmer than New York or Chicago in January.

The geography is weirdly deceptive.

You might see the Arctic Circle cutting through the very top of the country on a map. Actually, the mainland stays just south of it. Only the tiny island of Grímsey, which sits about 40 kilometers off the north coast, is officially bisected by the Arctic Circle.

Mapping the Regions: A Quick Breakdown

- The South Coast: This is where the postcards come from. Waterfalls like Seljalandsfoss and the black sand beaches of Vík.

- The Westfjords: The gnarled, hand-shaped peninsula in the northwest. It’s the oldest part of Iceland, geologically speaking, and it's crumbling into the sea. Very few people go here because the roads are terrifying.

- The Highlands: The vast, uninhabited interior. If you look at a satellite map of Iceland, this is the brown and grey middle part. It’s a desert of volcanic ash and lava fields. No one lives here. You can’t even drive here in the winter.

- The Eastfjords: Remote, foggy, and filled with tiny fishing villages that look like they haven't changed since the 1950s.

The Distortion of the Mercator Projection

We need to talk about why Iceland on a map looks so huge. Most digital and paper maps use the Mercator projection. This system was designed for sailors in the 1500s because it preserves straight lines for navigation.

👉 See also: Why Hotel Indigo Edinburgh Princes Street is Still the Smartest Move for a Weekend Away

The cost? It stretches everything near the poles.

On a Mercator map, Greenland looks larger than Africa. In reality, Africa is 14 times larger than Greenland. Iceland suffers from the same "inflation." It looks like it could swallow the UK, but the UK is actually more than double its size in land area.

When you’re planning a trip or studying the geography, use a globe or a Gall-Peters projection to get a better sense of the scale. It’s a small island. You can drive the entire Ring Road—the highway that circles the country—in about 15 to 17 hours of pure driving time. Of course, you shouldn’t do that. You’d miss the volcanos.

Human Impact and the "Empty" Map

One of the most striking things about looking at a population map of Iceland is the emptiness.

Almost 80% of the country is uninhabited.

The population is around 375,000 people. To put that in perspective, that’s fewer people than live in the city of Wichita, Kansas. And about 60% of those people live in the Greater Reykjavík area.

When you leave the capital, the map becomes a series of long, empty stretches punctuated by the occasional farm or cluster of houses. This isolation has shaped the Icelandic character. They are incredibly self-reliant, tech-savvy, and remarkably calm when the ground starts shaking.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Iceland

If you are moving beyond the digital map and actually planning to visit this coordinate in the North Atlantic, here is what you need to do:

1. Don't trust Google Maps travel times. The map might say a drive takes three hours. In Iceland, "three hours" doesn't account for 50 mph lateral winds, sheep standing in the middle of the road, or you stopping every ten minutes to take a photo of a rainbow. Double your estimated travel times.

✨ Don't miss: Monthly Weather in Denver: What Most People Get Wrong

2. Download offline maps. Cell service is surprisingly good even in the middle of nowhere, but the Highlands are a dead zone. If you’re heading into the interior, Paper maps (yes, the physical ones) and GPS units are mandatory.

3. Use the right map layers. For hiking, standard maps are useless. Use the Icelandic search and rescue site, Safetravel.is, and the Icelandic Meteorological Office (vedur.is) for real-time maps on wind, ash, and seismic activity. In Iceland, the map changes. A new lava flow can literally erase a road in a matter of hours.

4. Respect the "F-Roads." When you see an "F" before a road number on an Icelandic map, it means "Fjallvegar" (Mountain Road). These are not suggestions. They require 4x4 vehicles and often involve crossing unbridged rivers. Do not take a small rental car onto an F-road unless you want to pay for a very expensive rescue and a drowned engine.

5. Check the "Road.is" map daily. The Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration provides a live map showing road conditions. Green means good, yellow means icy, and red means the road is closed. This map is more important than your GPS. If the map says the road is closed, it isn't a challenge; it's a warning that the wind might blow your car off a cliff.

Finding Iceland on a map is the easy part. Understanding the scale, the volatile geology, and the sheer emptiness of the landscape is what actually matters. It’s a country that refuses to stay still, literally growing larger every year as the tectonic plates pull apart, creating new land out of fire and ice.