You're standing in a lab or maybe just your kitchen. You have a weirdly shaped object. You know what it's made of—maybe it's a slab of granite or a pour of heavy cream—and you know exactly how much space it takes up. But you don't have a scale. Or maybe the object is a planet. You definitely aren't weighing a planet on a bathroom scale. This is where the math kicks in. Honestly, finding mass given density and volume is one of those fundamental skills that feels like a magic trick once you stop overthinking the algebra.

It’s about relationships.

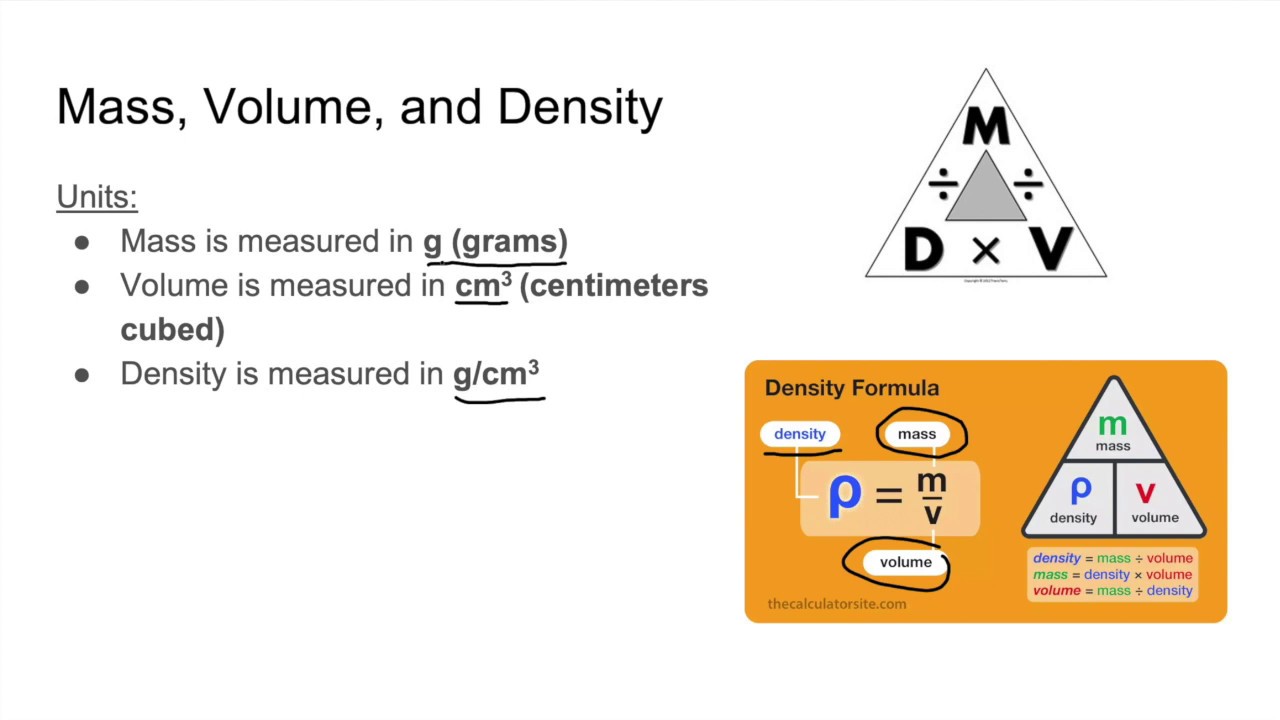

Most people get tripped up because they try to memorize a triangle diagram they saw in a textbook once. Forget the triangle for a second. Think about a sponge versus a brick. They might be the exact same size (volume), but the brick has way more "stuff" packed into that space (density). If you want to know how heavy that brick is without picking it up, you just need to know how tightly that matter is packed.

The Core Logic of the Equation

At its heart, density is just a ratio. It tells us how much mass is jammed into a specific unit of volume. If you have the density and you have the total volume, you’re basically just scaling that ratio up.

The formal equation looks like this:

$$m = \rho \times V$$

In this setup, $m$ represents mass, $V$ is volume, and that weird curly "p" is actually the Greek letter rho ($\rho$), which scientists use for density. You just multiply them. It’s that simple. If you have a substance with a density of 5 grams per cubic centimeter and you have 10 cubic centimeters of it, you have 50 grams of mass.

Watch Out for the Unit Trap

This is where the real-world errors happen. I’ve seen students and even experienced builders mess this up because they didn't check their units. You cannot multiply a density measured in kilograms per cubic meter by a volume measured in liters and expect a sane answer. Well, you'll get an answer, but it’ll be wrong.

Everything has to match.

📖 Related: iPhone 13 Forest Green: Why This Specific Shade Still Has a Massive Cult Following

If your density is in $g/cm^3$, your volume must be in $cm^3$. If your volume is in gallons but your density chart is in $lb/ft^3$, you have some converting to do first. Always look at the denominator of your density unit. That tells you exactly what your volume unit needs to be before you touch a calculator.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

It isn't just for passing a chemistry quiz.

Engineers use this daily. Imagine you’re designing a bridge. You know the volume of the steel beams required. You know the density of the specific grade of steel. By finding mass given density and volume, you calculate the total weight the concrete pillars need to support. If you’re off by a decimal point, the bridge fails. It’s high-stakes math.

Even in hobbyist circles, like 3D printing, this is huge. Most slicing software will tell you the volume of plastic needed for a print. If you know the density of your filament (like PLA or PETG), you can figure out exactly how many grams the final piece will weigh. This helps you price your work or see if you have enough left on the spool. No one wants a print to fail at 90% because they ran out of plastic.

Real-World Case: The Gold Bar Test

Let’s talk about Archimedes. Legend says he had to figure out if a crown was solid gold without melting it down. He used displacement to find the volume. Since the density of pure gold is a known constant—roughly 19.3 grams per cubic centimeter—he could calculate what the mass should be.

If you have a "gold" bar that occupies 100 cubic centimeters, its mass must be 1,930 grams. If it weighs 1,500 grams instead? You’ve been cheated. Someone mixed in a cheaper, less dense metal like silver or copper.

Dealing with Gases and Temperature

Density isn't a fixed number for everything. This is a nuance many articles skip. While solids like lead or wood have pretty stable densities, liquids and especially gases are picky.

Water is a classic example. At $4^{\circ}C$, its density is almost exactly $1 \text{ g/cm}^3$. But as it heats up, it expands. The volume increases while the mass stays the same, which means the density drops. If you are calculating the mass of a massive tank of oil in the heat of a Texas summer versus a New York winter, your "fixed" density might lead you astray. For gases, the pressure matters even more.

Always check if your density value is "standard." Most tables assume room temperature and standard atmospheric pressure.

The Steps to Getting it Right

- Identify your knowns. Write down the volume and the density.

- Check the units. This is the non-negotiable step. Convert if necessary.

- Perform the multiplication. Mass = Density $\times$ Volume.

- Sanity check. Does the number make sense? If you’re calculating the mass of a cup of water and you get 50 kilograms, you probably moved a decimal point the wrong way.

Common Misconceptions: Mass vs. Weight

I should probably mention that mass and weight aren't technically the same thing, though we use them interchangeably in casual conversation. Mass is the amount of "stuff" in an object. Weight is the force of gravity pulling on that stuff.

If you take your density and volume calculations to the Moon, the mass stays exactly the same. The weight, however, would be much lower. When we talk about finding mass given density and volume in a scientific context, we are talking about that intrinsic property of the object that doesn't change regardless of where it is in the universe.

👉 See also: Why a Closeup of the Moon Still Blows Our Minds

Actionable Next Steps for Accurate Calculation

If you're working on a project right now, don't just grab the first density value you see on Wikipedia.

- Verify the Material: Different alloys of aluminum or types of wood have vastly different densities. "Oak" isn't a specific enough density; is it Red Oak or White Oak?

- Use a Precise Volume: For irregular objects, use the water displacement method. Submerge the item in a graduated cylinder and see how much the water level rises. That rise is your volume.

- Check Your Tooling: If you are using a digital scale to verify your results, ensure it is calibrated.

Basically, the math is the easy part. The data entry—getting the right density and the right volume—is where the "expert" work happens. Double-check your units, multiply the values, and you'll have your mass in seconds.