If you open up a standard web map and look at the top of the African continent, you’re probably seeing a lie. It’s not a malicious one, but it's a lie nonetheless. Seeing north africa on map projections like the Mercator—the one Google Maps and most school atlases use—tends to shrink the actual landmass while inflating the size of Europe and North America. It’s a quirk of geometry. Because you can't flatten a sphere onto a piece of paper without stretching the parts near the poles, the massive stretch of the Sahara ends up looking much smaller than it actually is.

Think about this. Algeria alone is the largest country in Africa. It’s bigger than the entire European Union combined in terms of land area. Yet, on your screen right now, it probably looks roughly the size of a few mid-western US states.

When we talk about the geography here, we aren't just looking at a yellow-and-brown smudge on a screen. We’re talking about a region that bridges the Mediterranean and the deep interior of the world’s second-largest continent. It’s a place defined by the Maghreb in the west and the Nile Valley in the east. It’s huge. It’s complicated. And honestly, it’s one of the most misunderstood strips of land on the planet.

The Mercator Problem and the Reality of Scale

Most people searching for north africa on map coordinates are trying to visualize where Morocco ends and Libya begins, but they rarely grasp the sheer distance involved. If you were to drive from Casablanca to Cairo, you’d be covering over 4,500 kilometers. That is roughly the distance from New York City to Los Angeles.

Why does the map look so "off" to us?

💡 You might also like: Chicago O'Hare Airport Map American Airlines: What Most People Get Wrong

Gerardus Mercator designed his map in 1569 for sailors. It preserved straight lines for navigation (rhumb lines), which was great for not hitting rocks in the 16th century, but it absolutely butchers the scale of anything near the equator. Africa sits right on that equator. Consequently, it looks "squashed" compared to Greenland, which appears nearly the same size on a map but is actually fourteen times smaller than Africa.

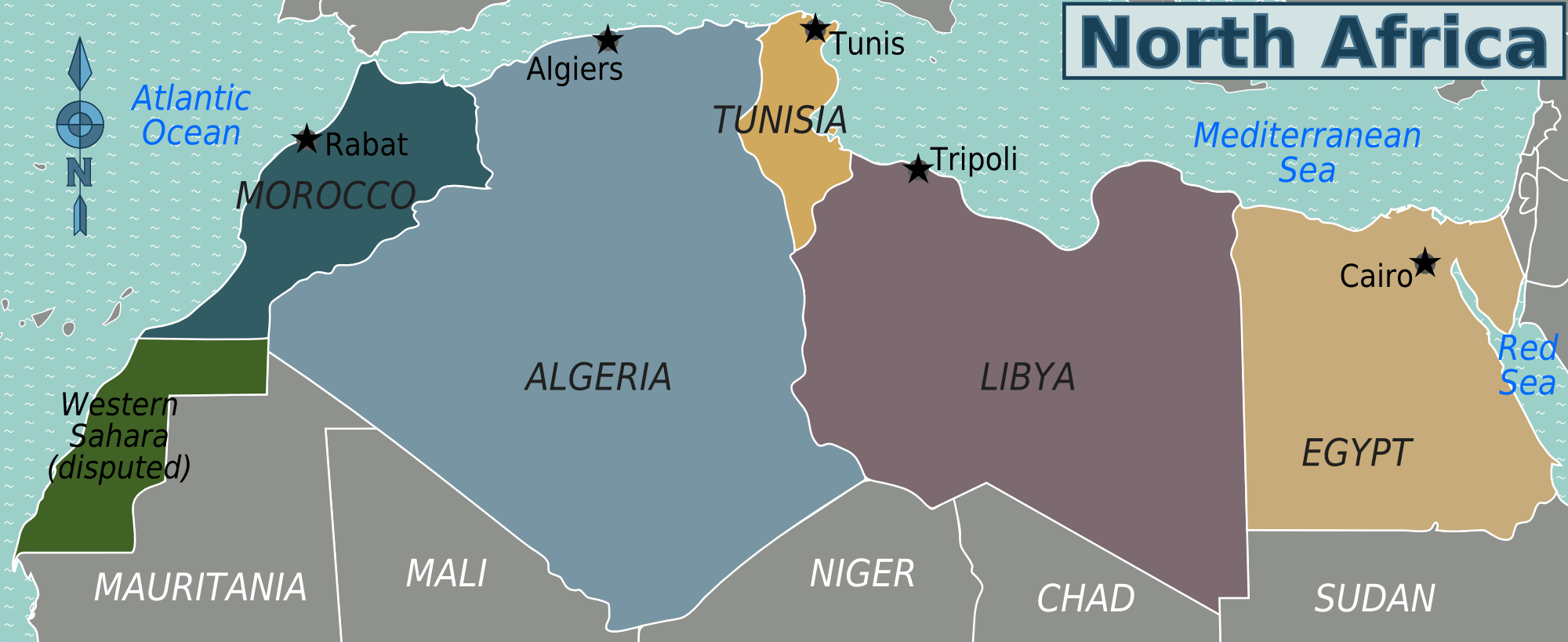

To get a real sense of North Africa, you have to look at the Gall-Peters projection or, better yet, a digital globe like Google Earth. When you spin that globe, you realize that the northern slice of this continent—comprising Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt—is a massive geopolitical powerhouse that acts as the gateway between the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Red Sea.

The Five Pillars: Defining the Region’s Borders

Typically, when a geographer points to north africa on map datasets, they are focusing on five specific nations. Occasionally, Sudan and Western Sahara are pulled into the mix, but the "Big Five" are the historical and cultural core.

Egypt: The Northeast Anchor

Egypt is the bridge. It’s the only country that sits in both Africa and Asia (via the Sinai Peninsula). When you look at it on a satellite map, the most striking thing isn't the desert; it's the thin, neon-green vein of the Nile. 95% of the population lives within a few miles of that water. It’s a vertical country in a horizontal world.

Libya: The Great Void

Libya is massive and mostly empty. On a map, it looks like a giant square. It has the longest Mediterranean coastline of any North African country, but the vast majority of its land is the "Sea of Sand." It’s a country defined by oil and ancient Roman ruins like Leptis Magna, which sit right on the coast, literally crumbling into the sea.

Tunisia: The Green Tip

Tunisia is the smallest, but it’s strategically placed right in the center. It’s the closest point to Sicily. In fact, if you stand on the coast of Kelibia on a clear day, you can almost feel the presence of Europe. It’s more Mediterranean than "desert" in its northern reaches.

Algeria: The Giant

As mentioned, Algeria is the heavyweight. Most people don’t realize that the northern part of Algeria is lush and mountainous (the Tell Atlas), while the southern 80% is the heart of the Sahara. Mapping Algeria is essentially mapping the extremes of the Earth.

📖 Related: Miami Beach Ten Day Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong

Morocco: The Atlantic Gatekeeper

Morocco is unique because it’s the only one with both a Mediterranean and an Atlantic coastline. It’s separated from Spain by only 14 kilometers at the Strait of Gibraltar. On a map, Morocco looks like the "shoulder" of Africa, holding back the Atlantic.

The Sahara Isn't Just "Empty Space"

One of the biggest mistakes people make when looking at north africa on map views is assuming the beige parts are "nothing."

The Sahara is roughly 3.6 million square miles. That is almost exactly the size of the United States.

It’s not just sand dunes (ergs). In fact, sand only covers about 25% of the Sahara. The rest is hamada (barren rocky plateaus), mountain ranges like the Ahaggar in Algeria, and massive salt flats. When you look at a topographic map, you see that North Africa isn't flat. The Atlas Mountains run like a spine through Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, reaching heights of over 4,000 meters at Jbel Toubkal. These mountains are vital because they trap moisture from the Atlantic, creating the fertile plains that have fed empires since the days of Carthage.

Why the "Trans-Saharan" Routes Matter More Than Ever

In 2026, the way we map this region is shifting from physical geography to infrastructure. There’s a massive push for the Trans-Saharan Highway, a project designed to link Algiers on the Mediterranean with Lagos in Nigeria.

Mapping this road tells a story of modern North Africa. It’s no longer just a barrier; it’s a corridor. Fiber optic cables are being laid beneath the sand. Solar farms in the Moroccan desert (like the Noor Ouarzazate complex) are now visible from space, appearing as giant, shimmering blue geometric shapes on the map. These are the new landmarks.

If you look at a map of North Africa from thirty years ago, it looked like a series of isolated coastal cities. Today, the "connectivity map" shows a different story—one of energy pipelines and high-speed rail projects in Morocco that are dragging the interior of the continent into the global economy.

The Geopolitical Map: Water and Borders

Maps aren't just about dirt and water; they’re about power. Two major "clash points" are currently visible if you know where to look.

- The Nile Dispute: Egypt and Sudan are constantly watching the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) further south. On a map, you can see how Egypt is at the "end of the tap." Any map of North African security has to include the flow of the Nile.

- Western Sahara: If you look at a map produced in Morocco, Western Sahara is part of their territory. If you look at one produced by the UN, there’s often a dotted line. Mapping this region is a political act. The "Berm," a 2,700km long sand wall, is one of the longest military structures on earth, yet it’s rarely featured on standard consumer maps.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you are planning a trip, or just trying to understand world news, stop looking at flat 2D Mercator maps. They distort your sense of reality.

First, get a globe app. Spin it. See how Africa dwarfs Europe.

Second, look at "Human Density" maps. You’ll see that North Africa is essentially a "coastal fringe" civilization where the vast majority of life happens within 100 miles of the sea, except for the long ribbon of the Nile.

Third, check the "Relief Map." Understand that the Atlas Mountains are the reason Morocco is green and Libya is not.

Understanding the map of North Africa is about realizing that the desert isn't a wall—it's a bridge that has been crossed by salt caravans, armies, and now data packets for thousands of years. The scale is the story.

Next Steps for Navigating North Africa Research

📖 Related: Delta Flight to Atlanta Today Status: How to Not Get Stranded at Hartsfield-Jackson

To get a truly accurate sense of the region beyond a basic screen grab, your next step should be to explore the Nile Basin Initiative maps to see how water rights are reshaping the east, or use the World Bank’s Infrastructure Tracker to see where the Trans-Saharan Highway currently stands. If you’re traveling, ignore the "straight-line" distances on a map; always calculate travel time based on the Atlas Mountain topography, as a 100-mile drive in Morocco can take five hours due to the elevation changes you can't see on a flat projection.