You’ve seen them in movies. You’ve probably heard about them in some weird Taoist legend or a martial arts novel. But if you actually try to find the Kunlun Mountains on a map, it's a bit of a headache. Most people just point a finger at the top of the Tibetan Plateau and call it a day. That's a mistake. Honestly, the Kunlun range is a massive, sprawling beast that stretches over 1,200 miles, and it doesn't look like the neat little line you see on a school globe.

It's huge.

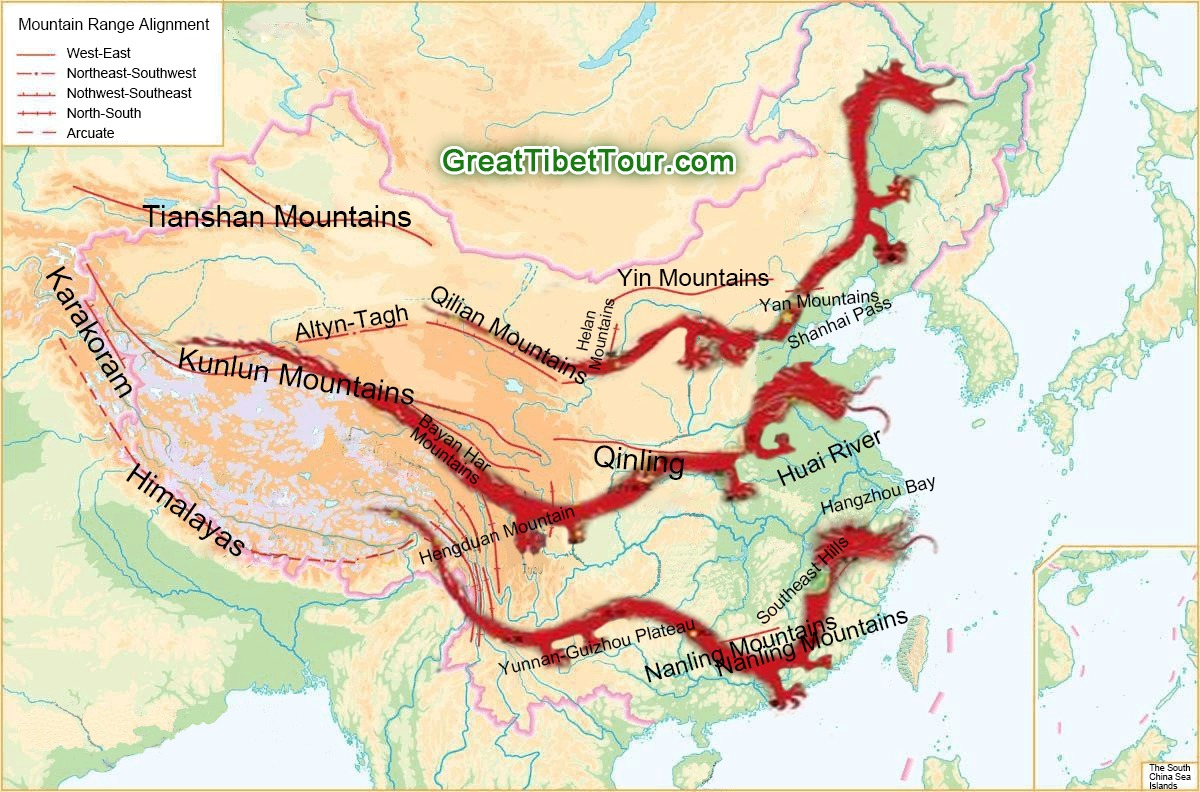

When you look at a topographical map of Central Asia, the Kunlun Mountains form the literal backbone of the continent. They act as the northern "retaining wall" for the Tibetan Plateau. South of them, you have the highest flatland on Earth. North of them? The Taklamakan Desert, a place so dry and brutal that its name basically translates to "you go in, but you don't come out."

👉 See also: How Far Is Wisconsin From Me: Your Practical Guide to Getting There

Why the Kunlun Mountains on a Map Look Different Than You Expect

Geology is messy. If you're looking for the Kunlun range, you have to start where the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan end. They kick off in the west and march straight across China, separating the Xinjiang Autonomous Region from Tibet. But here is the thing: they aren't just one ridge. They are a complex system of parallel chains.

If you zoom in on a digital map, look for the Keriya Pass or the Kunlun Pass. These are the places where human history actually managed to punch through the rock. For centuries, traders on the Silk Road looked at the Kunlun on their maps—or their hand-drawn scrolls—and saw a wall of ice. They didn't go over it unless they absolutely had to. They went around it. This is why the southern branch of the Silk Road hugs the northern base of the mountains, moving from oasis to oasis like Hotan and Yarkand.

The elevation is staggering. We are talking about peaks that consistently hit over 20,000 feet. Liushi Shan, often cited as the highest point, reaches 23,501 feet. That’s not a mountain; that’s a skyscraper of granite and permafrost.

The Mythical vs. The Physical Map

We have to talk about the confusion between the real Kunlun and the "Jade Mountain" of legend. In Chinese mythology, the Kunlun Mountains are the home of the Queen Mother of the West. It’s supposed to be a paradise. If you look at a map from the Han Dynasty, "Kunlun" wasn't just a geographical coordinate; it was a spiritual center.

Modern geographers have a bit of a laugh about this because the real Kunlun is anything but a garden. It is a high-altitude desert. It’s rocky, wind-swept, and incredibly lonely. Explorers like Sven Hedin and Aurel Stein spent years trying to map these ridges in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They found that the maps they had were often miles off. They dealt with altitude sickness, freezing gales, and the fact that the mountains just... kept... going.

The range is actually widening. Because the Indian tectonic plate is still slamming into the Eurasian plate, the whole area is being squeezed and lifted. It's a geological car crash happening in slow motion.

Locating the Key Features of the Range

If you want to be precise when identifying the Kunlun Mountains on a map, you should look for three distinct sections.

The Western Kunlun is the most rugged part. This is where the mountains are narrow and incredibly high, bunching up near the Karakoram range. If you find the city of Kashgar and look southeast, you're looking at the start of the Western Kunlun.

The Central Kunlun is where the range starts to spread out. This area contains some of the most remote territory on the planet. The Changtang plateau sits just to the south. This is a place where there are no permanent human settlements for hundreds of miles. Just wild yaks, Tibetan antelopes, and the occasional research station.

Then you have the Eastern Kunlun. This section eventually peters out into the Bayan Har Mountains, which is super important because that is where the Yellow River begins. Imagine that: one of the world's greatest civilizations, China, owes its primary water source to the snowmelt coming off the eastern tail of the Kunlun.

Why Does This Map Placement Matter?

It dictates the climate of an entire continent. The Kunlun Mountains act as a barrier for the monsoons. The wet air coming up from the Indian Ocean hits the Himalayas and the Kunlun, gets rung out like a wet towel, and leaves the land to the north—the Tarim Basin—completely parched. Without the Kunlun, the geography of Asia would be unrecognizable.

You've also got the Qinghai-Tibet Railway. Mapping this was a nightmare for engineers. They had to lay tracks over permafrost that melts and shifts. When you look at a modern transportation map, you’ll see a line snaking through the Kunlun Pass at an elevation of 15,600 feet. It is the highest railway in the world.

The Geological Reality vs. Popular Misconceptions

People often mistake the Kunlun for the Himalayas. They are neighbors, sure, but they are different families. The Himalayas are further south. The Kunlun are older, grittier, and in many ways, more desolate.

Another big mistake? Thinking the Kunlun is just a Chinese mountain range. While the bulk of it is in China, its western roots tangle into the Pamir Knot, which involves Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. It’s a geopolitical crossroads.

- The range isn't just rock; it's a massive storehouse of minerals.

- Gold, jade, and copper are tucked into these folds.

- The "Kunlun Jade" you see in high-end jewelry stores comes from specific quarries in these mountains.

- Mapping these mineral deposits is a high-stakes game for mining companies today.

The sheer scale of the range makes it a "black hole" for GPS in some valleys. Because the terrain is so steep and the valleys are so deep, satellite signals can get wonky. If you're actually out there, you don't just rely on a digital map. You use a topographic paper map and a compass, or you end up lost in a place where the nearest help is a three-day trek away.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Search

If you are trying to study or visualize the Kunlun Mountains, don't just type the name into a search bar and look at the first map that pops up. Those are usually too simplified.

✨ Don't miss: San Luis AZ Cameras: What You Actually Need to Know Before Heading South

First, use a satellite layer. Look for the "white" vs "brown" contrast. The white is the permanent glacial cover on the high peaks like Kongur Tagh (which is technically Pamir but often grouped in). The brown is the high-altitude desert.

Second, track the rivers. Find the Yurungkash (White Jade River) and the Karakash (Black Jade River). Both start in the Kunlun and flow north into the desert. Following these riverbeds on a map is the easiest way to understand the drainage patterns of the range.

Third, look for the G219 highway. It’s one of the most insane roads on the planet. It tracks right through the heart of the Western Kunlun. If you follow that line on your map, you’ll see exactly how the mountains transition from the lush valleys of the south to the desolate high-altitude plains of the north.

Understanding the Kunlun is about understanding the "Third Pole." This isn't just a line on a map; it's a massive thermal engine that drives the weather for billions of people. Next time you see the Kunlun Mountains on a map, don't just see a border. See the wall that shaped the history of the East.