You’d think it would be easy. You look at a globe, find the very top where all those lines of longitude meet, and poke your finger on it. Boom. The North Pole. But honestly, if you’re actually trying to locate the North Pole on a map to, say, navigate a ship or fly a plane, you’re going to run into a massive headache almost immediately. There isn't just one "North Pole." Depending on what kind of map you’re holding and what year it was printed, that little dot at the top of the world might be lying to you.

Maps are flat. The Earth is—mostly—a sphere. This fundamental geometric disagreement means that representing the North Pole on a map involves a lot of "faking it." Mapmakers have been wrestling with this for centuries, from the early days of Gerardus Mercator to the high-tech GPS grids we use today. When you see the North Pole on a standard classroom map, it’s usually stretched out into a long horizontal line across the top, which is technically impossible. It’s a point, not a line. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, literally and figuratively.

Which North Pole are we even talking about?

Most people assume "North" is a fixed destination. It’s not. When you’re looking for the North Pole on a map, you have to decide if you want the Geographic North Pole or the Magnetic North Pole. These are two very different places.

The Geographic North Pole, also known as True North, is the fixed point at $90^\circ\text{N}$ latitude where the Earth’s axis of rotation meets the surface. This is the spot Santa supposedly lives. It doesn't move. If you’re looking at a standard topographic map, this is the point all the vertical lines (meridians) converge toward. It’s the "top" of the world in a mathematical sense.

Then there’s the Magnetic North Pole. This is where your compass actually points. Here’s the kicker: it moves. A lot. Currently, the Magnetic North Pole is trekking away from the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia at a rate of about 34 miles per year. If you take a map from 1990 and try to find the Magnetic North Pole today, you’ll be hundreds of miles off. Scientists from the British Geological Survey and the National Centers for Environmental Information have to update the World Magnetic Model every five years just to keep our smartphone maps from glitching out.

Wait, there’s actually a third one. The Geomagnetic North Pole. This is a theoretical point based on a simplified model of the Earth’s magnetic field, acting like a giant bar magnet stuck in the center of the planet. It’s used by researchers studying the magnetosphere and the aurora borealis. So, if you’re a traveler or a scientist, "the North Pole" is a moving target.

The Mercator problem and why the Pole looks huge

Ever noticed how Greenland looks as big as Africa on some maps? That’s the Mercator projection. It was designed in 1569 for sailors, and while it’s great for plotting a straight course across the ocean, it’s absolutely terrible for representing the North Pole.

On a Mercator map, the North Pole technically doesn't exist. The math required to flatten the globe onto a cylinder means that as you get closer to the poles, the map stretches to infinity. To make the map usable, cartographers usually just chop off the top and bottom. The North Pole becomes an unreachable line at the very edge of the page. This distortion is why the Arctic looks like a massive, sprawling continent of ice on your screen, when in reality, it’s an ocean surrounded by land.

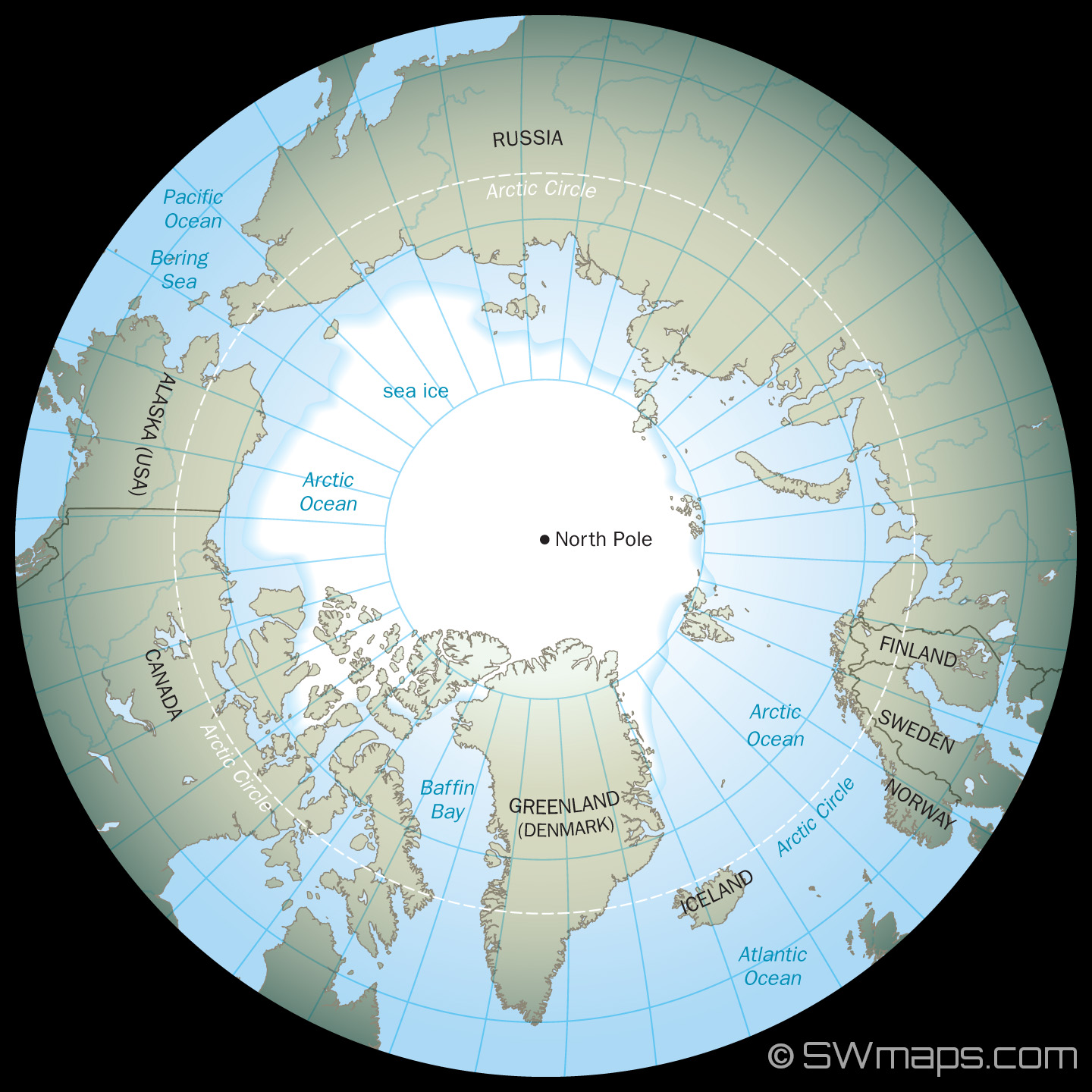

If you want to see the North Pole on a map that actually makes sense, you need a Polar Projection (or Azimuthal Equidistant projection). This map looks like a circle with the North Pole right in the center. It’s the view you see on the United Nations flag. From this perspective, every direction away from the center is South. It’s the only way to visualize the Arctic Basin without the "Greenland is huge" lie.

Mapping a place with no land

One of the weirdest things about locating the North Pole on a map is that there is nothing solid there. Unlike the South Pole, which sits on the massive continent of Antarctica (covered by about 9,000 feet of ice), the North Pole is just floating sea ice.

- The water beneath the ice is about 13,400 feet deep.

- The ice itself is usually only 6 to 10 feet thick.

- It is constantly drifting.

If you were to plant a flag at the Geographic North Pole today, by tomorrow morning, that flag would have moved several hundred yards because the ice pack is always in motion. This makes mapping the "surface" of the North Pole impossible in the traditional sense. You can map the seafloor—which the Russians did in 2007 when they famously dropped a titanium flag on the seabed using a Mir submersible—but you can’t map a permanent "spot" on the surface.

Why the North Pole on a map is a geopolitical mess

Mapping the North Pole isn't just about geography; it’s about power and money. Because the ice is melting due to climate change, new shipping routes are opening up, and everyone wants a piece of the pie.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) allows countries to claim territory if they can prove their continental shelf extends under the Arctic Ocean. This has led to a "Map War." Russia, Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), and Norway have all submitted overlapping claims to the North Pole. Russia argues that the Lomonosov Ridge—an underwater mountain range—is an extension of their territory. Denmark argues it’s an extension of Greenland.

💡 You might also like: Capo Bay Hotel Cyprus: Why It Stays the Best Spot in Protaras Without Even Trying

When you look at a modern political map of the Arctic, you’ll see dotted lines and "Exclusive Economic Zones" (EEZs). The North Pole currently sits in international waters, but if you look at a map produced by the Russian government, the lines might look a bit different than a map produced in Ottawa. Mapping this region is a high-stakes game of "who owns the bottom of the ocean."

The "Great Void" in early cartography

Historically, maps of the North Pole were pure fantasy. For centuries, cartographers didn't know what was up there, so they just made stuff up. A famous 16th-century map by Gerardus Mercator shows a massive black rock called the Rupes Nigra (the Black Rock) sitting right at the pole, surrounded by a giant whirlpool and four large islands.

People genuinely believed this rock was what made compasses point North. It wasn't until explorers like Fridtjof Nansen and later Robert Peary (whose claim to have reached the pole is still hotly debated by historians) actually went there that we realized the "top of the world" was just a lot of cold, shifting water.

How to find the North Pole on a map today

If you’re using a digital map like Google Maps or Apple Maps, you’ll notice they’ve mostly moved away from the flat Mercator view when you zoom out. They use a 3D globe. This is the most "honest" way to see the North Pole.

- Open your map app and zoom out as far as possible until you see the Earth as a sphere.

- Swipe "down" until the top of the planet is facing you.

- You’ll see a vast expanse of white. This is the Arctic ice pack.

- The Geographic North Pole is the center of the convergence of all the faint blue lines of longitude.

But even this is a bit of an illusion. The white area you see on Google Maps isn't a live satellite photo. It's a stylized representation. Satellite imagery of the North Pole is actually quite difficult to get in a "seamless" way because most satellites orbit in a way that doesn't pass directly over the 90-degree mark, creating what’s known as the "Pole Hole" in satellite data.

👉 See also: Lewis and Clark Landing Omaha NE: What Really Happened at the White Catfish Camp

Practical Insights for the Modern Explorer

Mapping the North Pole has changed from a quest for discovery to a technical challenge of precision. If you are actually planning to navigate near the top of the world, here is what you need to know.

First, your standard GPS will work, but your magnetic compass will become increasingly useless as you get closer to the Magnetic North Pole. The needle will try to point "down" into the Earth rather than horizontally toward a destination. This is called "inclination" or "magnetic dip."

Second, understand that "North" on your map is a calculation, not a physical reality. Most digital maps use the WGS 84 (World Geodetic System 1984) coordinate system. This is the "map" that your phone uses to tell you where you are. It treats the Earth as an ellipsoid. When you find the North Pole on a WGS 84 map, you are finding a mathematical coordinate ($90.0000^\circ\text{N}$, $0.0000^\circ\text{E}$), not necessarily a "place" you can stand on forever.

If you’re a hobbyist or just curious, the best way to "see" the North Pole is to look for bathymetric maps. These show the ridges and valleys of the ocean floor. That’s the only part of the North Pole that stays still long enough to be drawn accurately. The surface is just a moving puzzle of ice and water, forever defying our attempts to pin it down on paper.

To get the most accurate view of the North Pole, check out the International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO). It's the gold standard for what's actually happening at the top of our world. Whether you're interested in the "where" for travel or the "why" for science, remember that the North Pole on a map is always a compromise between reality and geometry.

Next time you see that little red pin at the top of a digital map, remember there's about 13,000 feet of water, a shifting ice floe, and a whole lot of international legal drama sitting right underneath it.