Rhyme is weird. We learn it in kindergarten with "The Cat in the Hat" and then, for some reason, a lot of people spend the rest of their lives thinking that if a poem doesn't rhyme, it’s just a broken sentence. Or worse, they think every example of a poem that rhymes has to be about a dog on a log or a frog in a fog. It doesn't. Honestly, rhyme is a high-wire act. If you do it perfectly, the reader doesn't even notice the "click" of the matching sounds. If you do it poorly, it sounds like a jingle for a local car dealership.

Most people searching for a rhyming poem are looking for that specific satisfying snap. It’s called "phonemic awareness" in the academic world, but for the rest of us, it’s just the brain liking patterns. When you find a solid example of a poem that rhymes, you aren't just looking at words that sound the same; you’re looking at a structured architecture of sound.

Why We Crave the Rhyme

Structure matters. Robert Frost once famously said that writing free verse (poetry without rhyme or meter) was like playing tennis without a net. He wanted the resistance. He wanted the rules. For Frost, a rhyming poem wasn't a restriction; it was a challenge to find the exact right word that fit both the meaning and the melody.

Take a look at his classic, "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." It’s probably the most famous example of a poem that rhymes in the English language.

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

Notice the "know," "though," and "snow." It’s an AABA rhyme scheme. But here’s the kicker: the third line ("here") doesn't rhyme with the others in that stanza. Instead, it sets up the rhyme for the next stanza. That’s called a chain rhyme. It pulls the reader through the poem like a thread through a needle. It’s genius because it feels natural. You don’t feel like Frost was flipping through a rhyming dictionary sweating bullets.

The Difference Between Perfect and Slant Rhyme

You've probably heard rhymes that feel... off. Like "orange" and "door hinge." (Thanks, Eminem). In the world of poetry, we distinguish between "perfect" rhymes and "slant" rhymes.

A perfect rhyme is exactly what it sounds like: cat and hat. Light and bright. These are the bread and butter of traditional verse. But if you use too many of them, the poem starts to sound "sing-songy." It gets predictable. You know exactly what’s coming next, and that’s when the reader’s brain checks out.

Slant rhyme—also called half rhyme or near rhyme—is the cool, younger sibling of perfect rhyme. Think of Emily Dickinson. She was the queen of the slant rhyme. She’d pair "soul" with "all" or "bridge" with "grudge." It’s just close enough to satisfy the ear but different enough to keep you on your toes.

Basically, slant rhymes give a poem a modern, edgy feel. If you’re trying to write your own, don't feel like you have to be perfect. Sometimes the "almost" rhyme is more powerful because it creates a sense of tension or unease.

Digging Into Sonnets: The Heavyweights of Rhyme

If you want a classic example of a poem that rhymes, you have to talk about sonnets. Shakespeare didn't invent them, but he definitely owned them. A Shakespearean sonnet has a very specific "recipe": 14 lines, iambic pentameter (that da-DUM da-DUM heartbeat rhythm), and a rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

That final "GG"—the rhyming couplet at the end—is where the magic happens.

📖 Related: Why In The End by Black Veil Brides Lyrics Still Hit Hard After a Decade

- Line 1: A

- Line 2: B

- Line 3: A

- Line 4: B

And so on. When you get to the very end, those last two lines rhyme with each other. It’s like a punchline. Or a summary. In Sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?"), the whole poem argues that the subject’s beauty will last forever because the poem itself will last forever.

The final couplet:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

It’s satisfying. It’s definitive. It’s also incredibly hard to write without sounding like you’re trying too hard.

Common Misconceptions About Rhyming Poetry

People think rhyming is for kids. They think it’s "easy" poetry.

Actually, it's the opposite. It is much harder to write a good rhyming poem than it is to write a mediocre free verse poem. Why? Because you’re fighting the language. English is a "rhyme-poor" language compared to Italian or French. In Italian, almost every word ends in a vowel, so rhyming is like shooting fish in a barrel. In English, we have a lot of "clunky" consonants.

When you see a great example of a poem that rhymes, look at the word choice. Is the poet using the word "love" and then immediately following it with "dove" or "above"? If so, they’re taking the easy way out. Great poets look for the unexpected. They want to surprise you.

Modern Rhyme: Hip-Hop and Spoken Word

If you think rhyming poetry died with the Victorians, you haven't been paying attention to music. Rap is arguably the most vibrant form of rhyming poetry we have today.

Look at someone like Kendrick Lamar or MF DOOM. They don't just rhyme the last word of every line. They use "internal rhyme," where words inside the line rhyme with each other. They use "multisyllabic rhymes," where whole phrases mirror the sound of other phrases.

"The shoelace is loose, the juice is in the goose." (Okay, I made that up, it's terrible).

But a real lyricist would do something like:

"The patter of the matter made the clatter seem flatter."

It creates a percussive effect. It’s rhythmic. It’s visceral. When you’re looking for a contemporary example of a poem that rhymes, don’t just look in dusty old books. Look at the lyrics of artists who are obsessed with the "feel" of words in the mouth.

Identifying Different Rhyme Schemes

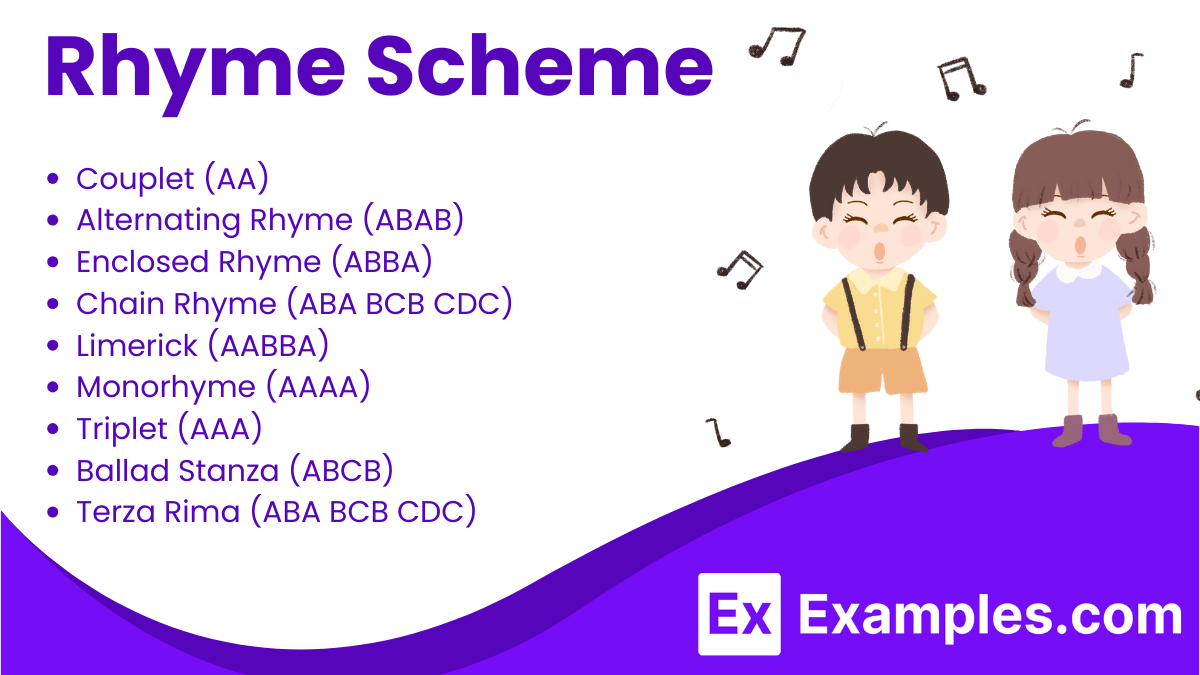

You've got your AABB (the couplet style). You've got your ABAB (alternate rhyme). Then you've got the weird stuff like the Limerick (AABBA), which is almost always used for dirty jokes or nonsense.

The AABB scheme is often found in nursery rhymes or simple ballads.

The cat sat on the mat. (A)

He wore a tiny hat. (A)

He looked at the blue sky. (B)

And started to cry. (B)

It’s very "drum-heavy." It hits the beat hard.

Then you have the "Enclosed Rhyme" (ABBA). This is where the first and fourth lines rhyme, "hugging" the middle two lines. It feels more contained, more thoughtful.

Practical Tips for Writing Rhyming Verse

If you're trying to craft your own example of a poem that rhymes, stop using a rhyming dictionary as your first step. It makes the poem feel hollow.

Write the line you want to write first. Focus on the meaning. What are you actually trying to say? Once you have that "anchor" line, look at the last word. Is it a word that has a lot of rhyming partners? Words like "life," "night," or "heart" are easy to rhyme but also very "cliché."

Try ending a line with a word that’s a bit more specific. "Amethyst." "Concrete." "Linger."

Once you have your end-word, think about the rhythm. If your first line has ten syllables and your second line has four, the rhyme is going to feel like a car hitting a pothole. You need a consistent meter to make the rhyme land effectively.

Notable Examples to Study

If you want to see how the pros do it, check out these specific works.

✨ Don't miss: Crazy Little Thing Called Love Lyrics: The 10-Minute Bathroom Miracle That Saved Queen

- Edgar Allan Poe, "The Raven": This is a masterclass in internal rhyme and alliteration. "Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary." The "dreary/weary" rhyme happens within the line. It creates a hypnotic, almost haunting effect.

- Maya Angelou, "Still I Rise": She uses rhyme to create a sense of defiance and rhythm. It feels like a march. The rhymes are strong and clear, which mirrors the strength of the message.

- Lewis Carroll, "Jabberwocky": This proves you don't even need real words to make a rhyming poem work. The structure and the sounds carry the meaning even when the words are made up.

The Wrap-Up on Rhyme

Rhyme is a tool, not a requirement. It can make a poem memorable, funny, or heartbreaking. But it has to be handled with care. If the rhyme is driving the poem, the poem is usually bad. The meaning should drive the poem, and the rhyme should just be the music that plays in the background.

Honestly, the best way to get better at spotting a good example of a poem that rhymes is to read them out loud. Your ears are much better judges of rhyme than your eyes. If you stumble over a word, or if the rhyme feels forced and "cringey," then the poet failed. If it flows like water, you've found a winner.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Rhyme

- Read "The Raven" out loud. Pay attention to where the rhymes happen—not just at the ends of the lines, but in the middle.

- Listen to a rap track without the music. Read the lyrics as a poem. Look for multisyllabic rhymes (rhyming three or four syllables at a time) rather than just single-syllable endings.

- Practice "Slant Rhyming." Write five pairs of words that almost rhyme but not quite (like bridge and grudge). Notice how much more "modern" they feel than cat and hat.

- Identify the scheme. Take any poem you find and label the end of each line with letters (A, B, C) to see the pattern. It’s like decoding a secret message.

- Check the meter. Clap along to the rhythm of a rhyming poem. If the claps don't line up with the rhymes, the poem will likely feel "clunky" to a reader.