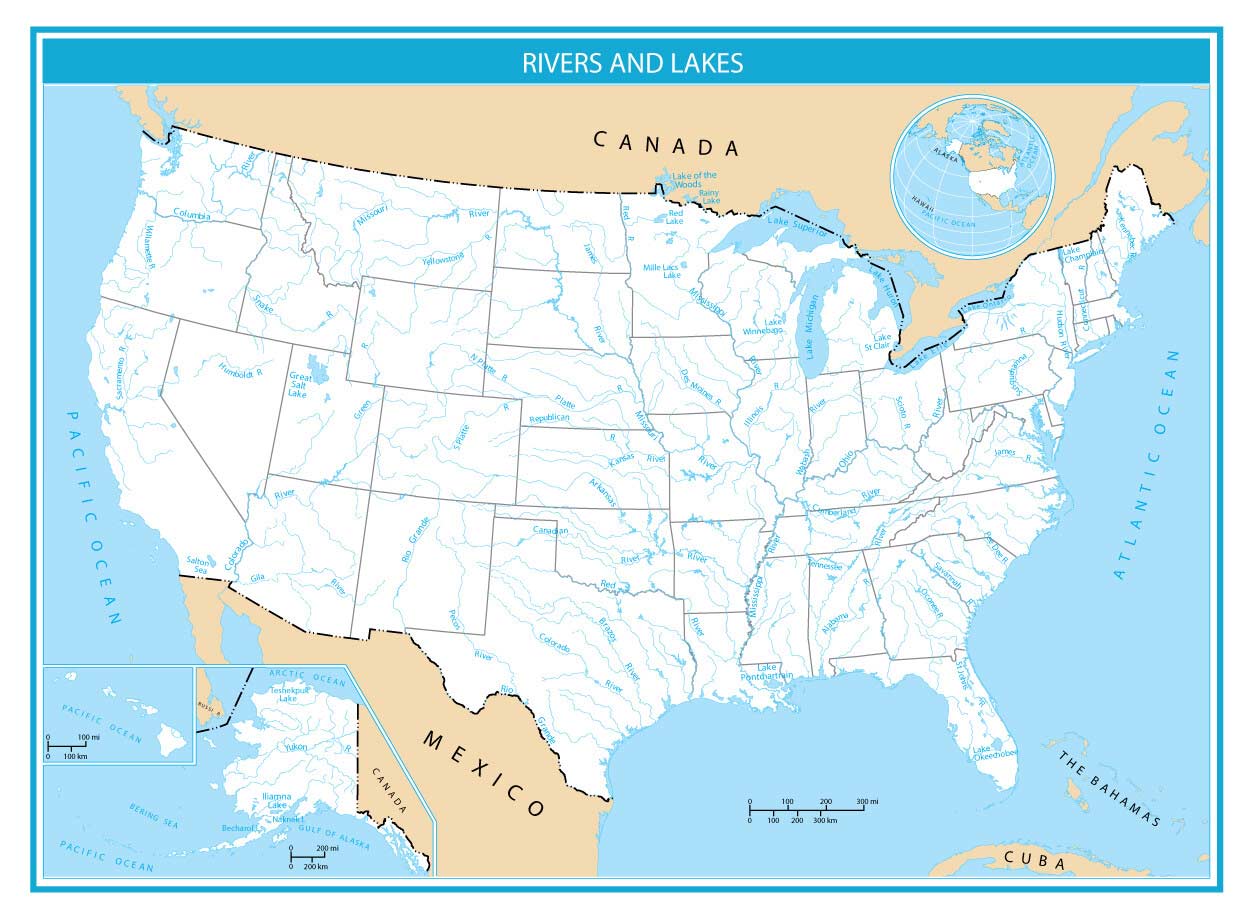

You’ve probably stared at one in a classroom or on a rest stop wall. A map of the United States with bodies of water looks like a giant blue circulatory system. It’s messy. It’s intricate. Most people just see a big splash of blue on the left, another on the right, and maybe those five giant blobs up north. But if you actually look closer, those blue lines and shapes tell the real story of how this country was built, where we drink from, and why certain cities even exist.

Water dictated everything.

Take a second to think about why St. Louis is where it is. It isn't random. It’s right there where the Missouri and Mississippi rivers shake hands. Without that specific blue line on the map, the "Gateway to the West" would just be another patch of prairie. We often treat these maps as static decorations, but they are actually blueprints of survival and commerce.

Why a Map of the United States with Bodies of Water is Never Just "Finished"

Cartography is a bit of a lie. Well, a temporary truth, anyway. If you look at a map of the United States with bodies of water from 1920 versus one from 2026, things have shifted. Not just because of climate change—though that’s a huge part of it—but because humans are obsessed with moving water around.

Lake Mead and Lake Powell are perfect examples. These aren't natural features. They are massive puddles we made by damming the Colorado River. On a map, they look like permanent fixtures of the American Southwest. In reality, they are fluctuating reservoirs that reveal sunken ghost towns when the water gets low.

Rivers move too. The Mississippi River is basically a giant, wet snake that wants to wiggle toward the Atchafalaya Basin. The only reason the map looks the same every year is because the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spends billions of dollars to keep that blue line exactly where it is. If they stopped? The map would rewrite itself in a single flood season.

The Big Players: Oceans and Gulfs

We have to start with the borders. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans define our coasts, obviously. But the Gulf of Mexico is the underrated MVP. It’s warmer. It’s shallower. It fuels the hurricanes that reshape the coastline of Louisiana and Florida every decade.

When you look at the jagged edges of the East Coast, you're seeing the result of thousands of years of rising sea levels drowning river valleys. That's what Chesapeake Bay is—a "ria" or a drowned river valley. It’s one of the most complex features on any map of the United States with bodies of water because it’s neither fully river nor fully ocean. It’s brackish, moody, and vital for the local economy.

💡 You might also like: Train to Soller Majorca: Why Most Tourists Get the Timing Wrong

The Great Lakes: America’s Fourth Coast

Honestly, calling them "lakes" feels like an insult. Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario hold about 21% of the world's surface fresh water. That is an insane statistic. If you stood on the shore of Lake Superior, you wouldn't see the other side. You'd see waves big enough to sink the Edmund Fitzgerald, a 729-foot freighter.

These bodies of water are the reason the Midwest became an industrial powerhouse. The Saint Lawrence Seaway connects these inland "seas" to the Atlantic Ocean. This means a ship can pick up grain in Duluth, Minnesota, and sail it all the way to Liverpool, England.

- Lake Superior: The largest, deepest, and coldest. It contains more water than all the other Great Lakes combined, plus three extra Lake Eries.

- Lake Michigan: The only one entirely within U.S. borders. Chicago basically owes its existence to this giant pool of blue.

- Lake Erie: The shallowest. Because it’s shallow, it warms up the fastest in the summer and freezes the easiest in the winter. It’s also the most sensitive to pollution.

The River Systems Most People Forget

Everyone knows the Mississippi. It’s the "Father of Waters." It drains 31 states and two Canadian provinces. But have you ever looked at the Ohio River on a map? It’s arguably more important for the history of American expansion.

The Ohio starts in Pittsburgh where the Allegheny and Monongahela meet. It flows through the heart of the rust belt. For a long time, it was the "highway" for settlers moving west. On a map of the United States with bodies of water, the Ohio acts as a heavy blue border between the North and the South.

Then there’s the Missouri River. It’s actually longer than the Mississippi. If you measured the Missouri-Mississippi system as one continuous flow, it would be the fourth-longest river in the world. It’s nicknamed "Big Muddy" because of the sheer amount of silt it carries from the Great Plains.

The Great Basin: Where Water Goes to Die

This is the weirdest part of the map. In most of the U.S., if a raindrop hits the ground, it eventually finds its way to the ocean. In the Great Basin—covering most of Nevada and parts of Utah, Oregon, and California—the water just... stops.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Black Sea on Map of Europe: Why This Giant Basin is Turning Into a Global Hotspot

There is no outlet to the sea.

The Humboldt River in Nevada is a great example. It just flows into the desert and evaporates or sinks into the ground. The Great Salt Lake is the most famous remnant of this "endorheic" drainage. Because the water can't leave, minerals and salts build up. It's basically a giant, salty puddle that's shrinking every year, leaving behind toxic dust.

Understanding the "Alphabet Soup" of Inland Waters

If you're looking at a high-quality map of the United States with bodies of water, you'll notice names that sound more like descriptions. Sounds, bayous, bights, and lagoons.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina are separated from the mainland by sounds like Pamlico and Albemarle. These are shallow, protected waters that are world-class nurseries for fish. Down in Louisiana, the map turns into a lace-like pattern of bayous. A bayou is basically a slow-moving or stagnant stream. It's water that isn't in a hurry to get anywhere.

In the Pacific Northwest, you have the Puget Sound. It's a deep, glacial fjord system. It looks nothing like the flat, sandy lagoons of the Gulf Coast. The water there is deep, cold, and carved by ice.

The Disappearing Act: Water Scarcity and the Map

We need to talk about the Rio Grande. On a standard map, it’s a bold blue line marking the border between Texas and Mexico. In reality? Large stretches of it are bone-dry for much of the year.

Years of heavy irrigation and drought have turned one of North America’s great rivers into a series of disconnected puddles in certain seasons. The Colorado River is in a similar boat. It’s so heavily used by cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles that it rarely reaches its natural delta in the Gulf of California.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Porto in Portugal Map Experts Actually Use

When you see these rivers on a map of the United States with bodies of water, remember that you're looking at a "potential" river, not necessarily a flowing one.

Practical Ways to Use This Information

Whether you're a hiker, a student, or someone just trying to understand where your taxes go, knowing these waterways matters. It helps you understand flood risks. It explains why your electricity bill might be lower (thank you, hydroelectric dams).

- Check Watershed Maps: Instead of just looking at the rivers, look at the watersheds. A watershed map shows you which river your local rain flows into. This tells you exactly where your local pollution ends up.

- Compare Historical Maps: Use tools like the USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer to see how bodies of water have changed over the last century. You'll see islands that disappeared and reservoirs that didn't exist 50 years ago.

- Identify "Dead Zones": Research the Gulf of Mexico's "Dead Zone." This is a massive area of low oxygen caused by nutrient runoff from the Mississippi River. It’s a direct link between the heartland’s farms and the ocean’s health.

- Local Exploration: Find the nearest "blue line" on your local map. Follow it. Most of our modern infrastructure hides water in concrete pipes, but it’s always there, trying to find the lowest point.

The United States isn't just a collection of 50 states. It's a collection of watersheds. Every major city, every farm, and every power plant is tethered to the blue lines on that map. Without them, the rest of the map—the roads, the borders, the cities—simply wouldn't exist.

Next time you look at a map, don't just look for the names of the states. Look at the water. It’s the only part of the map that’s actually alive.

To get a better sense of how these waterways impact your specific region, look up your local "HUC" (Hydrologic Unit Code). This is the professional way geologists and environmental scientists categorize every square inch of the country based on where the water flows. Understanding your local HUC is the first step in becoming a better steward of your local environment and understanding the real-world implications of the lines on the map.