Maps are weirdly deceptive. You look at a standard mountain ranges in europe map and it looks like a bunch of brown crinkles scattered across a green background, but those crinkles are the reason Spain feels nothing like France and why the Swiss have four national languages. It’s not just about geology. It’s about how these massive piles of rock have funneled human history, migration, and even the weather for thousands of years.

Europe is essentially a giant peninsula, but it's a peninsula with a spine that’s been broken and reset in a dozen different directions.

If you’re planning a trip or just trying to win a pub quiz, you’ve gotta realize that "mountains" in Europe aren't a monolith. You have the young, jagged, "look at me" peaks of the Alps, and then you have the ancient, eroded, "I've seen it all" stumps of the Urals. They are totally different vibes. Honestly, if you just follow the map blindly without understanding the terrain, you’re going to end up stuck behind a tractor on a 12% grade in the Pyrenees wondering where it all went wrong.

The Alps: Not Just for Skiing and Chocolate

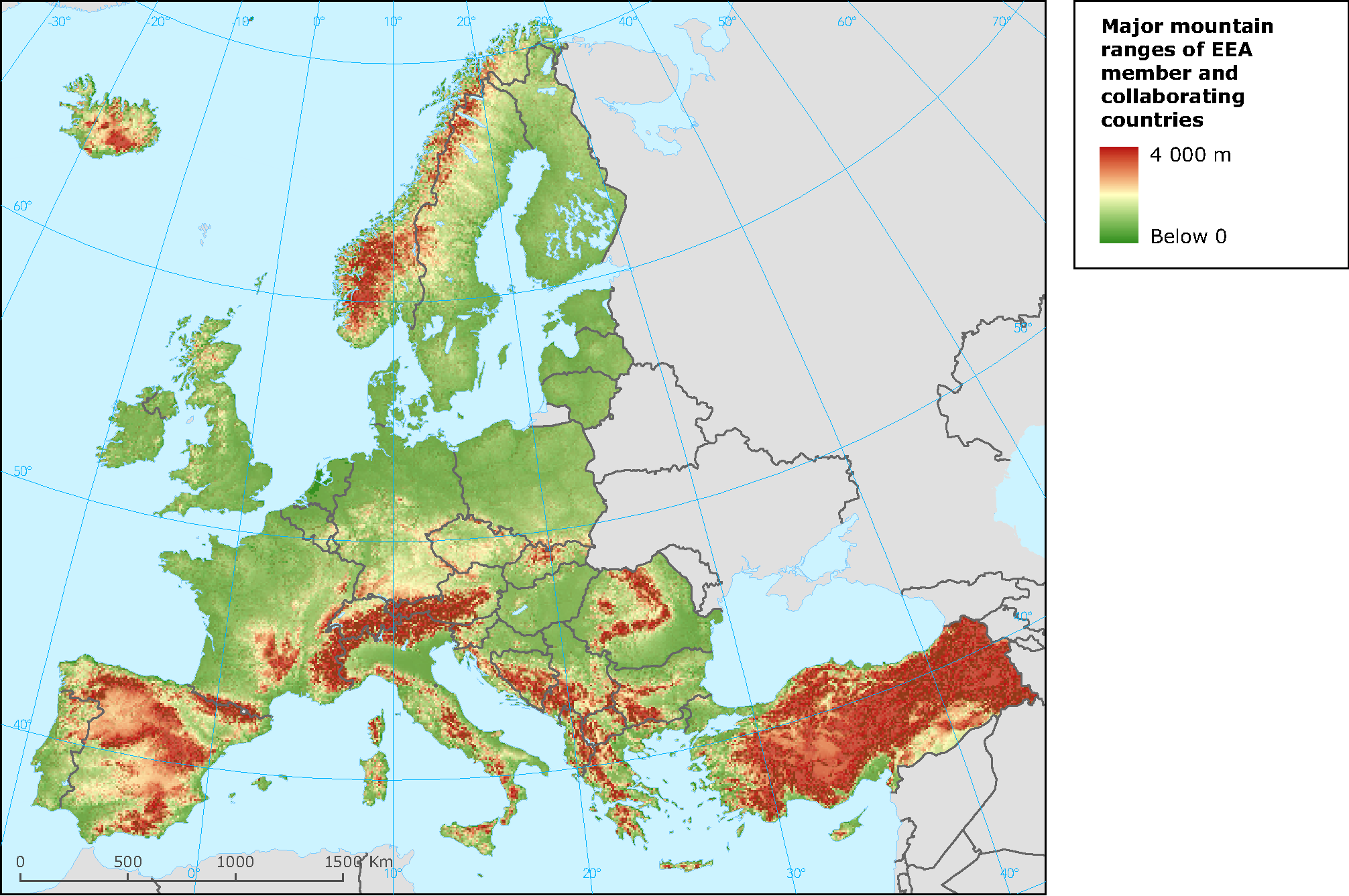

When people search for a mountain ranges in europe map, the first thing their eyes dart to is that big arc in the middle. The Alps. They’re the superstars. Stretching across eight countries—France, Switzerland, Monaco, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia—they basically dominate the central European climate.

They’re young. Geologically speaking, they’re practically toddlers. Because they’re so young (formed about 34 to 44 million years ago during the Alpine orogeny), they haven’t been worn down by time. That’s why you get these aggressive, needle-like peaks like the Matterhorn. Mont Blanc is the king here, sitting at 4,807 meters.

But here’s what's cool: the Alps aren't just one wall. They are a complex series of massifs. You’ve got the Dolomites in Italy with their weird, pale limestone that turns pink at sunset. Then you’ve got the Bernese Alps in Switzerland with the "Big Three"—the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau. If you’re looking at a map, you’ll notice the Alps form a sort of "C" shape. This shape is why northern Italy is so much warmer than southern Germany; the mountains literally trap the Mediterranean heat and block the cold Arctic winds from moving south.

The Pyrenees: The Wall Between Worlds

I’ve always felt the Pyrenees don’t get enough credit. While the Alps are busy being glamorous, the Pyrenees are just... rugged. They form a natural, brutal border between France and Spain. If you look at a mountain ranges in europe map, the Pyrenees look like a straight line drawn with a heavy hand.

They are older than the Alps. This means the valleys are often narrower and the terrain feels more enclosed. There’s a specific "lost in time" feeling in the Pyrenees. You have micro-states like Andorra tucked away in the high valleys. Because the terrain is so difficult, the people living there—like the Basques—have maintained incredibly distinct cultures and languages that survived for centuries because it was just too much of a pain for invaders to get to them.

The highest point is Aneto, but don't expect the easy infrastructure you find in the French or Swiss Alps. It’s wilder. You’re more likely to run into a bearded vulture or a brown bear here than a five-star resort.

The Carpathians: Europe’s Last Wild Frontier

Move your eyes east on that map. Follow the curve. The Carpathians look like a giant backwards "S" or a horseshoe wrapping around Romania, Slovakia, Poland, and Ukraine.

This is where things get spooky and beautiful.

When you look at the mountain ranges in europe map in the east, the Carpathians represent the largest mountain range in Central Europe. They aren't as high as the Alps—Gerlachovský štít in Slovakia is the highest at 2,655 meters—but they are vast. They hold the largest populations of brown bears, wolves, and lynx in Europe outside of Russia.

Historically, this was the frontier. You have the Transylvanian Alps (the Southern Carpathians) which provided the dramatic, misty backdrop for all those Bram Stoker-inspired myths. But practically? They are vital for timber and minerals. The landscape is a patchwork of primeval forests that haven't changed since the Middle Ages. If you want to see what Europe looked like 500 years ago, this is where you go.

The Scandes: The Spine of the North

Up north, the Scandinavian Mountains (or the Scandes) run the length of the Scandinavian Peninsula. On a map, they look like the jagged backbone of a fish. They aren't particularly tall—Galdhøpiggen in Norway is the highest at 2,469 meters—but they are dramatic because they rise straight out of the sea.

Fjords. That’s the keyword here.

The Scandes were shaped by massive ice sheets during the last ice age. The glaciers carved out deep U-shaped valleys that the sea then filled. This created the Norwegian fjords. The western side of these mountains is incredibly steep and wet, while the eastern side in Sweden slopes gently down toward the Baltic Sea. It's a massive contrast. You can go from a snowy peak to a deep blue sea in a matter of miles.

The Apennines and the Balkans: The Messy Middle

Italy isn't just a boot; it's a boot with a spine. The Apennines run all the way down the center of the country. If you’re looking at a mountain ranges in europe map, you’ll see they almost connect the Alps to Sicily. They make traveling east-to-west in Italy surprisingly annoying. They are mostly limestone and clay, which makes them prone to earthquakes, something central Italy knows all too well.

Then you have the Balkan Mountains.

The term "Balkan" actually comes from a Turkish word meaning "a chain of wooded mountains." This range runs across Bulgaria into Serbia. But confusingly, the "Balkans" as a region includes several ranges: the Dinaric Alps along the Adriatic coast, the Pindus in Greece, and the Rhodopes.

The Dinaric Alps are a karst landscape. Basically, the rock is so soluble that the water has carved out thousands of caves, underground rivers, and sinkholes. It’s a lunar landscape in places. If you’re hiking here, you better bring a lot of water because the surface is bone-dry; all the water is running through the mountains, not over them.

The Urals and the Caucasus: Where Does Europe End?

This is where the mountain ranges in europe map gets controversial. Geography is rarely just about dirt; it's about politics.

The Ural Mountains in Russia are the traditional boundary between Europe and Asia. They are very old and very weathered. They aren't high, but they are incredibly long—about 2,500 kilometers. They are like the Appalachian Mountains of Europe—rich in minerals, metals, and gemstones, which fueled the industrial might of the Soviet Union.

Then there’s the Caucasus.

This range sits between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. If you consider the Caucasus to be the border of Europe, then Mount Elbrus (5,642 meters) is actually the highest mountain in Europe, not Mont Blanc. Most geographers today accept this. The Caucasus are steep, volcanic, and incredibly diverse. There are dozens of languages spoken in these valleys because, much like the Pyrenees, the mountains kept people isolated for millennia.

Why Does This Geography Actually Matter?

It’s easy to look at these ranges as just scenery, but they dictate everything.

- The Rain Shadow Effect: Mountains like the Alps and the Scandes create "rain shadows." This is why one side of a mountain can be a lush rainforest and the other side a dry scrubland. Norway’s west coast is a soggy mess, while parts of Sweden just over the ridge are quite dry.

- The Language Barrier: Why do people in the south of France speak a different dialect than those in northern Spain? The Pyrenees. Why is Swiss German so different from the German spoken in Berlin? The Alps. Mountains are the ultimate "do not disturb" sign for culture.

- The Defense Factor: Historically, if you had a mountain range on your border, you were safe. Switzerland’s neutrality isn't just a political choice; it’s a geographical reality. It’s really hard to invade a country that is basically one big fortress of granite.

How to Actually Use a Mountain Map for Planning

If you’re staring at a mountain ranges in europe map trying to plan a trip, stop looking at the heights and start looking at the passes.

The "height" of a mountain range matters less to a traveler than where the gaps are. In the Alps, the Brenner Pass and the St. Gotthard Pass are the arteries of Europe. Without them, trade would stop. If you're driving, these passes are where you'll spend your time.

👉 See also: Taos New Mexico 87571: Why This High Desert Zip Code Still Trips People Up

Also, pay attention to the seasons. The mountains in Europe have a "short" summer. In the high Tatras or the Alps, snow can block trails well into June. By late September, the weather can turn deadly.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Trip

- Check the "Snow Line": Before booking a hiking trip in May, realize that anything above 2,000 meters in the Alps or Pyrenees will likely still be under snow.

- Look for "Massifs": If you want a variety of terrain in a small area, look for massifs like the Massif Central in France. It’s an ancient volcanic highland that offers a completely different landscape than the jagged Alps.

- Consider the East: The Carpathians (specifically in Romania and Slovakia) offer an Alpine experience for a fraction of the cost. The infrastructure is catching up, but the "wild" factor is much higher.

- Study the Passes: If you’re driving across Europe, map your route through the Great St. Bernard or the Furka Pass for some of the most dramatic (and terrifying) roads on the planet.

- Download Offline Maps: In the deep valleys of the Dinaric Alps or the Urals, your 5G will fail you. Always have a physical map or a downloaded topographical map like Gaia or AllTrails.

The mountain ranges in europe map isn't just a guide to where the land goes up; it’s a blueprint of how the continent breathes, speaks, and moves. Whether you're looking for the limestone caves of the Balkans or the glacial fjords of the North, the terrain is the one thing humans haven't been able to fully conquer. Respect the crinkles on the map. They're bigger than they look.