Manhattan isn't just an island; it’s a grid-iron jigsaw puzzle that somehow makes perfect sense until you hit the West Village and everything goes sideways. If you’re staring at a new york city manhattan map right now, you’re probably trying to figure out how a place so narrow can feel so impossibly vast. It’s barely thirteen miles long. You could walk the whole thing in a day if your shoes are good enough and your willpower is high. But looking at the map is one thing; feeling the rhythm of the streets is another.

Most people see the straight lines of the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan and think, "Easy."

Then they arrive.

The reality of Manhattan’s geography is a mix of rigid 19th-century urban planning and chaotic, pre-colonial cow paths that refused to die. When you look at the map, you see the massive green rectangle of Central Park—843 acres of "don't get lost here after dark"—and the jagged edges of the piers. But the map doesn't tell you that the distance between First Avenue and Second Avenue feels twice as long as the distance between 50th and 51st Street. It’s a trick of the light and the stride.

The Grid: Why the New York City Manhattan Map Looks Like Graph Paper

Back in 1811, a group of guys—the Commissioners—decided Manhattan needed to be organized. They didn't care about "beauty" or "winding vistas." They wanted to sell real estate. They laid out 12 primary north-south avenues and 155 east-west streets.

It’s efficient. It’s brutal. It’s why you can find a Starbucks on 42nd and 8th without a GPS.

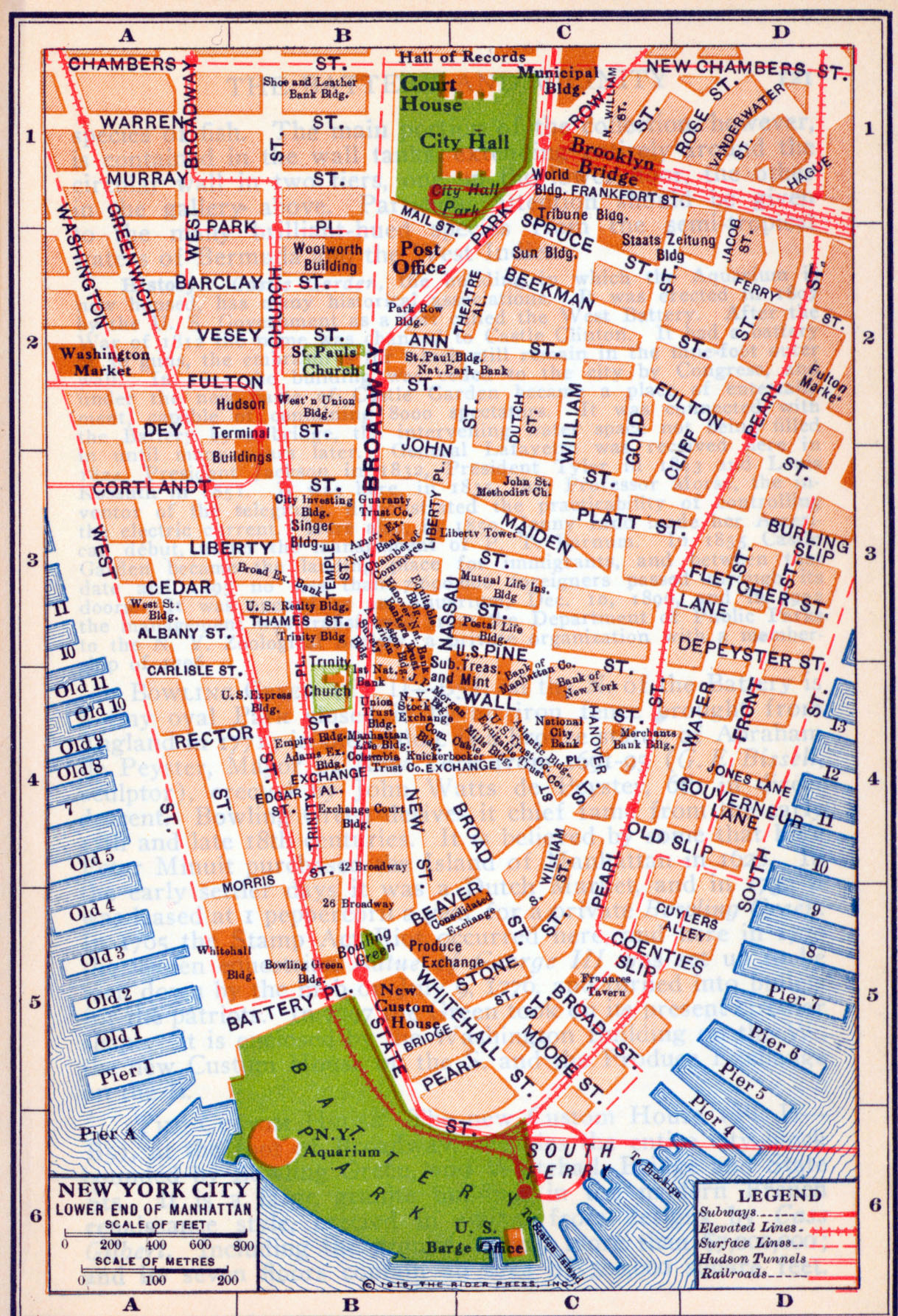

However, the new york city manhattan map has a massive "glitch" at the bottom. Below 14th Street, the grid falls apart. This is where the old Dutch and English settlements were. The streets follow old property lines and topographical quirks. Wall Street? That’s where a literal wall stood. Maiden Lane? That was a path by a stream where women washed clothes. If you’re navigating Lower Manhattan, throw the "number system" out the window. You’re in the land of names like "West 4th" crossing "West 12th," which sounds like a mathematical impossibility but is just a Tuesday in Greenwich Village.

The Avenues and Their Secret Personalities

You can't just talk about the map without talking about the "pulse" of the vertical lines.

- Fifth Avenue is the Great Divider. It splits the island into East and West. If an address is 10 East 23rd, it’s just east of Fifth. If it’s 10 West 23rd, it’s just west. Simple.

- Park Avenue is actually built over a massive train cavern. The Metro-North lines run right under those fancy flower beds.

- Broadway is the rebel. It’s an old Native American trail called Wickquasgeck that cuts diagonally across the entire grid. Because it refuses to follow the 90-degree rules, it creates "bow-tie" intersections wherever it crosses an avenue. That’s how we got Times Square, Herald Square, and Union Square.

Broadly speaking, the map is your safety net, but Broadway is your shortcut. Or your scenic route. Depends on how much time you have to kill.

Understanding the "Vibe" Shifts on the Map

When you look at a new york city manhattan map, the colors usually denote parks or neighborhoods. But the boundaries are often invisible and highly contested by locals. Real estate agents love to invent names like "SoHa" (South of Harlem) or "SpaHa" (Spanish Harlem), but if you say those to a local, expect a cold stare.

Upper Manhattan is hilly. It’s rocky. Places like Washington Heights and Inwood actually have elevation. You’ll find the highest natural point in Manhattan in Bennett Park—265 feet above sea level. It’s a far cry from the flat, reclaimed marshland of Battery Park City.

Midtown is the "canyon." Between 34th and 59th Street, the map is a dense cluster of skyscrapers that block out the sun. This is the Manhattan people see in movies. It's loud. It's crowded. It’s where people who live here usually avoid unless they work in one of those glass boxes.

Water, Water Everywhere

Every new york city manhattan map highlights the Hudson River to the west and the East River... well, to the east. Funny thing? The East River isn't a river. It’s a tidal strait. It connects the Long Island Sound to the Atlantic Ocean. The currents are vicious. If you’re looking at the map and thinking about a casual swim, don't. The Hudson is an estuary, and while it's cleaner than it was in the 1970s, it’s still a working waterway for massive barges and the occasional wayward whale.

The Logistics of Navigating the Map in Real Life

Mapping Manhattan isn't just about streets; it's about the subterranean layers. The subway map is a completely different beast. Sometimes, two stations look close on a street map, but they aren't connected underground.

💡 You might also like: Why the Metra Tracker Live Map is Your Only Real Way to Survive a Chicago Winter

Take the F train. It’s notorious.

You might see a station at 14th Street and 6th Avenue and another at 14th and 8th. They look like neighbors. But if you’re trying to transfer, you’re walking through a long, tile-lined tunnel that feels like a mile.

Expert Tip: Learn the "Street vs. Avenue" walking rule.

Twenty street blocks (going north-south) equal about one mile.

Three avenue blocks (going east-west) equal about one mile.

If you see your destination is five avenues away on the map, you’re in for a hike. If it’s five streets away, it’s a three-minute stroll.

Digital vs. Paper: Which Map Wins?

Honestly? Google Maps is king for the "blue dot" convenience, but a physical new york city manhattan map—the kind they sell in those tourist kiosks for five bucks—is better for understanding the scale of the neighborhoods. Digital maps zoom in so far you lose the context of where Chelsea ends and Hell’s Kitchen begins.

Plus, your phone will die. It’s a law of nature. You’ll be in the middle of the East Village, your battery will hit 1%, and suddenly those winding streets look like a labyrinth designed by a madman.

There’s also the "Citymapper" app, which many locals swear by because it tells you which subway car to get into so you’re closest to the exit. That’s the kind of "pro-level" mapping that saves you four minutes, which in New York time is basically an eternity.

The Landmarks as Compass Points

If you’re lost and the map isn’t helping, look up.

- Empire State Building is roughly 34th Street.

- One World Trade is the South Pole.

- The Chrysler Building is East Side, 42nd Street.

- The Riverside Church tower means you’re way uptown on the West Side.

Using buildings as your north star is how we did it before the iPhone 3G, and it still works.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Manhattan Map

Don't just stare at the lines; use them.

📖 Related: The Great Hall of the People Beijing China: Why This Building Is Actually Massive

- Walk Broadway from 59th down to Union Square. You’ll see the grid system fail and reform in real-time. It’s the best way to understand how the "bow-tie" squares function.

- Download an offline map. The skyscrapers in Midtown create "GPS bounce," where your blue dot thinks you're three blocks away or inside a building. Offline maps help when the signal gets wonky.

- Ignore the "Map North" vs. "True North" confusion. In NYC, "Uptown" is basically Northeast. "Downtown" is Southwest. Don't pull out a literal compass; just follow the street numbers. They go up as you go north.

- Master the L-System. If you're on the East Side and need to get to the West Side, look for the cross-town buses or the L/7/S trains. Manhattan is long, but it’s skinny. Going "across" is often more frustrating than going "up."

- Check the elevation. If you're biking, look at a topographical map. The climb from 125th Street up into Harlem Heights is no joke, even if it looks flat on a standard paper map.

Manhattan is a living organism. The map is just the skeleton. To actually know the city, you have to get lost in the spots where the grid breaks. Go to Christopher Street. Get turned around. Find a tiny bar that shouldn't exist. That’s where the real New York hides, right in the cracks of the 1811 plan.

Locate the "Hunts Point" or "Spuyten Duyvil" on a wider map if you want to see where the island almost touches the mainland. It's a reminder that for all its concrete and steel, Manhattan is still just a rock in the water.