You’re walking across a hardwood floor in wool socks and you slide. It’s fun until you hit the rug and stop dead. That sudden halt, the heat in your tires after a long drive, and the fact that your phone doesn't just slide off the table right now all come down to one thing. We’re talking about the definition for friction.

Most people think of it as a "rubbing" force. That’s partially true, but it’s actually a resistance. It's the force that opposes the relative motion of two surfaces in contact. Basically, it’s nature’s way of saying "not so fast." Without it, the world would be a slippery, chaotic mess where you couldn't even turn a doorknob.

What is the definition for friction, really?

At its most fundamental level, the definition for friction describes the force resisting the sliding or rolling of one solid object over another. It isn't just one "thing" you can point to like a rock or a tree. It’s an interaction. When two surfaces touch, they aren't actually smooth. Even a piece of polished glass looks like a jagged mountain range under a microscope. Friction happens because those microscopic peaks and valleys—called asperities—interlock and get caught on each other.

There’s also a bit of chemistry involved. When atoms on one surface get close enough to atoms on another, they can actually form temporary electrical bonds. You’re essentially "gluing" and "breaking" those surfaces apart thousands of times every second you move them.

It's invisible. It's constant.

The four flavors of friction you deal with daily

Scientists generally break this down into a few specific types. You’ve likely encountered all of them today before you even finished your coffee.

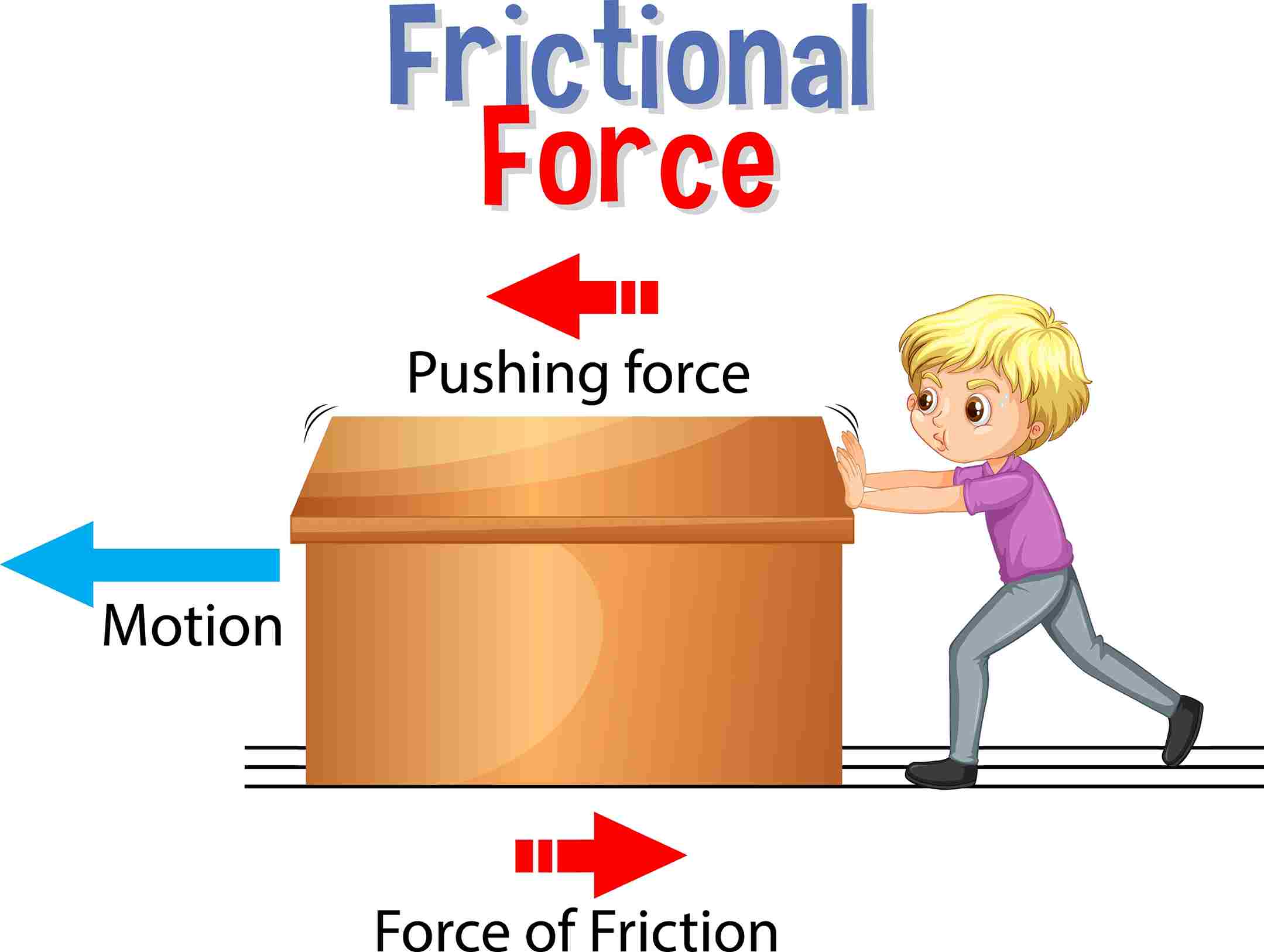

Static friction is the stubborn one. It’s the force that keeps an object at rest. Think about trying to push a heavy couch. You push and push, but nothing happens. That’s static friction pushing back with the exact same amount of force you’re applying. It only breaks once you apply enough "oomph" to overcome those molecular bonds.

Once that couch starts moving, you’re dealing with sliding friction (or kinetic friction). Interestingly, sliding friction is almost always weaker than static friction. This is why it’s harder to get a box moving than it is to keep it moving. Once the "interlocking" of those microscopic jagged edges is broken, they sort of bounce over each other rather than settling in.

Then there is rolling friction. This is why wheels were such a big deal. When a wheel rolls, the point of contact is constantly changing, which minimizes the sliding effect. It’s way more efficient. Finally, we have fluid friction, which is what you feel when you swim or what an airplane deals with in the sky. It’s air or water resistance, technically known as "drag."

Why the "smoothness" of a surface is a lie

We often assume that smoother surfaces have less friction. Usually, that's right. Ice is smoother than sandpaper, so you slip. But physics has a weird sense of humor. If you take two pieces of metal and polish them until they are incredibly, perfectly flat and clean, they will actually stick together better.

In a vacuum, this can lead to "cold welding." Without a layer of air or oxidation between them, the atoms don't know they belong to different objects. They just join up. So, the definition for friction isn't just about roughness; it’s about the total sum of electromagnetic forces between surfaces.

The math behind the resistance

While we’re keeping this conversational, we have to mention the Coefficient of Friction. It’s usually represented by the Greek letter $mu$ ($\mu$).

📖 Related: Why Your Choice of SWAT Team Gas Mask Actually Matters in a Crisis

The formula looks like this:

$$F_f = \mu F_n$$

In this equation, $F_f$ is the force of friction, $\mu$ is the coefficient (how grippy the materials are), and $F_n$ is the normal force (how hard the surfaces are being pressed together).

If you want more friction, you either change the material (get grippier shoes) or you increase the weight (put a heavy person on the sled). It’s why race cars use spoilers to push the car down onto the track. They are artificially increasing the "normal force" to get more grip without adding the actual weight that would slow the car down.

Real-world friction: The good, the bad, and the hot

Friction is a double-edged sword. Honestly, we spend half our time trying to create it and the other half trying to kill it.

- The Good: Brakes. When you hit the brake pedal, pads clamp down on a rotor. The friction converts that kinetic energy into heat, stopping your car. No friction? You’re going through the intersection.

- The Bad: Engine wear. Inside your car's engine, pistons are firing thousands of times a minute. Friction here is the enemy. It creates heat that can melt metal and causes parts to wear down. This is why we use oil—a lubricant—to create a thin film that keeps the metal parts from actually touching.

- The Hot: If you’ve ever rubbed your hands together to stay warm, you’re using friction to generate thermal energy. On a larger scale, space capsules entering the atmosphere rely on fluid friction with the air to slow down, but it generates so much heat they need massive heat shields to keep from vaporizing.

Misconceptions that drive physicists crazy

One big myth is that friction depends on the surface area. You’d think a wider tire would have more friction than a skinny one, right?

Actually, for most solid objects, the surface area doesn't matter much. If you flip a brick on its side, the friction remains largely the same. Why? Because while the area increased, the pressure (force per unit area) decreased. They cancel each other out. Wide tires on race cars are mostly about heat management and preventing the rubber from shredding, not just "more friction" in the way we usually think.

Another one is that friction always opposes motion. Not quite. Friction is what allows you to walk. When you step, your foot pushes backward against the ground. Friction pushes forward on your foot. In this case, friction is actually the force causing your forward motion.

How to use this knowledge

Understanding the definition for friction helps in everyday life more than you'd think. If you’re moving furniture, use sliders to turn sliding friction into something closer to rolling friction. If your car is stuck in snow, don't just spin the tires—that creates heat, melts the snow into ice, and lowers your coefficient of friction. Instead, put something rough down, like floor mats or kitty litter, to give those microscopic "jagged edges" something to grab onto.

Actionable takeaways for managing friction

- Check your tires: The tread isn't just for show; it's designed to channel water away so your rubber stays in contact with the road. If you "hydroplane," you've replaced solid friction with fluid friction, and you lose control.

- Lubricate strategically: Don't just use WD-40 for everything. It’s a solvent, not a long-term lubricant. Use silicone or lithium grease for hinges and gears where you want to permanently reduce wear.

- Heat management: If you're using power tools like a drill, remember that friction creates heat. If the bit gets too hot, it loses its "temper" and becomes soft. Periodically pulling the bit out to let it cool is just smart physics.

- Footwear choice: If you're hiking on loose scree, you want a "high mu" sole with deep lugs. On a bowling alley, you want low friction so you can glide. Match the gear to the resistance you need.

Friction is the silent tax we pay on every movement we make. It’s why machines eventually break and why we can't have perpetual motion machines. But it’s also the only reason we can stay upright, drive safely, and hold a cup of coffee. It is the literal glue of the physical world.