You ever try to walk on a sheet of black ice? It’s terrifying. One second you're upright, the next your legs are doing a cartoonish scramble and you’re staring at the sky. That terrifying lack of control happens because you’ve lost your grip. In scientific terms, you’ve lost the invisible force that makes modern life possible. So, what is friction in physics anyway? Most people think it’s just things rubbing together. It’s actually way weirder than that. It’s a messy, microscopic battle happening between surfaces every single nanosecond.

Friction is essentially a resistance. It’s the force that opposes the relative motion of two surfaces. If you push a book across a wooden table, it eventually stops. Why? Because the table and the book are "talking" to each other at a molecular level, and they aren't exactly getting along.

The Microscopic Ruggedness You Can’t See

If you looked at a "smooth" piece of metal under a powerful electron microscope, it wouldn't look smooth at all. It would look like the Himalayan mountain range. There are peaks (called asperities) and deep valleys. When two surfaces touch, these peaks slam into each other. They get tangled. In some cases, they actually "cold weld" together for a split second.

This is why friction exists. It’s not just a "concept"; it’s physical interference. When you try to slide that book, you have to exert enough force to either break those microscopic peaks or lift the book over them. This is also why heavier objects are harder to move. The more weight you add, the harder those microscopic peaks are smashed together, increasing the contact area and making the "interlocking" much stronger.

The Two Faces of Friction: Static vs. Kinetic

There’s a weird thing about physics: it’s harder to get something moving than it is to keep it moving.

🔗 Read more: The mac os safari update Nobody Talks About: Why Your Browser Feels Different Now

Static friction is the stubborn one. It’s the force that keeps an object stuck in place. Imagine trying to push a heavy couch. You push, and push, and nothing happens. You’re fighting static friction. The molecules are settled. They’re cozy. They’ve had time to deform and bond slightly.

Then, suddenly, the couch "pops" loose. Now you’re dealing with kinetic friction (or sliding friction). Kinetic friction is almost always weaker than static friction. Once the object is moving, those microscopic peaks are basically skimming over each other. They don't have time to settle into the valleys or form deep bonds. This is why if your car tires start spinning on mud, you’re in trouble—you’ve lost the high-grip static friction and transitioned into the much lower kinetic friction zone.

The Math That Drives Engineers Crazy

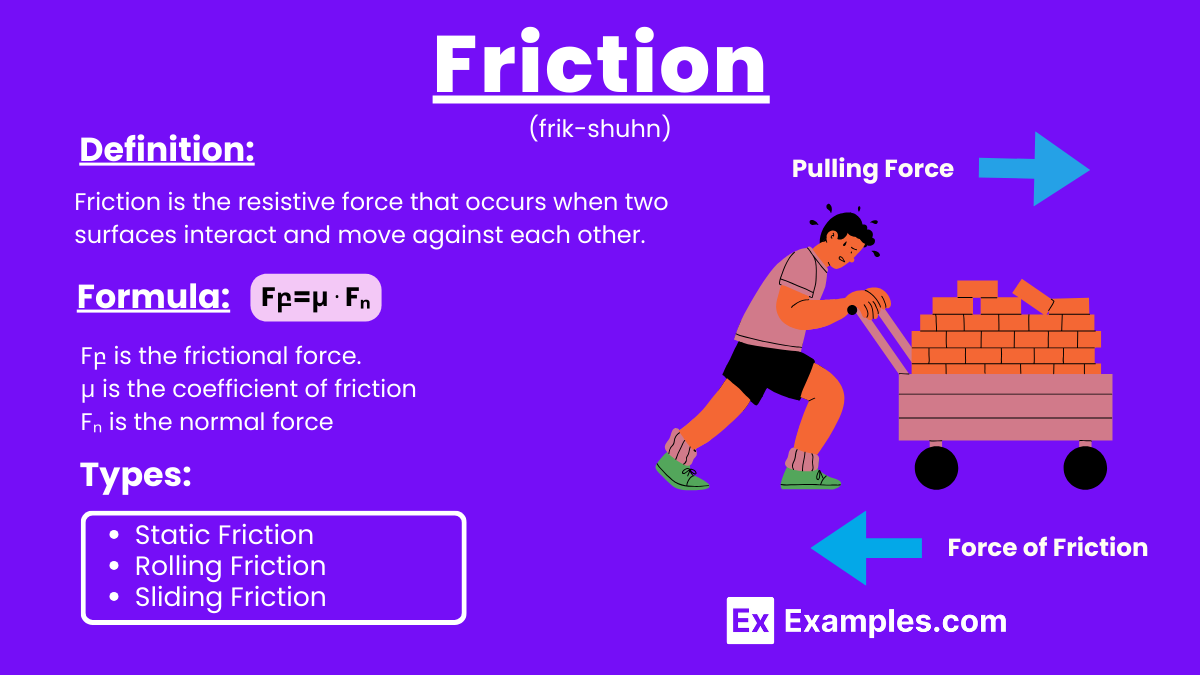

Engineers spend their lives obsessed with the Coefficient of Friction. It’s represented by the Greek letter $\mu$ (mu). Basically, it’s a ratio that tells you how "grippy" two materials are when they meet.

$$f = \mu N$$

In this equation, $f$ is the friction force, $\mu$ is the coefficient, and $N$ is the "Normal Force" (how hard the surfaces are being pressed together). There isn't just one "friction number" for rubber. There’s a number for rubber-on-concrete, rubber-on-ice, and rubber-on-wet-grass. They are all wildly different. Formula 1 engineers lose sleep over this. They need the highest $\mu$ possible to take corners at 200 mph, which is why they use "soft" tires that practically melt onto the track to increase that molecular bond.

Fluids and Air: Friction in Disguise

Friction isn't just for solids. If you’ve ever tried to run through waist-deep water, you’ve felt drag. This is fluid friction. It depends on the viscosity of the fluid and the shape of the object. Air is a fluid too, technically. When a skydiver jumps out of a plane, air resistance (friction with air molecules) is the only thing preventing them from accelerating indefinitely. Eventually, that friction equals the force of gravity, and they hit "terminal velocity." They stop getting faster.

Why We Actually Need Friction to Survive

We complain about friction when it wears out our favorite sneakers or makes our car engines overheat, but without it, the world would be a nightmare.

- Walking: Your shoes "push" against the ground. Without friction, your feet would just slide backward like you’re on a treadmill made of grease.

- Driving: Brakes work by converting kinetic energy into heat through friction. No friction? No stopping.

- Knots: Ever wonder why a shoelace stays tied? Friction holds the loops together.

- Atmospheric Protection: Meteors burn up in the atmosphere because of the intense friction with air molecules. Without it, we’d be pelted by space rocks daily.

The Downside: Heat and Wear

While it’s useful, friction is also the enemy of efficiency. It’s estimated that a massive chunk of the world’s energy consumption goes toward overcoming friction in machinery. It creates heat. This is why your phone gets hot when you play a high-end game or why a drill bit feels like lava after you make a hole in a 2x4.

To fight this, we use lubricants. Oil, grease, even air bearings. Lubricants work by filling in those microscopic "valleys" we talked about earlier. Instead of jagged peaks hitting jagged peaks, you have a layer of slippery molecules that let the surfaces glide. It’s the difference between rubbing two pieces of sandpaper together and rubbing two pieces of silk.

Surprising Truths: Does Surface Area Matter?

Here is a fun fact that breaks most people’s brains: in many basic physics models, the amount of surface area does not change the amount of friction.

Wait, what?

It seems counterintuitive. You’d think a wider tire would have more grip than a skinny one. But according to Amontons's First Law of Friction, the force of friction is independent of the area of contact. If you have a brick, it should take the same amount of force to slide it whether it's lying flat or standing on its end.

Now, in the real world (especially with "squishy" things like rubber tires), this law gets a bit messy because of molecular adhesion and deformation. But for hard solids, surface area is surprisingly irrelevant. It’s all about the pressure and the materials.

Real-World Case Study: The Columbia Space Shuttle

Friction isn't just a classroom topic; it’s a matter of life and death. When a spacecraft re-enters the Earth's atmosphere, it's traveling at roughly 17,500 miles per hour. The friction between the ship and the air molecules is so intense it creates plasma, with temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The 2003 Columbia disaster was caused by a breach in the thermal protection system—the "shield" designed to handle that friction. A small hole allowed that heat to get inside the wing, leading to structural failure. It’s a sobering reminder that friction is a force of immense power.

How to Use This Knowledge

Understanding friction isn't just for physicists. It’s practical.

- Check your tires: When the tread wears down, you aren't just losing "grooves" for water; you're changing the way the rubber interacts with the road. If the rubber gets "heat-cycled" and hardens, your coefficient of friction drops, and your stopping distance rockets up.

- Home Maintenance: If a door hinge squeaks, don't just spray oil everywhere. Realize you're trying to separate two metal surfaces that are literally grinding each other down at a microscopic level.

- Sports Performance: Whether it’s chalking your hands for a deadlift (increasing friction) or waxing a surfboard (reducing drag), you are manually manipulating the laws of physics to your advantage.

Friction is the silent, invisible glue of our universe. It’s a "wasteful" force that generates heat and wears things out, but it’s also the only reason you can sit in a chair without sliding onto the floor. It’s messy, it’s complicated, and it’s happening right now between your fingers and whatever device you’re holding.

Actionable Next Steps

To see friction in action, try these three things today:

- The Phone Book Challenge: If you have two old phone books or magazines, interleave the pages one by one. Try to pull them apart. You won't be able to. The cumulative friction of hundreds of pages is stronger than a human's pull.

- Temperature Check: Rub your hands together vigorously for 30 seconds. Feel that heat? You’re literally feeling the kinetic energy of your movement being converted into thermal energy via molecular collisions.

- Lubrication Audit: Look at the "high-friction" zones in your life—car engines, bike chains, or even a sliding glass door. Check if the lubricants are dry. Replacing a $10 bottle of oil can save a $1,000 piece of machinery from the destructive power of "peaks hitting peaks."