Honestly, if you look at a map of the Philippine Islands, your first thought is probably "That's a lot of green." It is. But here's the thing: it’s actually more than most people realize. For decades, we all learned in school that there were 7,107 islands. Then, around 2016, the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) used high-resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar and realized they’d missed a few. The count jumped to 7,641.

Most of these are just tiny specks of rock or sandbars that disappear when the tide gets high.

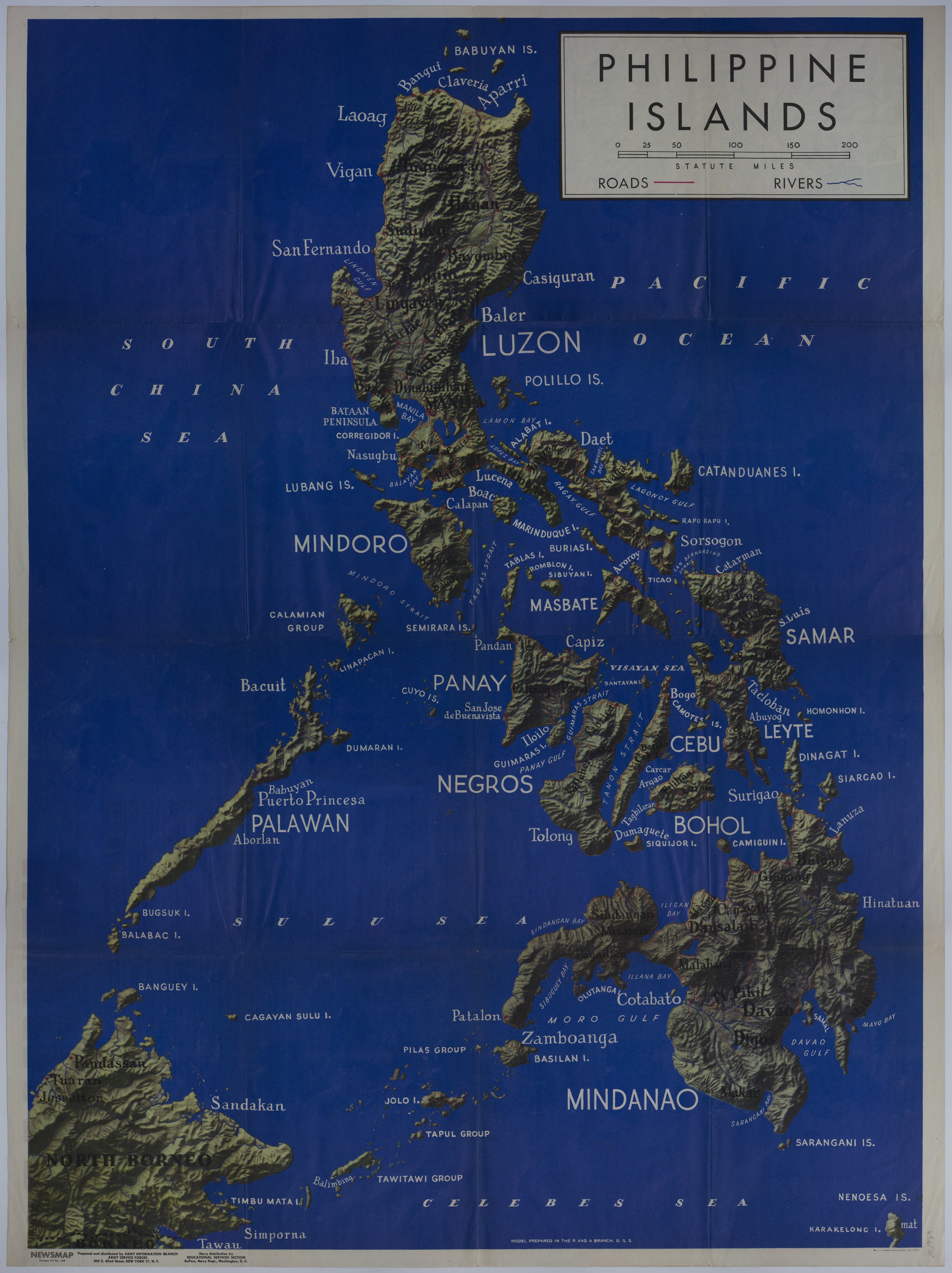

Looking at the map isn't just about geography; it’s about understanding how a country stays connected when it’s literally split into thousands of pieces by the Pacific Ocean, the South China Sea (or West Philippine Sea, depending on who you ask), and the Celebes Sea. It’s a logistical nightmare. It’s also beautiful. When you zoom in on a map of the Philippine Islands, you aren't just looking at landmasses. You’re looking at a massive, complex jigsaw puzzle of 82 provinces and three main groups: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

Luzon is the big one up north. It’s where the power is. You’ve got Manila, the sprawling, chaotic capital, and the rugged Cordillera Mountains where the rice terraces look like they were carved by giants. Then there’s the Visayas in the middle—the "island-hopping" capital—and Mindanao down south, which is huge, fertile, and often misunderstood.

Why a Map of the Philippine Islands is Never Actually Finished

Geography is alive. In the Philippines, this isn't a metaphor. Because the archipelago sits right on the Pacific Ring of Fire, the map changes. Volcanic eruptions, like the massive 1991 Pinatubo event, literally rearranged the topography of Central Luzon. Siltation and rising sea levels mean that what was a beach ten years ago might be underwater now.

Take the Spratly Islands or the Kalayaan Island Group. If you look at an official government-issued map of the Philippine Islands, you’ll see these small features included within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). But if you look at a map printed elsewhere, those lines might look very different. Geography here is political. It’s about sovereignty and fishing rights. It’s about the "nine-dash line" versus the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

It’s messy.

Then you have the bathymetry—the map of what’s under the water. The Philippine Trench is one of the deepest spots on Earth. If you dropped Mount Everest into it, you’d still have a couple of kilometers of water above the peak. That’s a wild thought. Most travelers just see the white sand of Boracay or the limestone cliffs of El Nido, but the map extends deep into the dark.

The Three Pillars: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao

You can’t just talk about the map as one big blob. You have to break it down.

Luzon is the economic engine. It’s the largest and most populous island. If you’re looking at the map, notice the Cagayan Valley up north. It’s cradled by the Sierra Madre mountain range to the east and the Cordillera Central to the west. The Sierra Madre is basically the country’s spine; it takes the brunt of the typhoons coming in from the Pacific, protecting the plains of Central Luzon. Without those mountains, the "Rice Granary of the Philippines" would be a wasteland.

The Visayas is different. It’s a scattered collection of medium-sized islands. Cebu, Bohol, Leyte, Samar, Panay, and Negros. This is where the Spanish first landed. When Magellan sailed in 1521, he wasn't looking for a "map of the Philippine Islands" because the concept didn't exist yet. He was looking for spices and stumbled into a central hub of trade that had been connecting China, Southeast Asia, and India for centuries.

Mindanao is the "Land of Promise." It’s the second-largest island and is geologically distinct from the rest. It has the highest peak in the country, Mount Apo. While Luzon and Visayas get hammered by typhoons every year, Mindanao is mostly outside the "typhoon belt." This makes its map look incredibly green because the agriculture is so consistent. Pineapples, bananas, durian—this is where your supermarket fruit probably comes from.

Navigating the "Seas" Within the Map

One thing people get wrong when looking at a Philippine map is ignoring the water between the islands. The Sibuyan Sea, the Visayan Sea, the Camotes Sea—these aren't just empty spaces. They are vital highways.

Before the Americans brought planes and the Spanish brought better roads, the Filipinos were a maritime culture. The balangay boats were how people moved. If you lived in Cebu, it was easier to get to northern Mindanao by boat than it was to trek across the mountains of your own island.

The "Ro-Ro" system (Roll-on/Roll-off) is the modern version of this. It’s a network of highways that includes ferry hops. You can literally drive a bus from Manila all the way to Davao City in Mindanao by "driving" onto boats. On a map, this looks like a dotted line connecting the islands, but in reality, it’s a grueling, multi-day journey of salty air and humid terminal waiting rooms.

The Misconception of Size

Maps are lying to you. Usually, it's the Mercator projection making Greenland look as big as Africa. In the Philippines, the scale is deceptive. The country is about the size of Italy or Arizona. But because it’s fragmented, it feels ten times larger.

Traveling 100 miles on a map of the Philippine Islands is not the same as traveling 100 miles in Kansas.

In the Philippines, 100 miles might involve a three-hour drive on a winding mountain road, a two-hour wait at a pier, a four-hour ferry ride, and another hour on a tricycle. The map doesn't show the "time-distance," which is the only metric that actually matters here.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Persia on the Map: Why the Name Changed and Where It Is Today

Real Talk: The Accuracy of Google Maps vs. Reality

If you’re using a digital map to navigate the rural Philippines, be careful. Google Maps is great in BGC or Makati. It’s "okay" in Cebu City. But once you get into the provinces of Samar or the highlands of Bukidnon, things get weird.

I’ve seen "roads" on a map that were actually just dried-up creek beds. Or "shortcuts" that lead to a dead-end cliff. Local knowledge always beats the GPS. If the map says it takes two hours to get from Puerto Princesa to El Nido, give yourself six. The map doesn't know about the landslide, the ongoing road widening, or the herd of water buffalo (carabao) blocking the lane.

The Hidden Maps: Tectonic and Linguistic

There are maps you can’t see on a standard political print.

First, the tectonic map. The Philippines is a "tectonic melange." It’s caught between the Eurasian Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate. This is why the country is so mountainous and why the map is dotted with active volcanoes like Mayon (the one with the perfect cone) and Taal (the volcano inside a lake inside a volcano).

Second, the linguistic map. This is fascinating. Even though there’s a national language (Filipino/Tagalog), the map is divided into over 170 living languages.

- North: Ilocano and Pangasinense.

- Central Luzon: Tagalog and Kapampangan.

- The South: Maranao, Maguindanao, and Tausug.

- The middle: The "Bisaya" group (Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray).

A map of the Philippine Islands is essentially a map of different nations forced together by colonial history. When you cross a body of water, the language often changes completely. A Tagalog speaker in the middle of a market in Bacolod might feel more like a foreigner than they would in Los Angeles.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Best YMCA Camp Campbell Photos: What Parents and Campers Actually Need to See

Modern Mapping and the Future

We’re getting better at mapping the islands. Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards) was a massive leap forward, using LiDAR technology to create high-resolution maps that predict flooding. In a country that gets 20 typhoons a year, a good map isn't a luxury; it’s a survival tool.

Climate change is redrawing the map. Some of the smaller islands in the Tawi-Tawi group or the low-lying areas of Bulacan are literally sinking—or the water is rising. The "official" 7,641 number might go down again in our lifetime.

Actionable Insights for Using a Philippine Map

If you are planning a trip or studying the region, don't just look at a flat image.

- Check the Terrain Layer: If you're traveling, always switch to "Terrain" or "Satellite" view. A "short" distance on a flat map might be a 5,000-foot mountain pass in reality.

- Respect the EEZ: If you’re looking at maps for maritime or political reasons, understand the difference between the "Archipelagic Baselines" and the "Exclusive Economic Zone." They serve different legal purposes.

- Use NAMRIA for Accuracy: For the most authoritative, government-sanctioned data, go to the source. The National Mapping and Resource Information Authority has the most detailed topographical maps available.

- Local Navigation Apps: While Google is king, apps like Waze are surprisingly popular in Manila and Cebu because they crowdsource data on traffic and floods—two things a static map will never show you.

- Look for the "Geoportals": The Philippine government has a centralized geoportal where you can overlay different data sets like fault lines, protected forest areas, and mining zones. It’s a goldmine for researchers.

The Philippines is a country of "too much." Too many islands to visit in a lifetime, too many languages to learn, and too much geography to fit on a single piece of paper. Whether you're a trekker looking for the next peak or a developer looking for land, just remember that the map is just a suggestion. The real Philippines is what happens when you put the map away and actually start moving.