Most people look at a diagram of a nuclear reactor and see a terrifying mess of pipes and warning symbols. It looks like a Rube Goldberg machine designed by someone who hates sleep. Honestly, though? It’s basically just a high-tech way to boil water. That’s the big secret. We’ve split the atom, harnessed the fundamental forces of the universe, and we use all that god-like power just to make tea-kettle steam to spin a big fan.

If you’ve ever stared at those blue-tinted schematics and felt your brain itch, you aren't alone. The complexity isn't in the concept; it's in the layers upon layers of "what if this breaks?" engineering.

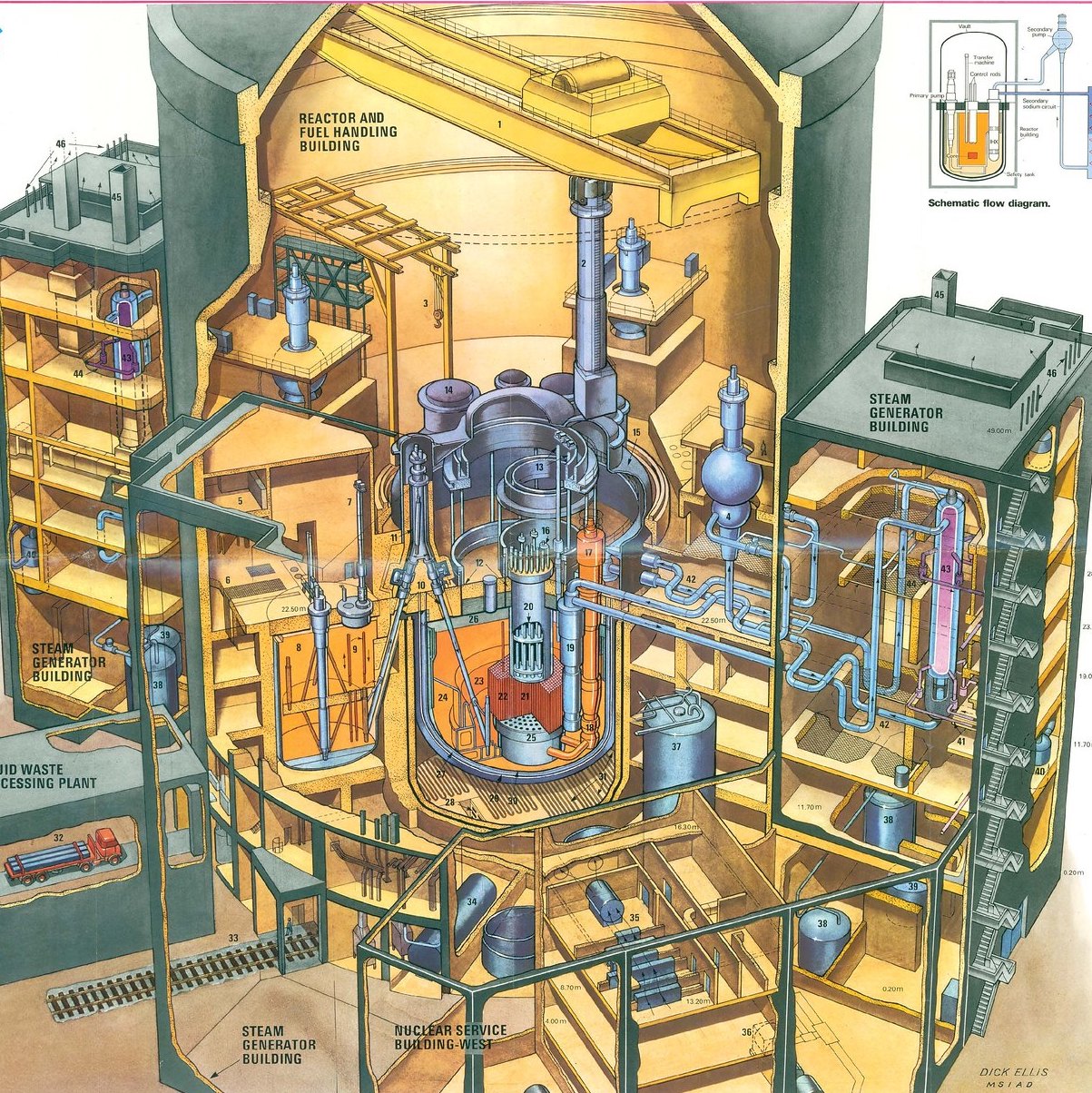

The Core is Where the Magic (and Heat) Happens

At the dead center of any diagram of a nuclear reactor, you’ll find the core. This is the engine room. Imagine a giant, thick steel pressure vessel—we’re talking walls that are often six to ten inches of solid steel. Inside this beast sit the fuel assemblies. These aren't just lumps of green glowing rock like in The Simpsons. They are long, slender tubes filled with small ceramic pellets of Uranium-235.

Neutrons fly around in there like pinballs. When a neutron hits a uranium atom, the atom splits. This is fission. It releases more neutrons and a staggering amount of heat.

But you can't just let those neutrons go wild. If they move too fast, they actually miss the other atoms. It's counterintuitive, but you have to slow them down to keep the fire going. This is where the "moderator" comes in. In most American reactors, like the ones run by Exelon or NextEra Energy, that moderator is just plain old water. It slows the neutrons down so they can keep hitting targets.

✨ Don't miss: iPad Pro Burn In: What Most People Get Wrong

Then you have the control rods. These are the brakes. They are made of materials like boron or cadmium that "soak up" neutrons like a sponge. If things get too hot, you drop the rods in. No neutrons, no fission, no heat. Simple.

Why There Are So Many Loops

If you look closely at a diagram of a nuclear reactor, you’ll notice the water isn't just one big pool. It’s usually divided into "loops." This is the most important part of the safety design.

In a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR)—the most common type globally—the water touching the fuel never actually leaves the containment building. It’s kept under such insane pressure that it can't boil, even though it's screaming hot, sometimes over 600 degrees Fahrenheit. This "primary loop" carries the heat away from the core and into a heat exchanger.

Think of it like a radiator in a car. The radioactive water stays in its own pipes, passing its heat to a secondary loop of clean water. That secondary water turns into steam, rushes out to the turbine hall, and spins the generator.

By the time you see steam coming out of those iconic hourglass-shaped cooling towers, that water has never been anywhere near the radiation. It's just clean water vapor. The "scary" stuff is locked behind three or four different walls of steel and concrete.

The Cooling Tower Misconception

Everyone thinks the cooling tower is the reactor. It’s not. In fact, some reactors don’t even have them if they are near a large enough body of water like the ocean or a massive river.

The cooling tower is just the final stage of the "third loop." After the steam spins the turbine, you have to turn it back into water so you can pump it back to the heat exchanger. You do this by running it past pipes filled with cold water from a river or lake. That's why reactors are always built next to water. The cooling tower is just a giant chimney for excess heat.

What Most Diagrams Leave Out

Most diagrams make it look like a quiet, static environment. It’s not. It is a place of incredible mechanical violence. The pumps required to move thousands of gallons of water per second are the size of small houses. The vibrations are intense.

Also, the "Blue Glow." You’ve probably seen photos of reactor pools glowing with a ghostly blue light. That’s Cherenkov radiation. It happens when particles travel faster than the speed of light in that specific medium (water). It’s the visual equivalent of a sonic boom. Most simplified diagrams of a nuclear reactor won't show you that, but it’s a real, physical phenomenon that engineers use to monitor the core's activity.

Different Flavors of Reactors

Not every diagram of a nuclear reactor looks the same.

- BWR (Boiling Water Reactor): These are simpler but slightly "messier." They let the water boil right in the core. The steam that spins the turbine is actually a bit radioactive, which means the turbine building has to be shielded. GE-Hitachi is the big name here.

- CANDU (Canada Deuterium Uranium): These use "heavy water." It's water where the hydrogen atoms have an extra neutron. This allows them to use natural uranium without expensive enrichment.

- RBMK: This is the Chernobyl design. It used graphite as a moderator instead of water. Modern safety standards have basically moved away from this design because it was inherently unstable at low power.

The Concrete Fortress

The final layer of any reactor diagram is the containment building. This is that giant concrete dome. It’s not just a shed. It’s reinforced with a web of steel rebar and designed to withstand the impact of a literal jetliner.

Inside that dome, the air pressure is actually kept lower than the outside air. Why? Because if there's a tiny leak, air blows in, not out. It's these tiny, "invisible" engineering choices that make modern nuclear power one of the safest forms of energy generation per terawatt-hour, despite the high-profile accidents of the past.

Looking Ahead: SMRs

The future of the diagram of a nuclear reactor is actually getting smaller. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are the new hotness. Companies like NuScale are designing reactors that can be built in a factory and shipped on a truck.

In these diagrams, the "loops" are often integrated into a single vessel. They use "passive safety," meaning if the power goes out, the water circulates naturally by gravity and convection without needing pumps. No pumps means no chance of a pump failing. It’s a "walk-away" safe design.

How to Read the Schematics Like a Pro

When you're looking at a diagram next time, follow the heat.

🔗 Read more: Nude Pictures on Instagram: What’s Actually Allowed and the Risks You’re Taking

- Start at the fuel rods (heat source).

- Follow the primary coolant (the carrier).

- Look for the steam generator (the hand-off).

- Follow the steam to the turbine (the work).

- Watch the steam hit the condenser (the reset).

If you can trace those five steps, you understand more about nuclear physics than 90% of the population. It’s a dance of thermodynamics that provides roughly 20% of the electricity in the United States without emitting a single gram of carbon dioxide during operation.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're trying to learn more or perhaps even looking into a career in nuclear engineering, don't just stop at the 2D drawings.

- Check out the NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) website. They have a "Student Corner" with technical maps of every active reactor site in the US.

- Use Virtual Tours. Places like the Byron Generating Station sometimes offer 360-degree views of the turbine deck—it gives you a sense of scale that a flat diagram never can.

- Study the "Steam Tables." If you really want to understand the efficiency of these machines, look into how water changes properties at 150 atmospheres of pressure. That’s where the real engineering "magic" happens.

The next time you see a diagram of a nuclear reactor, remember you’re looking at a giant, sophisticated, incredibly safe steam engine. We've just swapped the coal for the power of the stars.