You type ls or dir. You hit Enter. A split second later, a list of files appears. It feels like magic, or at least like a very simple reaction, but the journey from your fingertip to the silicon gates of your processor is a chaotic, high-speed relay race. Most people think the command line is just a "text version" of clicking an icon. It isn't. When you ask how does CPU process from command line inputs, you’re looking at a fundamental shift in how hardware interprets human intent.

The CPU doesn't know what a "command" is. It doesn't know what "Linux" or "Windows" is. To the processor, everything is just a series of electrical pulses representing 1s and 0s stored in specific memory addresses. The command line is just the interface that translates your human language into the brutal, mathematical logic of the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA).

The Shell is the Middleman

Before the CPU even gets a whiff of your command, your shell—be it Bash, Zsh, or PowerShell—has to do the heavy lifting. Think of the shell as a translator sitting in a glass booth. When you type grep "error" log.txt, the shell doesn't just pass that string to the processor. The CPU would have no idea what to do with a string of ASCII characters.

First, the shell parses the input. It breaks the string into tokens. It identifies grep as the executable, "error" as the pattern, and log.txt as the target. It looks through your PATH environment variable to find where the actual binary file for grep lives on your disk. Once found, the shell calls the operating system kernel (using a system call like fork() and execve() in Unix-like systems) to create a new process.

This is where the CPU finally enters the chat. The kernel tells the CPU: "Hey, I need you to stop what you're doing, or at least carve out some time, to run these specific instructions located at this memory address."

The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle

Once the kernel has loaded the program's machine code from your SSD into the RAM, the CPU starts its relentless rhythm. This is the Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle. It happens billions of times per second (GHz).

🔗 Read more: Why Every Picture of Space Junk You See Is Actually Terrifying

- Fetch: The Control Unit (CU) of the CPU looks at the Program Counter (PC). This register holds the memory address of the next instruction. The CPU fetches that instruction from the RAM. But RAM is slow compared to a CPU, so it usually pulls it from the L1 or L2 cache first.

- Decode: The instruction is just a hex code, like

0x48 0x89 f8. The decoder turns this into micro-operations. It figures out that this specific bit pattern means "Move the value from register A to register B." - Execute: The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) does the actual math. If your command line instruction involves comparing two strings, the ALU performs the subtractions or bitwise shifts required to see if they match.

It’s easy to forget that at this level, there is no "text." There are only voltages. A "1" is a high voltage; a "0" is a low voltage. The CPU is essentially a massive city of microscopic switches (transistors) being flipped on and off by the beat of a crystal oscillator clock.

Interrupts: Why Your Computer Doesn't Freeze

If the CPU just sat there waiting for you to finish typing your command, your computer would be useless. This is handled by interrupts. When you press a key on your keyboard while using the command line, the keyboard controller sends a hardware interrupt signal to the CPU.

The CPU literally drops what it's doing. It saves its current state (the "context") and jumps to an Interrupt Service Routine (ISR). It notes the key you pressed, puts it in a buffer, and then goes back to its previous task. This happens so fast you never notice the "pause" in your background music or your web browser's rendering.

When you finally hit Enter, the shell triggers a software interrupt. It signals to the kernel that a full command is ready for processing. This transition from "User Mode" (where you type) to "Kernel Mode" (where the CPU does the sensitive work) is a high-security handoff that prevents your command line typos from accidentally wiping out the CPU’s ability to manage the power supply or the cooling fans.

Registers and the Speed of Light

Within the CPU, the data isn't just floating around. It lives in registers. These are the fastest storage locations in the entire computer. When you run a command line tool like awk or sed to process data, the CPU is constantly shuffling bits between the RAM and these registers.

A modern CPU like an AMD Ryzen 9 or an Intel Core i9 has several types of registers:

📖 Related: Why the Apple Vision Pro 2 Matters More Than You Think

- General Purpose Registers: Used for temporary data storage during calculations.

- Floating Point Registers: For complex decimal math.

- Status Registers: These hold "flags" (e.g., did the last math operation result in zero? Did it overflow?).

The physical distance between the registers and the ALU is measured in micrometers. This is because, at multi-gigahertz speeds, even the speed of light becomes a bottleneck. If the data had to travel all the way from the RAM for every single instruction, the command line would feel as sluggish as a 1990s dial-up connection.

Why Command Line is "Faster" Than GUI

You've probably heard tech geeks claim the command line is faster. They aren't just talking about their typing speed. From a CPU perspective, a Graphical User Interface (GUI) is a nightmare of overhead.

To display a window, the CPU (and GPU) must calculate millions of pixel colors, handle transparency layers, track mouse coordinates, and manage complex window "events." When you run a command via the terminal, the CPU bypasses almost all of that. It doesn't have to render a "Delete File" animation. It just calls the file system API, updates the pointers on the disk, and returns a success code.

For the processor, command line operations are "lean." The ratio of actual work (the task you want done) to overhead (the stuff needed to show you the task) is much higher.

Real-World Example: The cat Command

Let's look at a simple command: cat hello.txt.

- User input: You type it. The shell gets the string.

- System Call: The shell asks the kernel to open

hello.txt. - I/O Request: The CPU sends a command to the disk controller. "Give me the data at these blocks."

- Wait/Context Switch: Since the disk is slow, the CPU doesn't just wait. It switches to another task (like updating your clock) while the disk controller does its thing.

- Data Transfer: The disk controller moves the file data into a buffer in RAM.

- Output: The kernel tells the CPU to move that data from the RAM buffer to the terminal's standard output. The CPU executes instructions to copy these bytes to the video memory buffer so you can see the word "Hello" on your screen.

Misconceptions About CPU Usage

One common myth is that the command line doesn't "stress" the CPU. That’s false. If you run a command like find / -name "*.tmp", you are asking the CPU to perform millions of comparisons and manage heavy I/O traffic.

📖 Related: Can I Trade In a Cracked iPhone? Here’s the Brutal Truth About What Your Phone is Actually Worth

Another misconception is that the CPU "understands" the command line better than a GUI. It doesn't. Both eventually become the same machine code. The difference lies in the layers of abstraction. The command line has fewer layers. It's like talking to a chef directly versus sending a letter to the restaurant's corporate office to ask for a sandwich.

Summary of the Journey

The process looks like this:

- Human Input → String of text in the shell.

- Parsing → Shell turns text into executable paths and arguments.

- Kernel Intervention → The OS sets up the environment and memory.

- The Loop → CPU fetches, decodes, and executes machine instructions.

- Hardware Interaction → ALU does the math, registers hold the data, and interrupts handle the timing.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Your CPU

If you want to see this in action on your own machine, you don't need a lab. You can use the command line itself to watch the CPU's "thought process."

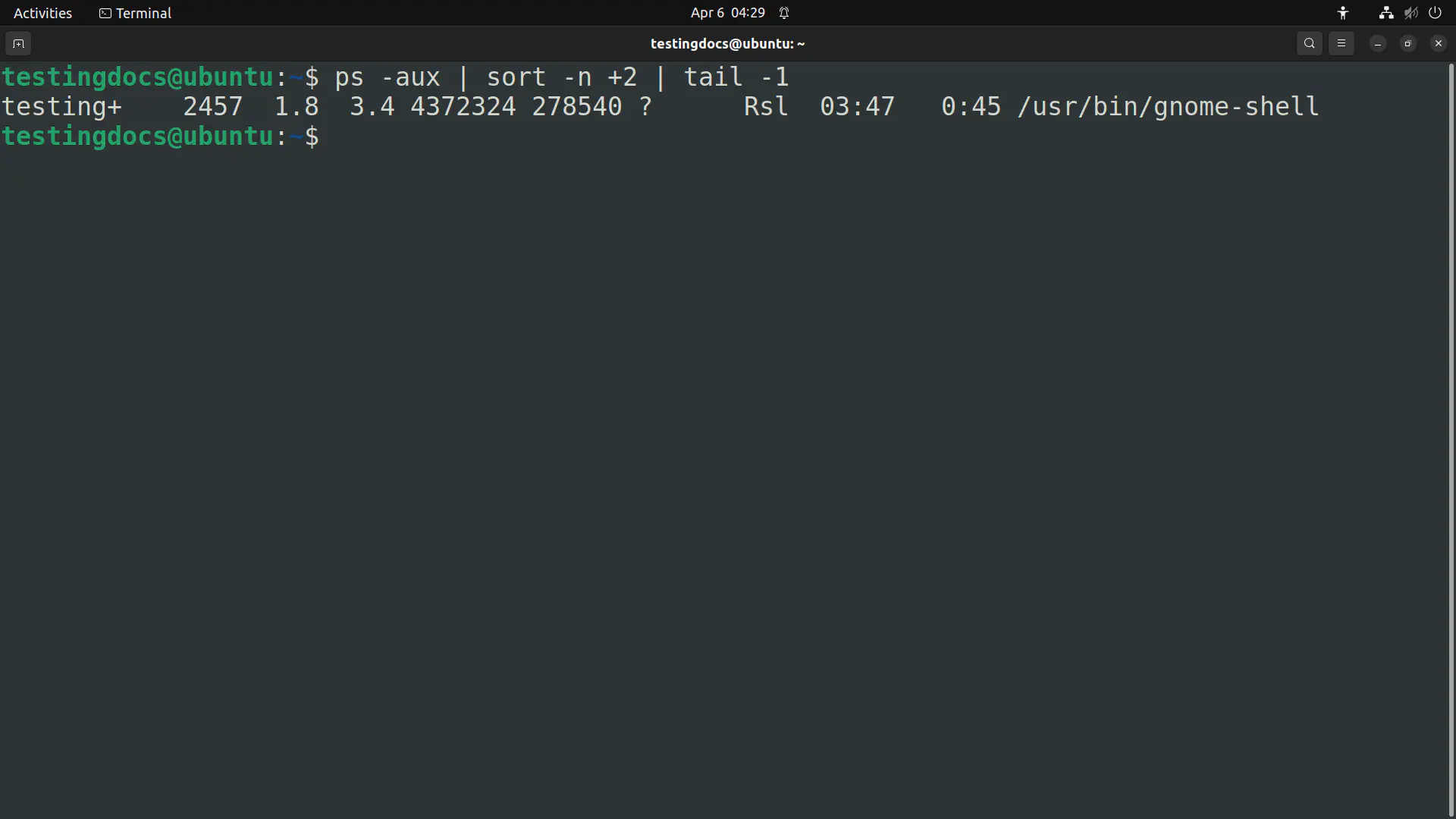

- Watch the System Calls: On Linux or macOS, run

strace ls(ordtruss ls). You will see every single system call the CPU handles just to list your files. It’s a staggering amount of work for such a simple task. - Monitor Instruction Cycles: Use

toporhtopto see how different command line tools tax your "User" vs "System" (kernel) CPU time. - Check the Architecture: Type

lscpu(Linux) orsysctl -a | grep machdep.cpu(macOS). This shows you the specific registers and cache sizes your CPU uses to process these commands. - Try a "Dry Run": If you are writing a script, use

set -xin Bash. This shows you exactly how the shell expands your commands before they ever hit the processor.

Understanding the link between a text command and a silicon chip changes how you view computing. It isn't just a screen showing you icons; it's a massive, invisible machinery of logic gates operating at the limits of physics. Every time you hit Enter, you're conducting a billion-piece orchestra.