You’re standing in your backyard, looking up at a tiny, fast-moving pinprick of light. It’s the International Space Station (ISS). You might think it’s halfway to the moon. Or maybe it’s just past the clouds? Honestly, neither is even close. If you could drive your car straight up, you’d be there in about four hours. That’s a shorter trip than driving from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

When people ask how far to the space station, they usually expect a number in the thousands. The reality is much more "down to earth." The ISS orbits at an average altitude of approximately 250 miles (400 kilometers). To put that in perspective, that’s roughly the distance between Washington D.C. and New York City. It’s right there. You could practically touch it if the atmosphere weren't so thin and the station wasn't screaming across the sky at five miles per second.

The "falling" trick that keeps the station up

Distance is only half the story. If you just went 250 miles up and stopped, you’d fall like a rock. Space isn't a place where gravity just stops working. In fact, gravity at the station's altitude is still about 90% as strong as it is on your living room floor. The only reason the astronauts don't plummet back to Earth is because they are moving sideways incredibly fast.

They are essentially in a state of perpetual freefall. Imagine throwing a baseball. It curves down to the ground. Now imagine throwing it so hard that the curve of its fall matches the curve of the Earth. That’s an orbit. The ISS has to maintain a speed of about 17,500 mph to stay at that 250-mile distance. If it slows down, it gets closer to Earth. If it speeds up, it pushes further away.

Why does the distance keep changing?

You can’t just give one static number for how far to the space station because the station isn't in a perfect circle. It’s an ellipse. Sometimes it’s a bit lower, maybe 230 miles. Other times, the flight controllers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center or Roscosmos give it a "reboost."

See, even at 250 miles up, there’s a tiny bit of atmosphere. It’s very thin, but it creates drag. This drag acts like a microscopic brake, slowly tugging the station toward the planet. Without periodic engine burns from docked spacecraft like the SpaceX Dragon or the Russian Progress, the ISS would eventually spiral down and burn up in the atmosphere. This happened to Skylab in 1979. We learned our lesson.

Seeing it with your own eyes

Because it’s so close, the ISS is actually the third brightest object in the sky after the Sun and the Moon. You don't need a telescope. You just need to know when to look. NASA has a tool called "Spot the Station" that sends you texts when it's passing over.

- It looks like a steady white light.

- It doesn't twinkle like a star.

- It doesn't have blinking lights like an airplane.

- It moves way faster than any jet you’ve ever seen.

The distance between you and the station also depends on where it is in its pass. When it’s directly overhead (at the zenith), it’s at its closest—that roughly 250-mile mark. But when it's first appearing on the horizon, it might be over 1,000 miles away from your specific eyeballs.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) vs. Deep Space

To understand the distance, you have to understand the neighborhood. The ISS lives in Low Earth Orbit. This is the "inner city" of space.

Compare this to the Moon. The Moon is about 238,000 miles away. If the Earth were a basketball and the Moon were a tennis ball, the Moon would be about 24 feet away. In that same scale, the International Space Station would be about a quarter of an inch (around 6 millimeters) from the surface of the basketball.

🔗 Read more: Finding a MacBook Pro Case 13 inch That Actually Protects Your Gear Without Looking Cheap

It's a tiny gap. This proximity is vital for survival. If something goes wrong—like a cooling leak or a medical emergency—astronauts can get home in a few hours. When we eventually send humans to Mars, the distance will be millions of miles. There, "how far" becomes a question of months, not miles.

The logistics of getting there

Getting 250 miles away isn't the hard part. It’s the speed. To reach the station, a rocket like the Falcon 9 has to accelerate a crew capsule to that 17,500 mph mark while precisely timing the "intercept." It's like trying to jump onto a speeding merry-go-round that’s also a few hundred miles in the air.

- Launch Window: You have to launch exactly when the Earth’s rotation brings the launch pad under the station’s orbital path.

- The Catch-up: Usually, the spacecraft starts at a lower altitude where it can move faster relative to the Earth to catch up to the ISS.

- The Docking: This is a slow, methodical dance. Even though both are moving at thousands of miles per hour, their relative speed to each other is only a few inches per second.

What most people get wrong about the vacuum

There’s a common myth that the space station is "outside" of Earth’s influence. It’s not. It’s actually still inside the thermosphere, a layer of the atmosphere where temperatures can reach 4,500°F (though it wouldn't feel hot because the molecules are so far apart).

The station is far enough to be "in space" by the Karman Line definition (which is 62 miles up), but it's close enough to be our backyard laboratory. This proximity allows for high-speed communication and frequent resupply missions. We are currently in an era where private citizens are paying for trips to this 250-mile-high destination through companies like Axiom Space.

Actionable steps for tracking the station

If you want to experience the distance yourself, don't just read about it.

First, get a tracking app. Use "ISS Detector" or NASA's official site. Look for "Max Height" in the sightings. Anything over 40 degrees means it's coming close to your location.

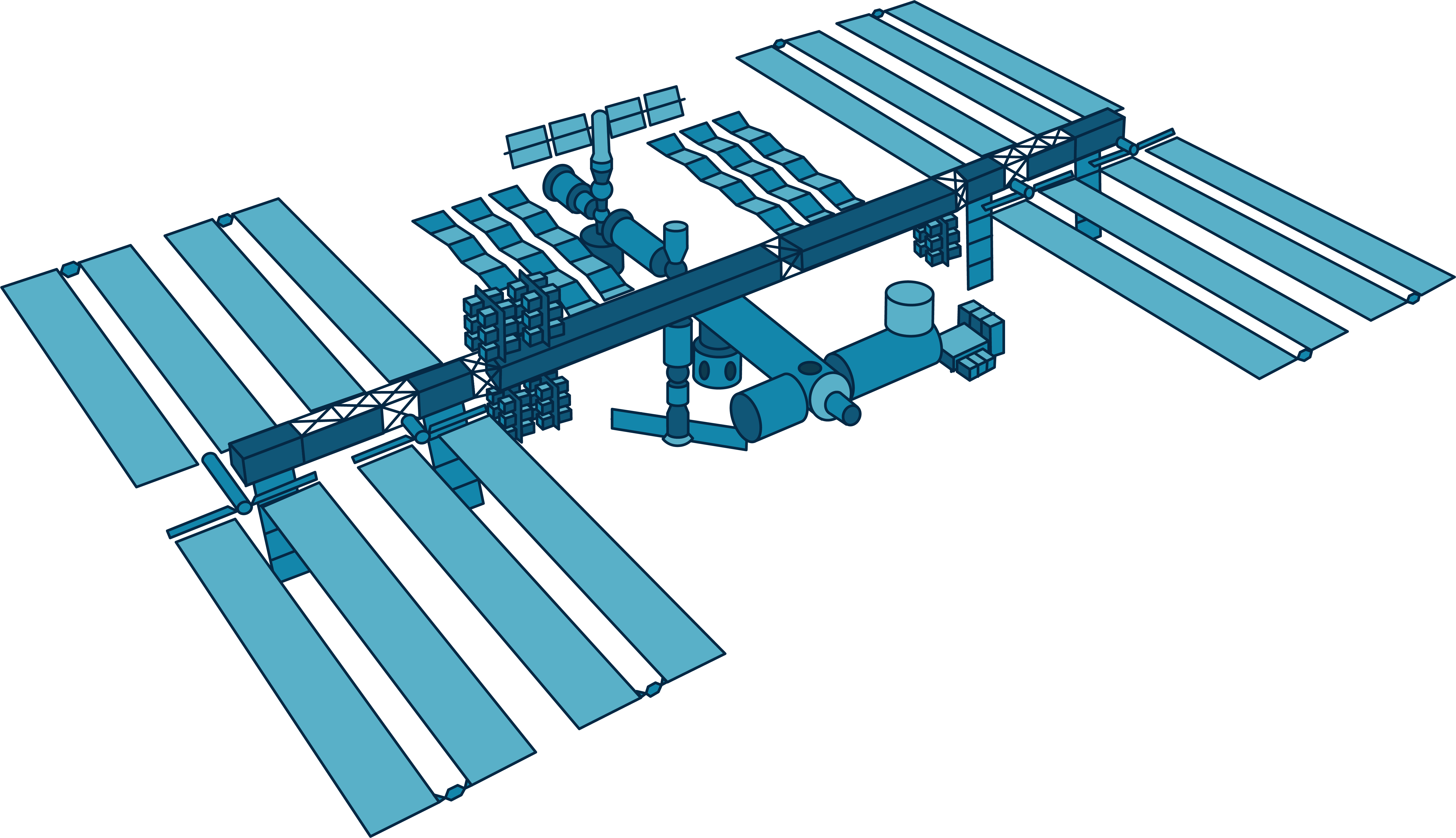

Second, grab some binoculars. While the ISS moves fast, a decent pair of 10x50 binoculars can actually reveal the structural shape of the station—the long solar arrays and the central truss—if you can steady your hands enough.

Third, check the "reboost" schedule. If you notice the station's altitude suddenly "jumps" on a tracking chart, you’re seeing the result of a spacecraft's engines pushing the station back up into its proper orbit. It's a literal reminder that gravity is always trying to pull our greatest technological achievement back down to the dirt.

Stay curious about the sky. The distance isn't as vast as you think, which somehow makes the fact that people are living up there even more incredible.