Ever looked at your phone and wondered why your area code is what it is? Or why some numbers start with a 0 or a 1 while others don't? Most people figure we’ve got an infinite supply of digits. We don't. It’s a finite, strictly regulated grid. When you ask how many phone number combinations are there, you aren’t just asking a math question. You’re asking about the North American Numbering Plan (NANP), a massive logic puzzle that keeps billions of devices from screaming at each other simultaneously.

The short answer? About 8 billion. But that’s a "spherical cow in a vacuum" kind of answer. The real-world reality is way more cluttered by government red tape and technical legacy rules from the days of rotary phones.

The basic math of the 10-digit system

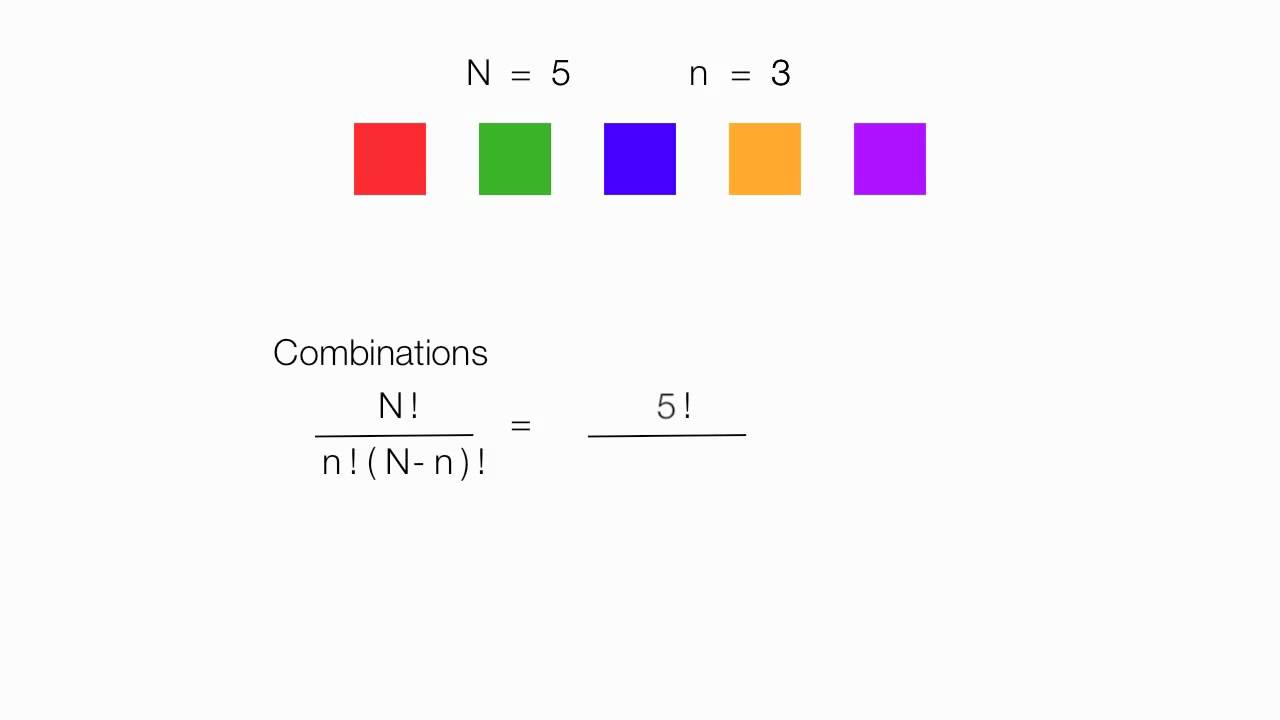

Let's do the raw numbers first. In the US, Canada, and several Caribbean nations, we use a 10-digit format. If you just took ten slots and filled them with any number from 0 to 9, you’d have $10^{10}$ combinations. That’s 10 billion. Simple, right?

Not even close.

📖 Related: WD Black SN770 1TB Explained: Why This Mid-Range SSD Still Dominates in 2026

We have rules. These rules are set by the NANP. They dictate that your phone number is split into three parts: the Area Code (Numbering Plan Area or NPA), the Central Office Code (the prefix), and the Line Number. Each part has its own set of "illegal" digits. For instance, an area code can't start with a 0 or a 1. Why? Because back in the day, the switching equipment used 0 to reach an operator and 1 to signal a long-distance call. If your area code started with a 1, the system would have a meltdown trying to figure out if you were dialing a location or just trying to call your aunt in another state.

Why you can't just pick any digits

To understand how many phone number combinations are there, we have to filter out the restricted zones.

For the Area Code (the first three digits), the first digit (N) can be anything from 2 to 9. That gives us 8 options. The second and third digits (X) can be anything from 0 to 9. So, $8 \times 10 \times 10 = 800$ possible area codes.

But wait. There are "Easily Recognizable Codes" or ERCs. These are numbers where the second and third digits are the same, like 800, 888, or 911. Some of these are reserved for toll-free services. Others, like 911 or 411, are N11 codes reserved for public services. You can't have a personal area code of 911. It’s literally impossible.

Then we look at the prefix—the middle three digits. Same rule applies: the first digit can't be 0 or 1. Also, the second and third digits cannot both be 1 if the area code is also an ERC. This prevents technical glitches in the routing software.

So, when you crunch the actual allowed permutations, you get:

- 800 possible Area Codes (minus about 76 reserved or N11 codes).

- 792 possible Central Office codes per area code.

- 10,000 possible line numbers (0000 through 9999).

When you multiply these out, the theoretical maximum is roughly 6.3 billion usable numbers for the entire NANP region. That’s a lot, but it isn't 10 billion.

The ghost of the rotary phone

It’s kinda funny how old tech still haunts us. Ever notice how big cities have area codes with low middle numbers? New York is 212. Chicago is 312. Los Angeles is 213.

This wasn’t a coincidence. On a rotary phone, dialing a "1" takes a fraction of a second. Dialing a "9" takes forever as the dial spins back. The engineers at AT&T and Bell Labs gave the biggest cities the "fastest" area codes to save wear and tear on the equipment and save time for the highest volume of callers.

This legacy created a weird distribution of how many phone number combinations are there in specific regions. Even though we don’t use rotary dials anymore, those assignments created the "overlay" system we use today. When a city runs out of those 7.9 million numbers in a specific area code, the FCC doesn’t just make up new digits. They slap a new area code right on top of the old one. That’s why your neighbor might have a 646 number while you have a 212.

The "Running Out" Panic

Are we going to run out? People have been freaking out about "exhaustion" for decades. In the 90s, the explosion of fax machines and pagers (remember those?) nearly broke the system. Suddenly, every household needed three numbers instead of one.

Today, it’s the Internet of Things (IoT). Your "smart" fridge doesn't just need electricity; it needs an identity. Your car has a SIM card. Your iPad has a data plan with a "shadow" phone number attached to it even if you never use it to make a call.

The North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) releases reports every year predicting when we will hit the wall. Currently, they estimate the current 10-digit system will last well past the year 2050.

💡 You might also like: Why Won't My Apple CarPlay Connect? The Real Reasons Your Car is Ghosting Your iPhone

What happens when the 6 billion run out?

Honestly, we’ll probably just add a digit. Moving to an 11-digit or 12-digit system would increase the combinations exponentially. If we added just one digit to the area code, we’d jump from 6 billion to 60 billion.

But the hardware transition would be a nightmare. Every database, every "Contact Us" form on a website, every emergency dispatch system, and every piece of legacy telecom switching gear would need a software overhaul. We saw a tiny version of this with the Y2K bug. Changing the fundamental structure of a phone number is the telecom equivalent of changing the side of the road everyone drives on.

Real-world constraints and "Dirty" numbers

You’d think with billions of combinations, you could easily get a fresh number. Nope.

Most "new" numbers are actually "recycled." When someone cancels their service, that number sits in a "cooling off" period for a few months before being handed to a new subscriber. If you’ve ever gotten a phone number and immediately started getting texts for a guy named "Dave" who owes money to a collection agency, you’ve experienced the scarcity of how many phone number combinations are there.

Technically, there are billions of numbers, but the "clean" ones—the ones that haven't been associated with a human in the last decade—are incredibly rare.

Why some numbers are worth thousands

Because the total count is limited, "vanity" numbers have become a massive secondary market. Numbers with repeating digits (like 222-2222) or numbers that spell out businesses (1-800-FLOWERS) are treated like digital real estate. There are brokers who do nothing but trade these specific combinations.

- Scarcity drives value: In the 212 area code, a "nice" number can sell for $5,000 or more.

- The "800" factor: True 800 numbers are gone. That’s why we have 888, 877, 866, 855, 844, and 833. Each time one prefix fills up, the regulators unlock a new one.

- Local identity: In places like London (which uses a different system), the length of the number can actually tell you how old the line is.

Beyond North America: The Global Scale

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) sets the global standard under a recommendation called E.164. This says a phone number can have a maximum of 15 digits.

💡 You might also like: Why the Download on App Store Logo is Still a UX Masterclass

If you take the entire planet into account, the number of combinations is staggering. With a 15-digit limit, you’re looking at $10^{15}$, or one quadrillion possible numbers. That is more than enough for every human to have a hundred devices each.

China and India use different internal structures because of their massive populations. They often use 10-digit mobile numbers starting with specific digits (like 9, 8, or 7 in India) to differentiate between providers and circles.

Actionable insights for the digital age

Knowing the math is one thing, but dealing with the reality of number exhaustion is another. If you're looking to secure your digital footprint, keep these facts in mind:

- Protect your number: Since there is a finite supply of "clean" numbers, treat yours like a Social Security number. Once you lose a number, getting it back is nearly impossible because it goes back into the giant "recycling" bin.

- VoIP is a loophole: Services like Google Voice or Burner apps allow you to tap into these combinations without a physical SIM card. This is the best way to test if a specific area code has available "inventory."

- Check the "First Use" history: If you are buying a business number, use a reverse lookup tool to see how many "owners" it has had. High turnover usually means the number is on a dozen telemarketing lists.

- Watch the NPA-NXX: If you’re a developer, never hard-code phone number lengths or formats into your databases. The "10-digit rule" is a regional convention, not a universal law. Systems should always be built to handle the E.164 15-digit maximum to stay future-proof.

The 8 billion combinations we have today seem like plenty, but in a world where your toaster, your watch, and your car all want to "talk," those digits disappear faster than you'd think. We aren't just managing numbers; we're managing the finite addresses of our digital lives.