You’ve probably held two fridge magnets together and felt that weird, invisible push. It’s a literal wall of force. You try to shove them together, but they slide off to the side like they’re greased. We call these north and south magnets, but honestly, the names are kind of arbitrary. They could have been called "up and down" or "plus and minus," but we stuck with geography because of how they interact with the giant rock we live on.

Magnets aren't magic.

📖 Related: The Day the Earth Smiled: Why This 2013 Space Photo Still Gives Us Chills

They are the result of electron spin alignment. In most things—like your wooden coffee table or a plastic spoon—the electrons are spinning in every which way. They cancel each other out. But in a permanent magnet, like a neodymium slab or a piece of magnetite, those spins align. They create a unified field. It’s like a crowd of people all screaming in different directions versus a stadium chanting the same word in unison. That collective "shout" is the magnetic field.

Why Do We Even Call Them North and South?

It’s about the Earth. Period. If you hang a bar magnet from a string, it’s going to twist. It doesn't do this for fun; it's aligning with the Earth's magnetic field. The end that points toward the Arctic is what we labeled the "North-seeking pole." Over time, we just shortened it to the North pole.

Here is where it gets kind of trippy: physically speaking, the Earth’s geographic North Pole is actually a magnetic south pole. Since opposites attract, the north pole of your compass is being pulled toward a magnetic south. Scientists like William Gilbert figured this out way back in 1600. His book De Magnete was basically the first real deep dive into this, debunking the idea that magnets were attracted to a giant "magnetic mountain" in the north or that garlic could demagnetize a compass. People actually believed the garlic thing.

The poles are inseparable. You can’t have a north without a south. If you take a hacksaw and cut a bar magnet right down the middle, you don’t end up with one north piece and one south piece. You get two smaller magnets, each with its own north and south. This is known as the "no magnetic monopoles" rule in Gausss’s law for magnetism. While some theoretical physicists are hunting for a single-pole particle in the Large Hadron Collider, as of 2026, we haven't found one that actually stays stable.

The Field Lines: Mapping the Invisible

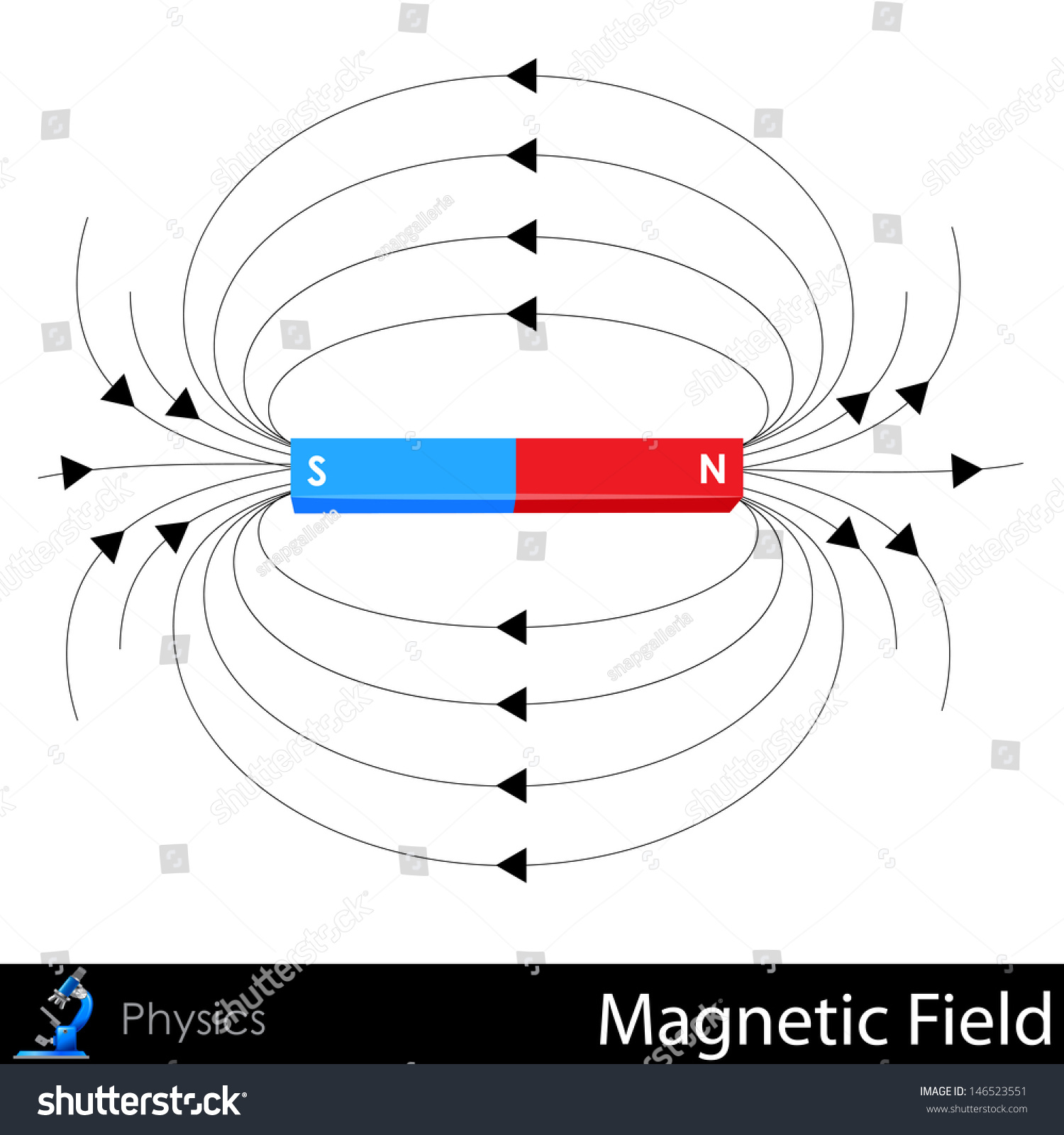

Imagine iron filings sprinkled on a piece of paper with a magnet underneath. They form these beautiful, loopy arcs. These are magnetic field lines.

By convention, we say the field "flows" out of the North and into the South. It’s a loop. Inside the magnet itself, the field is actually moving from South to North to complete the circuit. It’s a continuous, never-ending stream of flux. The closer these lines are together, the stronger the force. This is why the tips of the magnet—the poles—are so much more powerful than the middle. If you try to pick up a paperclip with the exact center of a bar magnet, it’ll usually just fall off. The "action" is at the ends.

Practical Uses You Use Every Single Day

We aren't just talking about fridge poetry here. North and south magnets run the modern world.

Your smartphone has several of them. The speakers use a permanent magnet and an electromagnet to vibrate a cone and make sound. The haptic engine—that little vibration you feel when you type—is a magnet being tossed back and forth by an electric field.

Then there’s the big stuff:

- MRI Machines: These use massive superconducting magnets to align the protons in your body. It’s literally "Magnetic Resonance Imaging."

- Maglev Trains: These use the "like poles repel" principle to levitate a multi-ton train. No friction means they can hit 370 mph without breaking a sweat.

- Hard Drives: Traditional HDDs store data by flipping the polarity of tiny magnetic grains on a spinning platter. A north-up might be a "1" and a south-up might be a "0."

The Weirdness of Electromagnetism

You can make a magnet with nothing but a battery, some copper wire, and a nail. This is an electromagnet. When electricity flows through a wire, it creates a magnetic field. Wrap that wire into a coil (a solenoid), and you concentrate that field.

The cool part? You can flip the north and south poles just by reversing the direction of the current. If you swap the wires on the battery terminals, the magnet’s "identity" flips instantly. This is the foundation of the electric motor. By constantly flipping the poles of an internal magnet, you can make it "chase" another magnet in a circle, creating rotation. This turns electrical energy into mechanical work. It’s how your Tesla moves, how your blender makes a smoothie, and how your ceiling fan keeps you cool.

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

People think magnets pull on all metals. They don't. Aluminum, copper, gold, silver—magnets won't touch 'em under normal circumstances. Only "ferromagnetic" materials like iron, nickel, and cobalt really get the party started.

Another one: "Magnets can heal your blood." You see those "magnetic therapy" bracelets everywhere. The logic is that since blood has iron (hemoglobin), the magnet will improve circulation. This is basically a scam. The iron in your blood is not ferromagnetic; it’s actually slightly diamagnetic (it’s weakly repelled by magnets). Plus, the magnets in those bracelets aren't nearly strong enough to penetrate your skin and affect blood flow in a meaningful way. If they were, you wouldn’t be able to walk past a refrigerator without getting stuck to it.

The Future of Magnetic Polarity

We are getting better at manipulating these fields. Researchers at MIT and CERN are working on high-temperature superconductors that could make fusion power a reality. To hold a sun-hot plasma in place, you need incredibly precise, incredibly strong magnetic fields. We are talking about magnets that could lift an aircraft carrier.

Even in computing, we are moving toward "spintronics." Instead of moving electrons around (which creates heat), we might just flip their magnetic spin to process information. It’s faster, cooler, and more efficient.

Actionable Steps for Handling Strong Magnets

If you’re working with neodymium magnets (the silver ones), you need to be careful. They aren't toys.

- Keep them away from electronics. While modern SSDs are mostly fine, strong magnets can still wreck sensors, credit card strips, and old-school mechanical watches.

- Slide, don't pull. If two strong magnets are stuck together, trying to pull them apart is a losing game. Slide them sideways. It takes way less force to overcome the friction than the direct magnetic pull.

- Watch your fingers. Neodymium magnets can snap together with enough force to shatter bone or blood blisters. Treat them like a loaded power tool.

- Storage matters. Store magnets in "attracting" pairs with a "keeper" (a piece of iron) across the poles if possible. This keeps the magnetic field contained and prevents it from demagnetizing other nearby objects over years of storage.

The relationship between north and south poles is the literal glue of the universe’s electromagnetic force. It's predictable, it's symmetrical, and it's why your compass works in the middle of the woods. Understanding that the "pull" is just a search for balance between these two poles makes the technology around us feel a lot less like magic and a lot more like clever engineering.