You’ve probably heard it a thousand times: the Sun is just an average star. It’s the ultimate "C-student" of the cosmos, sitting right in the middle of the pack. But honestly? That’s kinda a lie.

When you look at the Sun compared to other stars in our local neighborhood, it’s actually a bit of a beast. Most stars in the Milky Way are red dwarfs—tiny, dim, and cranky little things that make our Sun look like a glowing titan. If you randomly picked a star out of a hat, there’s a 75% chance it would be an M-dwarf, a star so small and cool that it doesn't even glow white-hot; it glows a dull, ruddy orange.

So, our Sun isn't "average." It’s in the top 10% of stars by mass.

We live next to a G-type main-sequence star. Astronomers call it a "yellow dwarf," which is a pretty weird name considering it’s actually white. The only reason it looks yellow to us is because our atmosphere scatters the blue light away. If you were floating in the ISS, you'd see a blindingly white ball of plasma.

The Scale of the Neighborhood

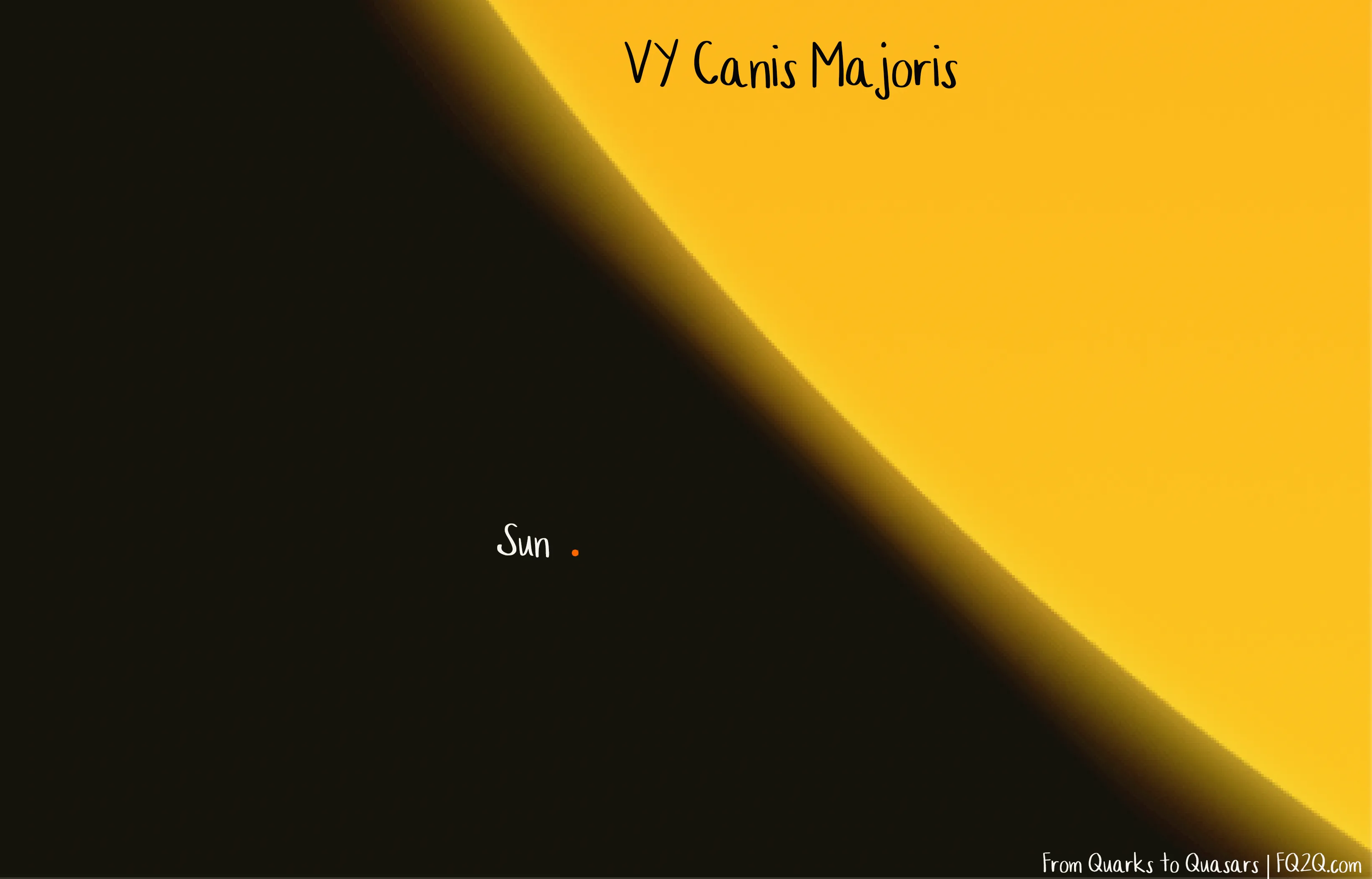

Let’s talk size. It’s hard to wrap your head around how big space stuff is. You could fit 1.3 million Earths inside the Sun. That sounds huge. And it is! But compared to a monster like UY Scuti or Betelgeuse, our Sun is basically a grain of sand.

Betelgeuse, that bright red shoulder in the constellation Orion, is a red supergiant. If you swapped our Sun for Betelgeuse, the surface of that star would extend past the orbit of Mars, maybe even Jupiter. It’s terrifying. It’s a bloated, dying star that’s destined to go supernova any day now (though "any day" in space terms means sometime in the next 100,000 years).

But here’s the kicker: those giant stars are rare. Super rare.

For every one Betelgeuse, there are millions of stars like our Sun. And for every star like our Sun, there are dozens of red dwarfs. Proxima Centauri, our closest neighbor, is one of those red dwarfs. It’s so dim you can’t even see it with the naked eye, even though it’s "right next door" at 4.2 light-years away. If Proxima Centauri were the size of a grapefruit, the Sun would be a large beach ball, and Betelgeuse would be the size of several city blocks.

Temperature and the Color Game

The Sun compared to other stars also sits in a "Goldilocks" zone of temperature. It burns at about 5,500 degrees Celsius on the surface.

Stars come in a specific order of temperature that astronomers remember with the mnemonic "O Be A Fine Girl/Guy, Kiss Me."

- O-type stars are the hottest. They are blue, massive, and live fast and die young. We’re talking 30,000 degrees plus.

- M-type stars (the red dwarfs) are the coolest, sitting around 2,500 to 3,500 degrees.

Our Sun is a G-type.

Why does this matter? Because of the "Habitable Zone." Since our Sun is relatively stable and moderately hot, its habitable zone—the area where liquid water can exist—is at a comfortable distance. Around a tiny M-dwarf, the habitable zone is so close to the star that any planets there would likely be "tidally locked." One side would always face the star and roast, while the other side would be a permanent frozen wasteland. Not exactly a vacation spot.

The Longevity Factor

Big stars are gas guzzlers.

A star that is ten times more massive than the Sun doesn't live ten times longer. It lives a fraction of the time. It has so much gravity crushing its core that it burns through its hydrogen fuel at a terrifying rate. An O-type star might only live for a few million years. That’s nothing. Life on Earth took billions of years just to move past single-celled sludge.

Our Sun has a total lifespan of about 10 billion years. It’s currently 4.6 billion years old, so it’s basically having a mid-life crisis. This stability is why we’re here. We had the time to evolve because the Sun is "boring." It doesn't flicker much, it doesn't explode randomly, and it’s not going to run out of juice tomorrow.

Metallicity: The Secret Sauce

Here is something most people don't talk about: the Sun is "metal-rich."

In astronomy, anything heavier than Hydrogen or Helium is a "metal." The Sun has a higher concentration of these heavy elements than many older stars. This is because the Sun is a "Population I" star. It was born from the recycled remains of previous generations of stars that exploded and scattered heavy elements like carbon, nitrogen, and iron into space.

If the Sun didn't have these "metals," we wouldn't have rocky planets. No iron core for Earth means no magnetic field. No carbon means no people. When you look at the Sun compared to other stars in the older parts of the galaxy (Population II stars), those stars are mostly just hydrogen and helium. They might have gas giants, but they probably don't have many "Earths."

The Brightness Trap

If you look up at the night sky, you see stars like Sirius, Vega, and Rigel. You might think, "Wow, those are the normal stars."

Nope.

✨ Don't miss: Milwaukee 1/2 Impact: Why You Probably Don't Need the Most Expensive One

You’re seeing the celebrities. You only see them because they are insanely bright. Sirius is about 25 times more luminous than the Sun. Rigel is about 120,000 times more luminous.

If you were to line up all the stars in the galaxy by their actual brightness, the Sun would actually be brighter than about 85% of them. We just don't see the 85% because they’re too faint to spot without a telescope. It’s a classic case of survival bias. We think the universe is full of bright blue giants because those are the only ones that "shout" loud enough for us to hear them across the void.

Gravity and the Dance of Multiples

Most stars aren't loners.

The Sun is actually a bit of an introvert. About half of all sun-like stars are part of a binary or multiple-star system. Imagine having two suns in the sky like Tatooine. It sounds cool, but it’s a gravitational nightmare for planets. Orbiting a single star like ours is much "cleaner."

Systems like Alpha Centauri (our nearest neighbors) have three stars dancing around each other. Alpha Centauri A and B are a tight pair, while Proxima Centauri orbits them at a distance. Trying to maintain a stable, circular orbit for a planet in that kind of chaos is tricky. Our Sun’s solitary nature might be one of the key reasons life was able to flourish here.

What Happens When the Fuel Runs Out?

Every star dies, but they don't die the same way.

The Sun compared to other stars of higher mass will have a relatively peaceful exit. In about 5 billion years, it will swell up into a Red Giant. It’ll probably swallow Mercury and Venus, and maybe Earth (though the jury is still out on whether Earth's orbit will push out far enough to escape).

Then, it’ll shed its outer layers like a snake skin, creating a beautiful "planetary nebula." What’s left will be a White Dwarf—a hot, dense core about the size of Earth but with the mass of a star.

Massive stars? They go out with a bang. A supernova. They collapse so violently that they create a Black Hole or a Neutron Star. Our Sun isn't heavy enough for that. It doesn't have the "gravitational street cred" to become a black hole. It’ll just fade away over trillions of years until it becomes a cold, dark Black Dwarf.

Actionable Insights for Stargazers

If you want to actually see these differences for yourself, you don't need a PhD. You just need a clear night and a basic star map.

- Spot the "Twin": Look for Alpha Centauri A if you're in the Southern Hemisphere. It’s the closest thing we have to a "solar twin." It’s a G-type star just like ours. Looking at it is essentially like looking at our Sun from 4 light-years away.

- Observe the Color Contrast: Find Orion. Look at Betelgeuse (the reddish-orange one) and then look at Rigel (the blue-white one). That color difference is a direct measurement of their surface temperature. Rigel is thousands of degrees hotter than Betelgeuse.

- The Binocular Challenge: Try to find a red dwarf through binoculars. Even though they make up most of the universe, they are so faint that you have to know exactly where to look. It’ll give you a real sense of how "bright" our Sun actually is by comparison.

- Track the Sun’s Position: Use an app like Stellarium to see where the Sun sits on the Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) Diagram. You’ll see it right in the middle of the "Main Sequence," the long line where stars spend most of their lives.

Comparing our Sun to the rest of the cosmos reminds us that we live in a very specific, very stable pocket of reality. We aren't orbiting a monster that will explode tomorrow, and we aren't orbiting a dim ember that barely keeps us warm. We're orbiting a "top-tier" star that provided just the right conditions for everything you see around you.

Check the night sky tonight. When you see a tiny pinprick of light, remember: that "tiny" light might be a supergiant a thousand times bigger than our Sun, or our Sun might be ten times bigger than the star right next to it that you can't even see. Space is weird like that.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Download a Star Chart App: Use SkySafari or Stellarium to identify the "Spectral Class" of the stars you see. Look for the "G" class to find stars like our Sun.

- Visit a Local Observatory: Ask to see a Spectroscopy demonstration. This is how scientists actually know what stars are made of without ever visiting them.

- Research the "Solar Twin" project: Scientists are actively looking for stars that are identical to the Sun to find Earth-like planets. Check out the latest findings from the Kepler and TESS missions.