Everyone thinks they can build it in five minutes. It’s the "Hello World" of game development. You sit down, open a code editor, and think, "Alright, it's just a 3x3 grid, how hard can it be?" But honestly, when you actually try to design a tic tac toe game that people want to play more than once, you realize the logic is the easy part. The soul of the game? That’s where things get messy.

I’ve seen dozens of junior devs trip over this. They get the arrays working, the "X" and "O" toggle back and forth perfectly, and then... nothing. It feels like a spreadsheet. If your game feels like a tax return, you haven't designed a game; you've just built a data entry tool.

Why Most People Fail at Grid Logic

Let’s talk about the board. It’s not just a visual. It’s an array of nine integers, or strings, or whatever data type you're feeling today. Most beginners start with a flat array: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. It’s efficient. It’s clean. It’s also a nightmare for checking win conditions if you aren't careful with your math.

You have to check rows. You have to check columns. And don't forget those two pesky diagonals.

In a standard 3x3 setup, there are exactly eight ways to win. If you’re hard-coding these, you’re fine. But what happens if you want to scale? What if you want a 4x4 or a 5x5 board? This is where the design a tic tac toe game process separates the pros from the weekend hobbyists. Use loops. Seriously. Check for $n$ in a row where $n$ is your board width.

📖 Related: Why the Google Messages blue bubble is finally changing how we text

If you’re using JavaScript, you might be tempted to use a nested array like [[null, null, null], [null, null, null], [null, null, null]]. This maps better to the visual "mental model" of a grid. It makes the $x, y$ coordinates intuitive. But it adds complexity to your win-check loops. You're now iterating through arrays within arrays. It’s a trade-off. Do you want easy rendering or easy logic? Usually, the nested array wins for readability, even if it feels a bit bulkier.

The Secret Sauce: Feedback Loops

Ever played a game where you click a button and nothing happens for half a second? It’s infuriating. Even in a simple game like this, "juice" matters.

When a player clicks a square, they need to know the game heard them. This is basic UX, but it’s often ignored. A slight color change on hover. A "thud" sound when the "X" drops. A little animation where the symbol scales up from zero. These tiny details are what make the experience feel "physical."

Think about the "Draw" state. Most people just show a pop-up that says "Tie Game." Boring. Why not shake the whole board? Why not have the symbols crumble? If you want to design a tic tac toe game that actually sticks in someone's brain, you have to treat the UI like it’s made of material, not just pixels.

The AI Problem: Minimax or Random?

If you're building a single-player mode, you have a choice to make. You can make the AI a complete idiot that picks random empty squares, or you can make it a god-tier opponent that never loses.

The Minimax algorithm is the gold standard here. It’s a recursive function that looks at every possible future move and picks the one that leads to the best outcome. It’s perfect. It’s also kind of a jerk to play against. Because Tic Tac Toe is a "solved game," a perfect AI will always result in a draw or a win for the AI.

"Games are a series of interesting choices." — Sid Meier.

If the player can't win, the choices aren't interesting. They're futile.

When you design a tic tac toe game, you should probably include a "difficulty" setting. On "Easy," let the AI pick randomly 50% of the time. On "Hard," let it use the Minimax logic. This gives the player a sense of progression. They can beat the "Dummy" bot, feel good about themselves, and then get humbled by the "Grandmaster" bot.

Managing State Without Losing Your Mind

State management is where the bugs hide. You need to track:

- Whose turn it is (usually a boolean:

isXNext). - The current board configuration.

- Whether there’s a winner.

- A history of moves (if you want an "Undo" button).

If you’re using a framework like React, don't overcomplicate this with Redux or some massive library. Use useState. Keep the board state at the top level and pass it down to the individual "Square" components. This is called "lifting state up," and it's the only way to ensure your board doesn't get out of sync with your "Winner" announcement.

One common mistake? Forgetting to disable the board after someone wins. There’s nothing weirder than being able to keep placing "O"s after the "X" has already lined up three in a row. It breaks the magic. Lock the state. Freeze the inputs.

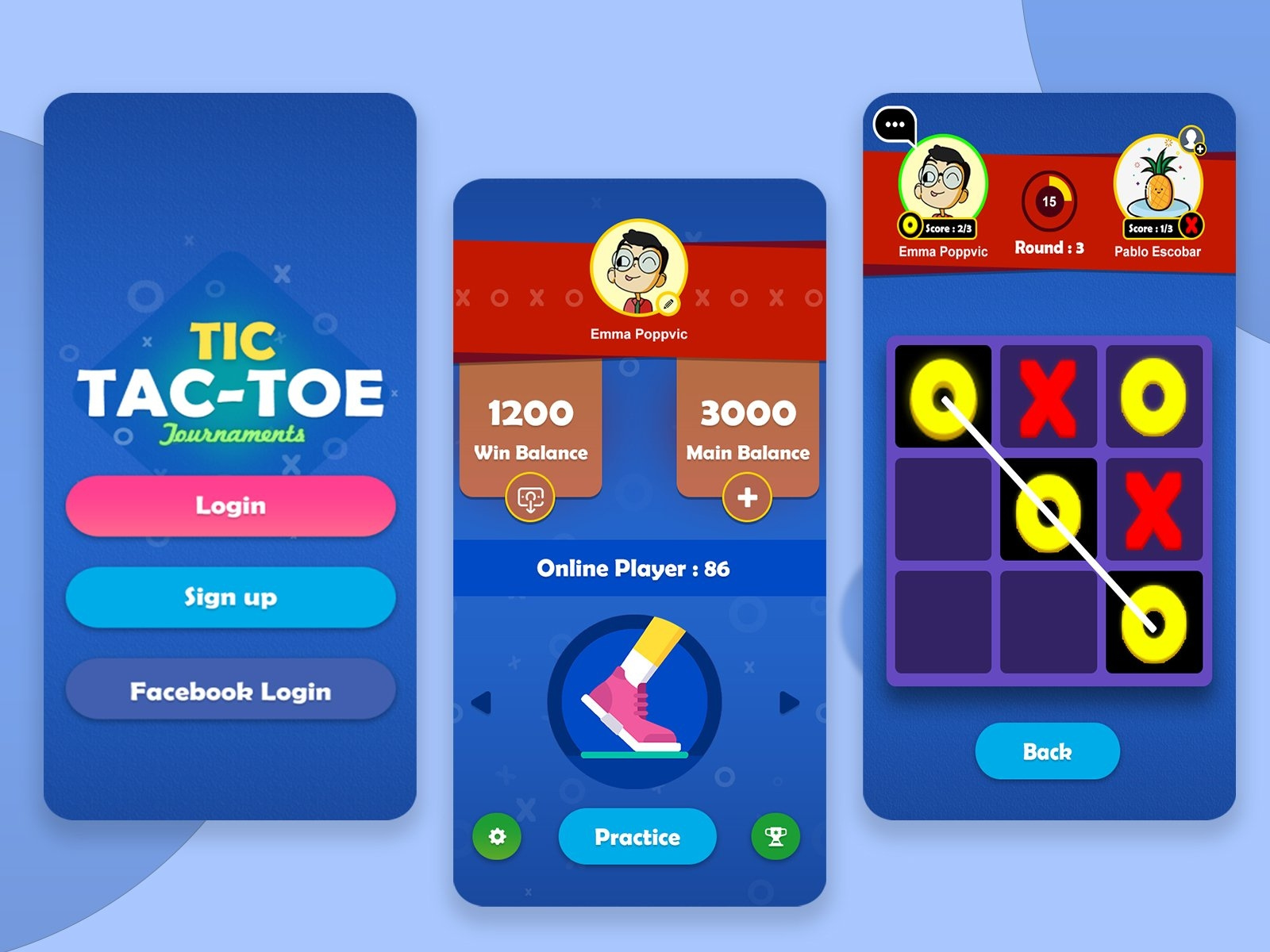

The Technical Reality of Mobile Design

If this game is going to live on a phone, those squares need to be big. Fat-finger syndrome is real.

If your grid is too small, people will accidentally tap the wrong square, get mad, and close the tab. Make the grid responsive. Use CSS Grid—it’s literally built for this. A simple grid-template-columns: repeat(3, 1fr); will give you a perfect 3x3 layout that scales with the screen size.

Also, consider the "Game Loop." In a 3x3 game, the play session lasts about 20 seconds. You need a "Play Again" button that is front and center the moment the game ends. Don't make them refresh the page. That’s a friction point that kills retention.

Beyond the 3x3: Variants That Actually Work

If you find the base game too simple, you can spice it up. I’ve seen some wild variations. There’s "Ultimate Tic Tac Toe," where each square in the 3x3 grid is itself a smaller 3x3 grid. To win a square on the big board, you have to win the small game inside it.

It’s inception-style game design.

Then there’s the "vanishing" variant. After a player places their fourth piece, their first piece disappears. This prevents draws entirely and forces players to think several moves ahead. When you design a tic tac toe game with these twists, you aren't just making a clone; you're making a new experience.

Actionable Steps for Your First Build

Don't overthink the start. Just build.

- Sketch the Logic: Write out the win conditions on paper. It sounds old-school, but visualizing the index numbers

[0,1,2],[3,4,5], etc., helps prevent off-by-one errors later. - Pick Your Stack: If you want it on the web, HTML/CSS/JS is fine. If you want a desktop app, try Python with the Pygame library.

- Build the Grid First: Don't worry about the AI or the "X"s yet. Just get nine squares on the screen that change color when you click them.

- Implement the Win Check: Create a function that runs after every single move. If it finds a winner, stop the game.

- Add the "Juice": Spend at least an hour on CSS transitions or sound effects. This is what makes it feel like a "game" instead of a school project.

- Refactor for Scale: Once it works, try changing the code so it can handle a 4x4 grid. This will force you to write better, more modular logic.

The beauty of this project is that it’s finite. You can start at 9:00 AM and have a playable, polished product by lunchtime. Just remember that the user doesn't care about your clean code; they care about how it feels when they finally trap the AI in a double-threat win scenario. That "Aha!" moment is why we build games in the first place.

Start with a single div. Add a click listener. The rest is just details. Once the basic logic is solid, focus on the "Game State" transitions—how the screen looks between the title menu, the active game, and the victory screen. A smooth transition between these states makes the application feel professional. Use a simple state machine logic: IDLE, PLAYING, WON, DRAW. This keeps your code organized and prevents weird edge cases where the game thinks it's still running while the "Game Over" screen is visible.

Lastly, test it on a real person. Watch them play. If they hesitate or look confused, your UI needs work. Usually, the simplest fix is the best one. Bigger buttons, clearer colors, and faster animations. That's the secret to a successful build.