You’ve probably seen them. Those neon-green curtains of light dancing over a suburban backyard or a deep-red glow that looks like the sky is literally on fire. These images of solar storm events have been flooding social media lately, especially since we’re currently riding the peak of Solar Cycle 25. Everyone has a high-res camera in their pocket now. But here’s the thing: what you see on your screen isn't always what you'd see with your naked eyes. It’s actually a bit of a tech illusion.

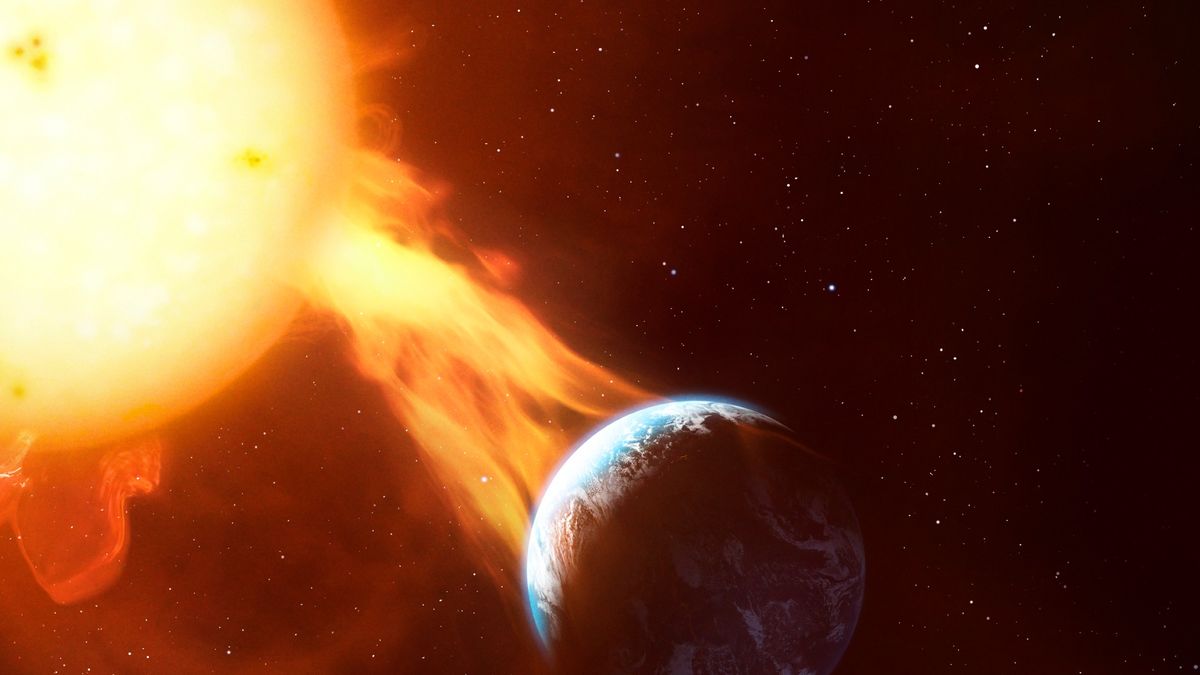

Space is messy. The sun isn't just a static ball of light; it’s a churning, magnetic beast that occasionally burps out billions of tons of plasma. When that plasma hits Earth's magnetic field, we get the visuals.

Why Images of Solar Storm Impacts Look "Fake" (But Aren't)

Most people get disappointed when they go outside during a G4-rated storm. They expect the vibrant, electric purples they saw on Instagram. Instead, they see a faint gray mist. Why? Because your phone is better at seeing the universe than you are.

Modern CMOS sensors in smartphones are incredibly sensitive to long-wavelength light. When you take a photo of an aurora, the "Night Mode" gathers light for three to ten seconds. It stacks photons. Your eye, meanwhile, refreshes its "frame rate" much faster and lacks the long-exposure capability to soak up those faint colors. Basically, the camera is a time-traveler that bundles ten seconds of light into one single image. That's why those images of solar storm auroras look like someone cranked the saturation to 100.

📖 Related: New Emojis: What Really Happened to the Apple Core

The Physics of the Glow

It’s all about the gas. When solar particles slam into our atmosphere, they excite different elements.

- Green: This is the most common. It’s oxygen at lower altitudes—about 60 to 150 miles up.

- Red: Rare and beautiful. This is oxygen too, but at much higher altitudes (up to 200 miles).

- Blue/Purple: That’s nitrogen getting smacked around.

If you see a photo with deep crimson at the top, you’re looking at a high-energy event. If it’s just a murky green, it’s a standard Tuesday in the magnetosphere.

The Most Famous Photos in History

We can’t talk about solar imagery without mentioning the 1859 Carrington Event. We don't have photos of that—photography was in its infancy—but we have sketches. Detailed, frantic drawings by Richard Carrington. He saw two patches of "intense white light" break out from a group of sunspots.

Fast forward to 2003. The "Halloween Storms." This was a game-changer for NASA’s SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory). The images of solar storm activity from that period show a "snowstorm" effect on the camera sensor. That "snow" wasn't weather; it was high-energy protons physically striking the camera's detector. It’s essentially a photo of radiation hitting a lens.

Then there was May 2024. This was a generational event. For the first time in decades, people in Florida and Mexico were capturing auroras on their iPhones. It proved that solar activity isn't just a "North Pole" thing anymore. It's a global phenomenon that can be captured by anyone with a tripod and a bit of patience.

It’s Not Just Pretty Lights

Real experts—the folks at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC)—don't look at these photos for the aesthetics. They look at them for the data. When we see images of solar storm activity captured by the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), we're looking at specific wavelengths of ultraviolet light.

💡 You might also like: The Date of Moon Landing: Why July 20, 1969, Still Breaks the Internet

These images tell us about the magnetic "knots" on the sun's surface. Think of it like a rubber band. If you twist a rubber band enough, it eventually snaps. That "snap" is a solar flare. If it’s big enough, it launches a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME). That’s the "cloud" of stuff that actually travels through space to hit us.

How to Spot a "Real" Solar Photo vs. AI

Honestly, the internet is full of junk now. AI-generated space photos are everywhere. If you’re looking at images of solar storm events and the stars look like perfect little crosses, or the aurora looks like a literal silk curtain with perfectly straight edges, it’s probably fake.

Real auroras are chaotic. They have "beading" and "fringing." They look a little bit blurry because, well, the atmosphere is moving. If a photo looks too perfect, check the source. NASA, ESA, and reputable astrophotographers like Thierry Legault or Alan Dyer are the gold standards.

The Risks Behind the Beauty

We love the photos, but the reality of a massive solar storm is kinda terrifying. In 1989, a solar storm knocked out the power grid in Quebec. Six million people were in the dark for nine hours.

When you see a photo of a particularly bright aurora, you're actually looking at a massive electrical discharge. This energy can induce currents in our power lines. It can fry the delicate electronics in GPS satellites. If we had a Carrington-level event today, your phone wouldn't just be taking photos of the storm; it might stop working entirely. The "internet apocalypse" is a bit of a sensationalist term, but the risk to undersea fiber optic cables is a real topic of study among researchers like Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi.

Capturing Your Own Images

If a G3 or G4 storm is predicted, don't just stand there.

- Get away from city lights. Light pollution is the enemy of the aurora.

- Use a tripod. Even a cheap one. You cannot hold a phone steady for 5 seconds.

- Manual Focus. Set your focus to "infinity." If your phone keeps trying to focus on the dark sky, the photo will be a blurry mess.

- Raw Format. If your phone supports it, shoot in RAW. It preserves the data that your phone’s software usually throws away to make the file smaller.

Where to Find Live Feeds

You don't have to wait for a viral tweet. You can see images of solar storm precursors in real-time. The SDO (Solar Dynamics Observatory) website has a "The Sun Now" section. It updates every few minutes with images in different angstroms (wavelengths).

- 171 Angstroms: Shows the "coronal loops"—the magnetic structures.

- 304 Angstroms: Shows the cooler gas and filaments.

- HMI Continuum: This is what the sun looks like in visible light. This is where you look for sunspots.

Sunspots are the "batteries" of solar storms. If you see a massive cluster of black spots in the center of the solar disk, get your camera ready. It usually takes about two to three days for a CME to travel from the sun to the earth.

🔗 Read more: Outdoor Sound System Wireless Tech: Why Most People Waste Their Money

The Science of the "Light"

What we call light is just a tiny slice of the spectrum. When satellites take images of solar storm events, they often look into the X-ray and Extreme Ultraviolet ranges. Human eyes can't see this. We color-code them so we can understand what's happening.

If a NASA photo of the sun is bright green, that doesn't mean the sun is green. It means the scientists have assigned green to a specific wavelength of UV light to make the details pop. It’s a tool for visualization, not a literal representation. This nuance is something most casual viewers miss. They think the sun is a disco ball of different colors. It's actually a blindingly white star that we filter for our own benefit.

Actionable Steps for the Next Big Storm

Instead of just scrolling through images of solar storm events online, get prepared to document the next one yourself. The sun is approaching the "Solar Maximum" phase of its cycle, meaning 2025 and 2026 will likely be the best years for aurora hunting in a decade.

- Download a Space Weather App: Apps like "Aurora Forecast" or "My Aurora Forecast" use NOAA data to give you "Kp-index" alerts. A Kp-index of 5 is a minor storm; a Kp-index of 9 is a massive, once-in-a-decade event.

- Check the "Bz" Component: If you look at solar data, look for the "Bz." It represents the north-south direction of the interplanetary magnetic field. If the Bz is "South" (negative), the solar wind can "hook" into Earth's magnetic field more easily, creating much brighter images.

- Practice Long Exposure Now: Don't wait for a storm to learn how to use your camera's night mode. Practice on the stars tonight. Learn how to toggle your flash off—nothing ruins an aurora photo faster than a phone flash hitting a nearby tree.

- Watch the Coronal Holes: Keep an eye on the solar wind speed. High-speed streams from coronal holes can cause beautiful, long-lasting auroras even without a major solar flare.

The sun is restless. We are just beginning to see the full power of this solar cycle. Keep your eyes on the data and your camera on a tripod. The best images of solar storm history are probably going to be taken in the next 24 months.