You’re standing in a lab—or maybe just your kitchen—trying to figure out why your sourdough starter isn't rising. You change the flour. You wait. Nothing. Then you change the temperature. Still nothing. The problem isn't your baking; it’s your logic. You’re messing with too many things at once. In the world of formal research, what you’re fiddling with is called the independent variable, and honestly, it is the only thing in an experiment that you actually have total control over.

It’s the "cause."

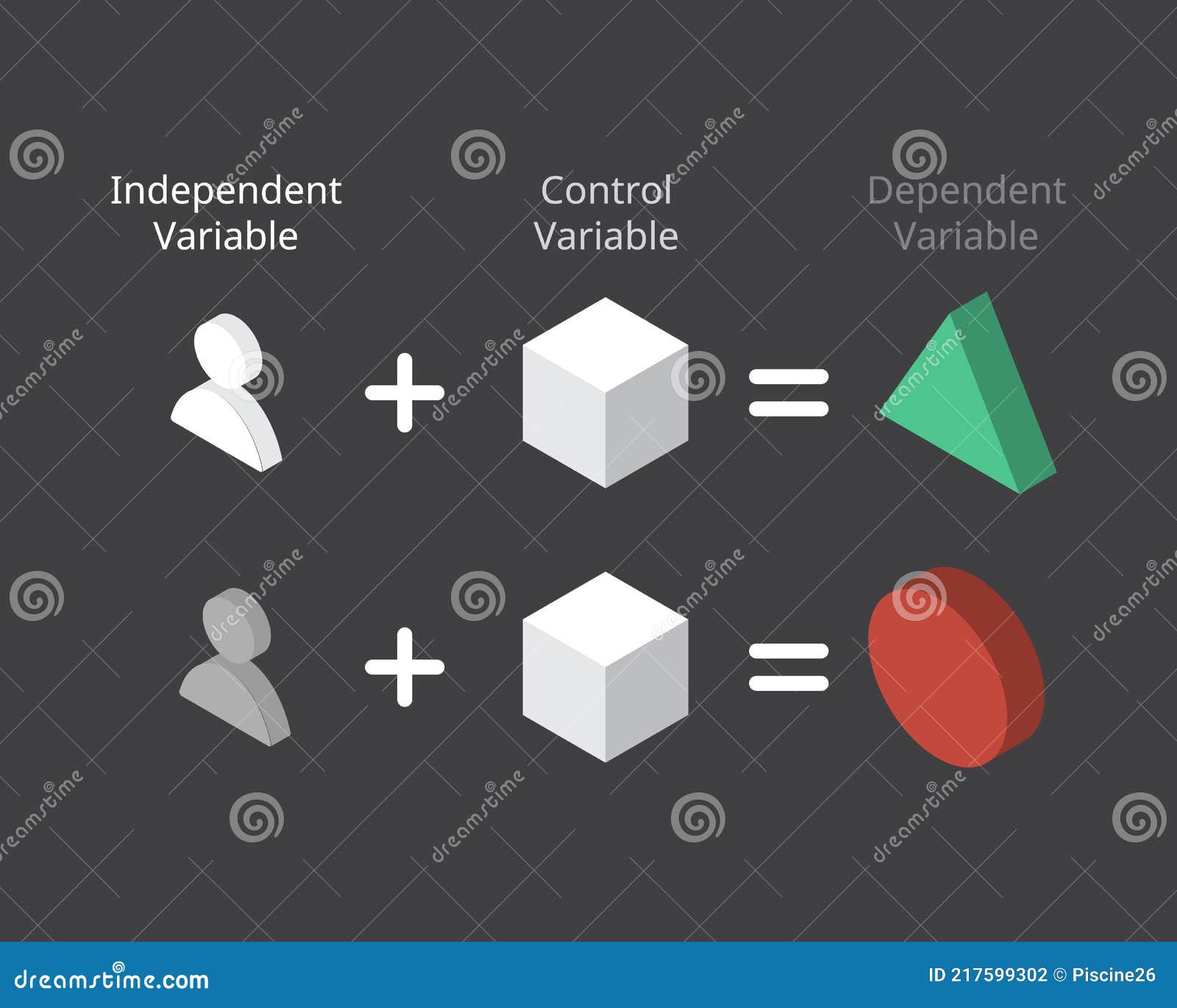

If you’ve ever wondered why some scientific studies seem like total nonsense while others change the world, it usually comes down to how they handled this one specific factor. The independent variable in an experiment is the input you intentionally manipulate to see if it triggers a change somewhere else.

Why the Independent Variable is the Boss of the Lab

Think of the independent variable as the driver of a car. The car goes where the driver turns the wheel. In a study looking at how caffeine affects heart rate, the caffeine is your independent variable. You decide the dose. You decide who gets it. The heart rate? That’s just reacting. It’s the follower.

Scientists often call the independent variable the "predictor" or the "treatment" variable. If you’re reading a peer-reviewed paper in Nature or The Lancet, you might see it referred to as the "exogenous" variable. That’s just a fancy way of saying it comes from outside the system you're measuring. You, the researcher, are shoving it into the mix to see what breaks or what blooms.

Most people get tripped up because they try to track too many independent variables at once. This is a nightmare. If you give a plant more water and more sunlight at the same time, and it grows three inches, which one did the work? You don't know. You’ve created a "confounding variable" situation, which is basically the junk mail of the science world. To get a clean result, you usually want one primary independent variable per experimental trial.

The "If-Then" Logic That Actually Works

The easiest way to spot the independent variable in an experiment is to plug your research question into an "If-Then" statement.

If I change [Independent Variable], then I will observe a change in [Dependent Variable].

Let’s look at a real-world tech example. A UI designer at a company like Spotify wants to know if a neon green "Play" button gets more clicks than a grey one.

- The Independent Variable: The color of the button.

- The Dependent Variable: The number of clicks.

The designer has 100% control over that color. They can make it hot pink, neon green, or "sad-office-beige." But they have zero direct control over whether a user actually clicks it. They can only influence the user by twisting the knob of the independent variable.

Experimental vs. Quasi-Experimental Variables

Here is where things get a bit messy. Not every independent variable is something you can actually "do" to someone.

In a true experiment, you use random assignment. You pick a name out of a hat and say, "You’re getting 50mg of this new vitamin." That is a manipulated independent variable. But what if you want to study how "years of smoking" affects lung capacity? You can’t ethically force a group of people to smoke for twenty years just for your data.

In those cases, researchers use "subject variables" or "quasi-independent variables." These are traits that participants already have when they walk into the room—like their age, their height, or their pre-existing habits. You’re still treating it as the "cause," but you didn't create it. You’re just sorting people based on it.

✨ Don't miss: New Gadgets for Guys That Actually Solve Problems (Not Just Collecting Dust)

The Headache of Levels and Groups

When you define the independent variable in an experiment, you also have to define its "levels." This sounds complicated, but it’s just the different values you're testing.

If you're testing a new fertilizer, your levels might be:

- No fertilizer (the Control Group)

- 5 grams of fertilizer

- 10 grams of fertilizer

The variable is still just "amount of fertilizer," but it has three levels. Without a control group—that "zero" level—your experiment is basically guessing. You need a baseline to prove that your independent variable is actually doing something and that the plants didn't just grow because, well, plants like to grow.

Real World Nuance: When Variables Get Ghosted

Sometimes, the independent variable you think you’re measuring isn't the one doing the work. This is the "Placebo Effect" in a nutshell.

In a classic 1920s study at the Hawthorne Works factory, researchers wanted to see if better lighting (the independent variable) would improve worker productivity (the dependent variable). They turned the lights up. Productivity went up. They turned the lights down. Productivity... went up again?

It turned out the independent variable wasn't the light level at all. It was the fact that the workers knew they were being watched. This is why expert researchers are obsessed with "blinding" and "double-blinding." They want to make sure the independent variable is the only thing changing between groups.

How to Set Up Your Own Variables Without Failing

If you’re designing a test—whether it’s for a high school science fair, a marketing A/B test, or a clinical trial—you need to follow a few hard rules.

First, Operationalize it. Don’t just say your independent variable is "exercise." That’s too vague. Is it "30 minutes of treadmill running at 6mph"? Is it "lifting weights until failure"? If you can’t measure it with a number or a specific category, it’s a bad variable.

Second, Keep it Independent. This sounds obvious, but it’s the most common mistake. Your independent variable should not be affected by other variables in the study. If you’re testing how "heat" affects "ice melting," but your heat source is a lamp that also introduces "wind," your variable is no longer independent. It’s contaminated.

Third, Watch for the "Ceiling Effect." This happens when your independent variable is too strong. If you give someone 1,000mg of caffeine, they’re going to be jittery regardless of their personality, age, or health. You might miss the subtle nuances because you cranked the "cause" up to eleven.

Actionable Steps for Defining Your Variables

Before you start collecting data, run your experiment through this checklist.

- Identify the 'Knob': What is the one thing you are turning up or down? If you have two knobs, you have two experiments.

- Establish the Baseline: Do you have a group that is getting "zero" of the independent variable? If not, you’re just observing, not experimenting.

- Check for Ethics: If your independent variable is "stress," how are you inducing it? If it’s "sleep deprivation," how long is safe?

- Write the Equation: $y = f(x)$. In this classic math setup, $x$ is your independent variable. It’s the input. $y$ is the result. If you can't plot your experiment on a graph where $x$ changes and $y$ responds, you need to go back to the drawing board.

To truly master the independent variable in an experiment, you have to be willing to be wrong. Sometimes you change the variable and nothing happens. That’s actually great. It means you’ve ruled something out. In science, a "null result" is just as valuable as a breakthrough. It tells you that the "cause" you suspected isn't the real driver.

Next time you see a headline claiming "Chocolate causes weight loss," look for the independent variable. How much chocolate? What kind? Was it the chocolate, or was it the fact that the participants were also told to run five miles a day? When you find the independent variable, you find the truth of the study.

Stop guessing. Start isolating. The more you control the "why," the better you'll understand the "what." This is how progress happens—one variable at a time.