You're sitting in a stadium. The crowd starts "The Wave." It ripples around the arena, people jumping up and sitting down in a vertical motion while the pulse itself travels horizontally. That right there is a transverse wave. But then you scream at the top of your lungs because your team scored. Is that scream doing the same thing? People often ask is sound a transverse wave, usually because they’ve seen a jagged line on a heart monitor or a music editing program and assumed that's what sound "looks" like.

It isn't.

If you’re looking for the short answer: No. In air and water, sound is a longitudinal wave. It’s a series of shoves. It’s more like a Slinky being pushed and pulled than a rope being shaken up and down. But, as with anything in physics, there is a "but." If you start talking about sound traveling through a diamond or a hunk of steel, things get weird.

Why We Get Confused: The Oscilloscope Trap

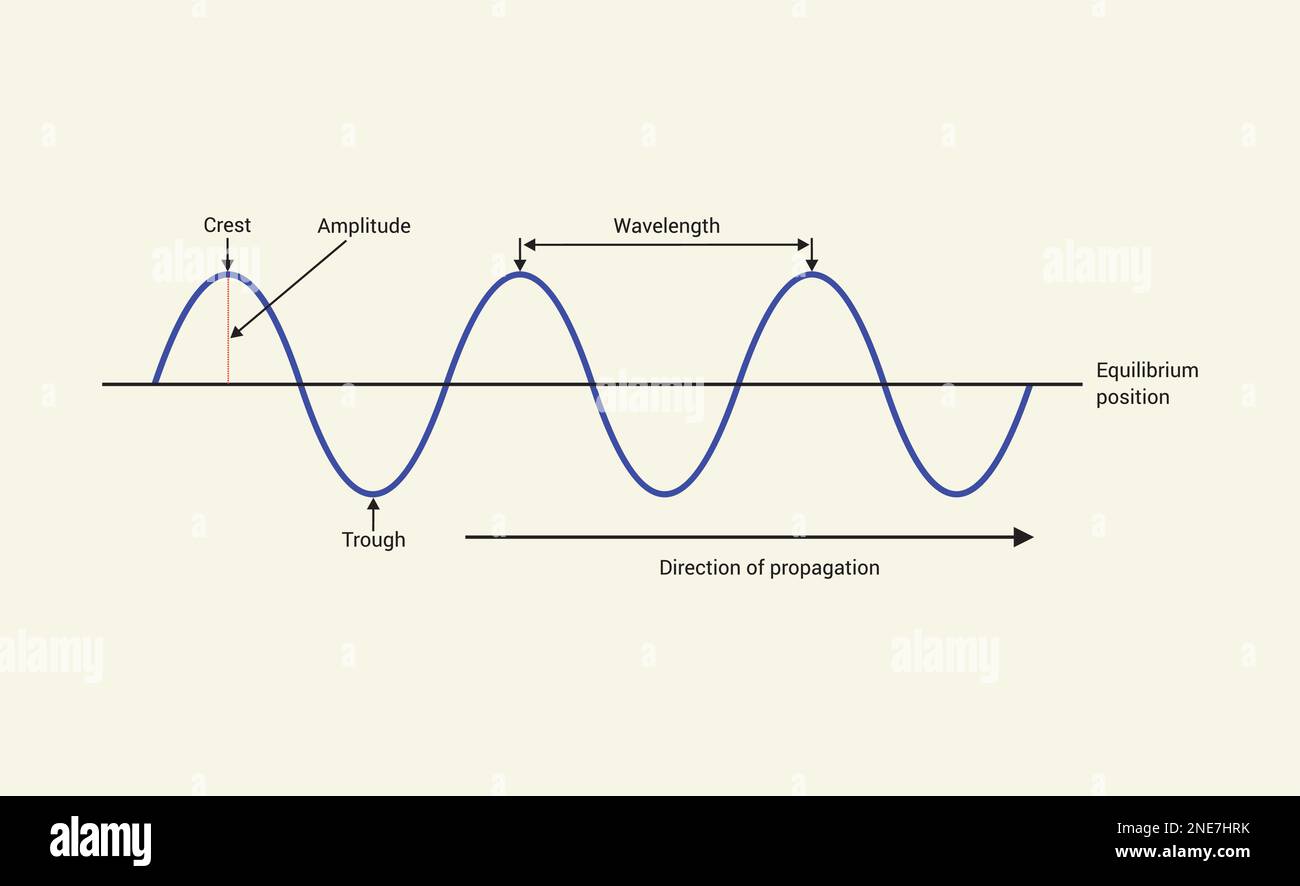

Most of us think sound is transverse because we’ve been lied to by visuals. Think about every "sound wave" graphic you’ve ever seen. It’s a squiggly line. In physics terms, that’s a sine wave. Because that line moves up and down while the wave moves left to right, it looks transverse.

But that graph is just a map. It’s a representation of pressure. When the line goes up, the air molecules are packed tight (compression). When the line goes down, they’re spread out (rarefaction). The air isn't actually jumping up and down; it’s pulsing forward and backward. We just draw it as a transverse wave because, honestly, trying to draw thousands of tiny dots bumping into each other is a nightmare for a textbook illustrator.

The Mechanics: How Longitudinal Waves Actually Work

In a longitudinal wave, the particles of the medium move parallel to the direction the energy is traveling. Imagine a crowded line at a grocery store. If someone at the back shoves the person in front of them, that shove travels to the front of the line. Each person moves forward and then back to their original spot. Nobody swapped places permanently. The "shove" moved; the people stayed.

Sound works exactly like that. When a speaker cone vibrates, it smacks the air molecules right in front of it. Those molecules whack the ones in front of them and then bounce back. This creates high-pressure zones called compressions and low-pressure zones called rarefactions.

The Speed Factor

The speed of these shoves depends entirely on what they’re moving through. In dry air at 20°C, sound travels at about 343 meters per second.

If you dive underwater, it’s much faster—roughly 1,480 meters per second. Why? Because water is harder to compress. The molecules are closer together, so they don’t have to travel as far to "tag" their neighbor. It’s like playing telephone in a crowded room versus a big empty field.

Is Sound Ever Transverse? The Solid Exception

Here is where the "expert" answer gets nuanced. While sound in fluids (air, gases, liquids) is strictly longitudinal, solids are a different story.

When sound moves through a solid, like a seismic wave through the Earth's crust or a vibration through a steel beam, it can actually manifest as both longitudinal and transverse waves. In seismic science, we call these P-waves (Primary) and S-waves (Secondary).

- P-waves are longitudinal. They are fast. They get there first.

- S-waves are transverse. They move the ground up and down or side to side. They are slower, but they usually do more damage.

So, if you’re standing on a massive block of granite and someone hits the other side with a sledgehammer, the "sound" traveling through that rock is actually a mix of both types of waves. But for 99% of human experience—talking, listening to Spotify, hearing a car horn—sound is purely longitudinal.

The Role of Frequency and Amplitude

We can't talk about the nature of the wave without mentioning what makes sound actually sound like... well, sound.

Frequency is how many of those "shoves" happen per second. We measure this in Hertz (Hz). A high-pitched whistle has thousands of compressions hitting your eardrum every second. A low bass note has fewer, but they're often more powerful.

Amplitude is the "bigness" of the shove. It’s the pressure difference. If you whisper, you’re barely nudging the air. If you set off a firework, you’re creating a massive, sudden wall of high pressure. This is what we perceive as volume.

Why This Matters for Technology

Understanding that sound is longitudinal is vital for engineering. Microphones are designed specifically to catch these pressure changes. A diaphragm in a mic works just like your eardrum—it gets pushed in by the compression and pulled out by the rarefaction.

If sound were transverse, microphones would have to be built entirely differently. They would need to detect "shear" forces—the sliding movement of air—rather than the direct "pumping" of pressure.

In the world of ultrasound imaging, doctors rely on the longitudinal nature of sound to map the body. The machine sends out a pulse and waits for it to bounce back. Because sound behaves predictably as a longitudinal wave in the "liquid" environment of the human body, the computer can calculate distances with incredible precision. If the wave were flopping around transversely, the image would be a blurry mess.

Breaking Down the "Acoustic" Myths

You might hear people talk about "transverse sound" in the context of surface waves on a drum skin. While the drum skin itself is moving transversely (up and down), the sound it pushes into the air is longitudinal.

It's a chain reaction.

- The drum stick hits the skin.

- The skin moves up and down (Transverse).

- The skin hits the air molecules (Longitudinal).

- Your ear processes the pressure (Sound).

Practical Takeaways for Sound Enthusiasts

If you're a producer, a student, or just a nerd about how the world works, keep these points in your back pocket:

💡 You might also like: iPhone 15 Pro Max trade in: Why you’re probably getting lowballed and how to fix it

- Air and Water: Sound is always longitudinal. It’s a pressure wave, not a wiggle wave.

- Solids: This is the only place sound can "become" transverse (S-waves).

- Visualization: Don't let the "squiggly line" on your screen fool you. That's just a graph of pressure over time.

- Room Treatment: If you’re trying to soundproof a room, you aren't stopping "waves" that look like ropes; you’re trying to absorb or scatter "pulses" of air pressure.

To truly understand acoustics, you have to stop thinking about sound as a "thing" that travels and start thinking about it as something that happens to the air. It’s a collective behavior of molecules.

To see this in action without a lab, grab a Slinky. Have a friend hold one end. Stretch it out. If you shake your hand up and down, you’ve made a transverse wave. Now, instead of shaking, give the Slinky a sharp shove toward your friend. Watch that pulse travel down the coils. That is sound. That is a longitudinal wave.

The next time someone asks is sound a transverse wave, you can confidently tell them that unless they are living inside a block of solid iron, the answer is a resounding no. Understanding this distinction is the first step toward mastering everything from high-end audio engineering to the fundamental laws of physics.

Actionable Next Steps

- Check your gear: If you're a musician, look at your speaker cones while playing a low frequency. Notice they move "in and out" (longitudinal) rather than side to side.

- Seismic Research: If you're interested in the "solid" exception, look up the difference between P-waves and S-waves in earthquake data. It’s the best real-world example of transverse "sound" in solids.

- Phase Correction: In home theater setups, realize that "phase" issues happen because these longitudinal pulses are hitting each other at the wrong time, canceling out the pressure.