Everything is connected. You’ve heard that before, right? Usually, it's some hippie-dippie sentiment about the "circle of life" or how your morning coffee affects a butterfly in Brazil. But in the cold, hard world of thermodynamics, "everything is connected" is actually a huge headache. It makes calculating how energy moves through a engine or a star incredibly messy.

To solve this, scientists came up with a bit of a cheat code. They invented the concept of an isolated system.

It’s a simple idea on paper. An isolated system is a physical system so far removed from its environment that absolutely nothing gets in or out. No heat. No light. No atoms. No stray cosmic rays. It’s the ultimate "do not disturb" sign. But here’s the kicker: in the real world, a truly isolated system doesn't actually exist.

Everything leaks.

What is an isolated system anyway?

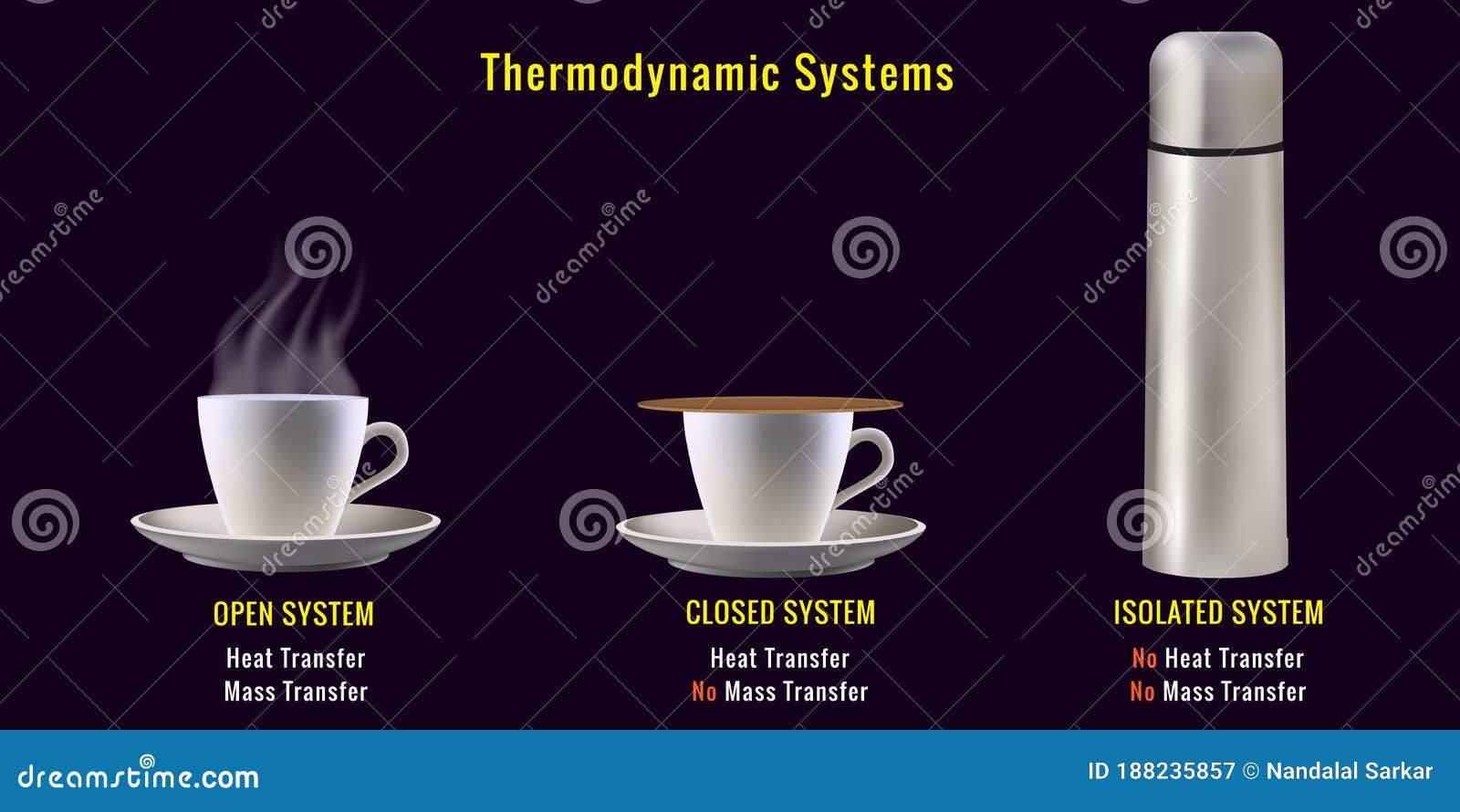

Let’s get the textbook definition out of the way before we get into why it’s a lie. In physics, we categorize systems based on how they interact with their surroundings. You've got open systems, like a boiling pot of water where steam escapes and heat flows in from the burner. Then you’ve got closed systems, which can swap energy (like heat) but don't let matter pass through—think of a sealed pressure cooker.

Then there is the isolated system.

Imagine a box. This box is perfectly insulated. It doesn't let heat escape, and it doesn't let external cold seep in. It’s also perfectly sealed, so no gas or liquid can leak out. But it goes further than that. To be truly isolated, even the gravitational pull or electromagnetic fields of the outside world shouldn't affect what’s inside.

$$dQ = 0$$

$$dW = 0$$

$$dn = 0$$

In these equations, $Q$ is heat, $W$ is work, and $n$ is the amount of matter. In an isolated system, the change in all these values is zero. Total energy remains constant. Entropy—the measure of disorder—can only go up or stay the same. It can never go down.

The thermos bottle trap

People often point to a vacuum flask—you know, a Thermos—as the go-to example of an isolated system. It’s got double walls with a vacuum in between to stop conduction and radiation. It keeps your soup hot for hours.

But it’s not isolated. Not even close.

If you leave that soup there for three days, it’s going to be cold. Heat eventually radiates through the glass or leaks through the stopper. Gravity is still pulling on the liquid inside. If you hold a magnet to the side of the flask, the magnetic field passes right through the "isolation."

💡 You might also like: Orange County Movie Streaming: Why Your Local Connection Still Matters More Than Netflix

We call it isolated for the sake of a high school chemistry experiment because, over the span of ten minutes, the energy loss is negligible. It’s a "close enough" approximation. Scientists love approximations. Without them, the math would be so complex that we’d never get anything built.

The only real example is... everything?

If you want to find a truly isolated system, you have to look bigger. Much bigger.

Most cosmologists, like Sean Carroll or the late Stephen Hawking, have argued that the only truly isolated system in existence is the entire universe itself. Think about it. If the universe is everything that exists, there is no "outside" for energy or matter to escape to. There’s no neighbor to trade heat with.

Inside the universe, energy is constantly shifting. Stars explode, planets cool, and you eat a sandwich. But the total sum of energy? That stays the same. The universe is the ultimate closed-loop.

Why the Second Law of Thermodynamics ruins the party

You can’t talk about these systems without mentioning entropy. It’s the "tax" of the universe.

In an isolated system, things naturally move toward a state of maximum chaos. This is the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Because no new energy can come in to "tidy things up," the system eventually reaches what we call thermodynamic equilibrium.

Think of a bedroom. If you never enter the room to clean it (adding energy from the outside), it stays messy. But it’s worse than that. In a truly isolated room, the molecules would eventually spread out until the temperature is perfectly uniform everywhere. No hot spots, no cold spots. Just a lukewarm, gray soup of nothingness.

When an isolated system reaches this state, it’s effectively dead. No more work can be performed. This is the "Heat Death" theory of the universe. If the universe is isolated, eventually all the stars will burn out, all the heat will even out, and nothing will ever happen again. Ever.

Kinda bleak, honestly.

Practical uses for a fake concept

If isolated systems don't exist, why do we bother teaching them in every university physics track from MIT to Stanford?

Because of "Idealization."

Engineers use the concept to set the upper limit of efficiency. If you're designing a new type of battery or a nuclear reactor, you start by calculating how it would behave as an isolated system. This gives you the theoretical maximum performance. Then, you work backward and account for the "real world" losses—friction, heat bleed, material degradation.

- Calorimetry: When chemists want to measure how much energy is in a peanut, they burn it inside a "bomb calorimeter." They treat the water jacket around the combustion chamber as an isolated system to ensure the temperature rise they measure is strictly from the peanut.

- Quantum Computing: This is where it gets techy. A quantum bit (qubit) is incredibly fragile. If a single photon from the outside world hits it, the data is lost—a process called decoherence. Engineers at companies like IBM and Google are essentially trying to build the world's most perfect isolated system to keep these qubits "quiet."

- Spacecraft: In the vacuum of space, a ship is almost isolated. There’s no air to carry heat away via conduction. However, radiation from the sun still hits it, and the ship still radiates infrared heat back out.

The nuance of "Partial Isolation"

Often, we talk about isolation in terms of specific properties rather than a total blackout.

You might have a system that is "thermally isolated" but not "mechanically isolated." Maybe you have a piston inside an insulated cylinder. Heat can't get out, but the piston can move up and down, doing work on the outside world.

This is where the distinction gets blurry. In the lab, we use things like Faraday cages to block electromagnetic interference. We use vibration isolation tables to stop the rumble of a passing truck from ruining a laser experiment. We’re constantly trying to "isolate" variables, even if we can't isolate the entire system.

Misconceptions to clear up

A lot of people confuse "vacuum" with "isolation."

Just because there is a vacuum doesn't mean a system is isolated. Light travels through a vacuum. Gravity travels through a vacuum. If you put a hot iron bar in a vacuum chamber, it will still cool down because it emits infrared radiation. To be an isolated system, you’d need to line that vacuum chamber with perfect mirrors that reflect 100% of all radiation back inward—and we don't have those.

How to use this knowledge

Understanding the limits of an isolated system changes how you look at efficiency and sustainability. Whether you’re an engineer, a student, or just someone curious about how the world works, the takeaway is the same:

- Stop looking for 100% efficiency. It’s physically impossible because you can never perfectly isolate a process from its environment.

- Focus on the "boundary." In any project, the most important part is where the system meets the world. That’s where you lose money, heat, and data.

- Account for entropy. If you are managing a project or a piece of hardware, remember that without an external energy input (maintenance), the system will naturally slide toward disorder.

To really wrap your head around this, try identifying the "boundaries" in your daily life. Your house is a system—how does it swap matter and energy with the street? Your car is a system. Even your body is an open system, constantly exchanging air, food, and heat.

The closer you look, the more you realize that the isolated system is a beautiful, necessary, and entirely fictional dream of science. It’s the "frictionless plane" of thermodynamics. We need it to make sense of the math, but we should never forget that in reality, the walls are always a little bit porous.

Next Steps for Deep Learning

To see these principles in action, look into the Carnot Cycle. It’s the theoretical limit for heat engines and shows exactly why the lack of perfect isolation limits every engine ever built. You might also want to explore Boltzmann’s Entropy Formula, which provides the mathematical bridge between the microscopic movement of atoms and the macroscopic "leakiness" of the systems we build today.