If you ask anyone over the age of seventy where they were when history changed, they won't hesitate. They’ll tell you about a grainy black-and-white screen. They’ll mention the static. Most importantly, they’ll give you a specific day. But depending on where they lived in 1969, that day might actually be different.

The date Apollo 11 landed on moon was July 20, 1969. That is the "official" answer. However, if you were sitting in a pub in London or waking up in Tokyo at the time, the moonwalk didn't actually happen until July 21. Time zones are a headache, even when you're leaving the planet.

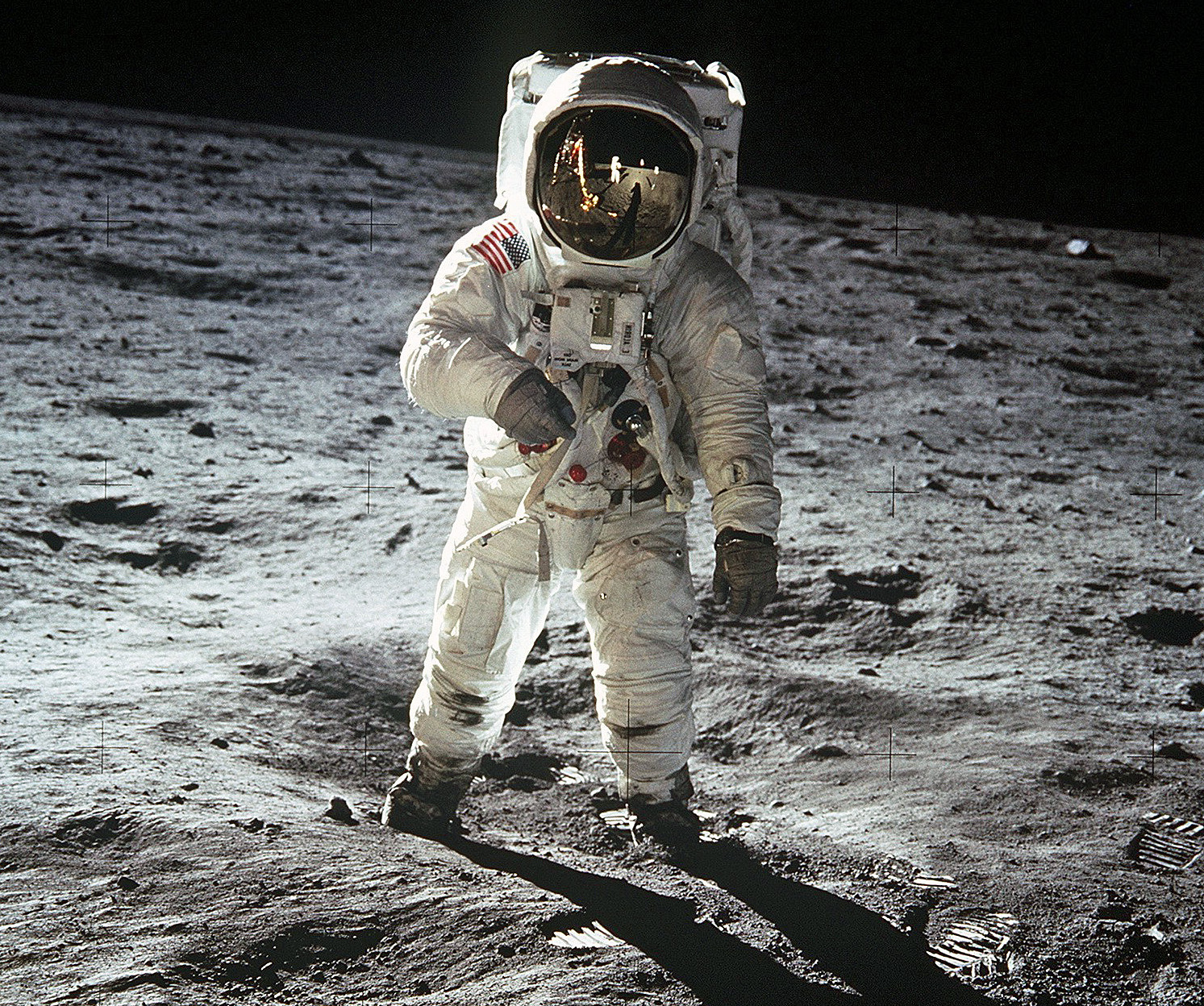

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin sat inside the Lunar Module Eagle as it touched down in the Sea of Tranquility at 20:17 UTC. For the folks at Mission Control in Houston, it was 3:17 PM on a Sunday. For people in Europe, it was already late at night or the early hours of Monday morning. This isn't just a trivia point. It’s a reminder that this was the first truly global media event, occurring simultaneously across a fractured, time-zone-divided world.

The descent that almost ended in a crash

Getting to the moon is one thing. Landing is a whole different beast. Honestly, the landing was terrifying.

While the world waited for the date Apollo 11 landed on moon to be etched into history books, the computer inside the Eagle was screaming at the astronauts. It was throwing "1202" and "1201" program alarms. Basically, the computer was overwhelmed. It was trying to do too many things at once. Steve Bales, the guidance officer in Houston, had to make a split-second call. He realized the computer was just cycling through tasks and wasn't actually failing. He gave the "Go."

But then there was the boulder field.

Armstrong looked out the window and realized the automated landing system was dropping them straight into a massive crater filled with car-sized rocks. He took manual control. He hovered. He tilted the lander forward to "stretch" the landing and find a clear spot.

Back in Houston, the fuel gauges were dropping. 60 seconds of fuel left. Then 30. The room was silent.

When the contact light finally flickered on, they had mere seconds of fuel remaining before they would have been forced to abort—or worse. "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Charlie Duke, the CAPCOM in Houston, famously replied that the guys on the ground were about to turn blue. He wasn't exaggerating.

📖 Related: Apple Watch User Guide Series 10: How to Actually Use the New Features

Why July 20, 1969, was a logistical nightmare

We think of the moon landing as a clean, heroic moment. In reality, it was a mess of schedules and human exhaustion.

The original plan didn't have them stepping out onto the surface immediately. They were supposed to sleep first. Can you imagine? You just landed on the moon and someone tells you to take a four-hour nap. Armstrong and Aldrin weren't having it. They requested to skip the rest period and go straight to the EVA (Extravehicular Activity).

It took hours to depressurize the cabin. Every second felt like an eternity for the millions watching back home. When Armstrong finally squeezed through the hatch and climbed down the ladder, it was 10:56 PM EDT.

- The Moon: High noon.

- Houston: Late evening Sunday.

- London: 3:56 AM Monday.

- Sydney: 12:56 PM Monday.

Because of this, newspapers around the world carry different dates for the most important event of the 20th century. If you collect old newspapers, you'll see "The Moon" in giant bold letters across Sunday editions in the US and Monday editions in the UK.

The technology that actually made it happen

We often hear that a modern toaster has more computing power than the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC). That’s actually true.

The AGC had about 32,768 bits of RAM. Your smartphone likely has 8 gigabytes or more. That is a difference of millions. But the AGC was a marvel because it was "hard-wired." Literally. The software was woven into "rope memory" by women in factories who threaded wires through magnetic cores. If you missed a single stitch, the mission failed.

Margaret Hamilton, who led the software engineering team at MIT, developed the priority scheduling that saved the landing during those 1202 alarms. She designed the system to realize that landing the ship was more important than the peripheral data tasks it was trying to run. Without her code, the date Apollo 11 landed on moon might have been a date of tragedy instead of triumph.

Dissecting the "Moon Landing was Fake" nonsense

It's impossible to talk about the date without addressing the skeptics. You've heard them. "Why are there no stars?" "Why is the flag waving?"

The stars aren't visible because the moon's surface is incredibly bright. It’s like taking a photo on a snowy day; the camera adjusts for the bright ground, making the dark background look pitch black. As for the flag? It had a horizontal rod to keep it extended because NASA knew there was no wind. The "waving" was just the fabric vibrating after the astronauts shoved the pole into the lunar regolith.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence against a hoax is the fact that the Soviet Union didn't call us out. We were in the middle of a Cold War. If the US had faked it, the USSR would have shouted it from the rooftops. They had the tracking capabilities. They knew exactly where those signals were coming from. They stayed silent because it was real.

The legacy of Tranquility Base

What happened after the date Apollo 11 landed on moon is just as fascinating as the landing itself. Armstrong and Aldrin spent about two hours and fifteen minutes outside the lander. They collected 47.5 pounds of moon rocks. They set up a seismometer to measure "moonquakes" and a laser ranging retroreflector that scientists still use today to measure the exact distance between the Earth and the Moon.

They also left behind a plaque. It says: "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind."

Note that the plaque doesn't specify the exact day. It just says July 1969. Even NASA knew the date was a matter of perspective depending on where your feet were planted on Earth.

What most people forget about the return

The landing was only half the battle. They had to get back. The ascent engine—the one that would lift the top half of the Eagle off the moon—had no backup. If it didn't fire, Armstrong and Aldrin were stranded. Forever.

President Richard Nixon even had a speech prepared in case they died. It’s a chilling read. It begins, "Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace."

Fortunately, the engine fired. They docked with Michael Collins in the Command Module Columbia. Collins is often called the "loneliest man in history" because while his partners were walking on the moon, he was orbiting the far side in total radio silence. He never got to walk on the surface, but without him, no one was going home.

Actionable steps for space history enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the reality of the Apollo missions, don't just rely on textbooks. There are ways to touch this history yourself.

- Visit the Smithsonian: The National Air and Space Museum in D.C. houses the actual Columbia command module. Seeing it in person—the scorch marks, the cramped quarters—changes your perspective on how brave those three men were.

- Read the Transcripts: NASA has the full mission transcripts available online. Reading the "raw" conversation between the astronauts and Houston provides a level of tension that no movie can replicate. Look specifically for the "Descent" phase.

- Track the LRO Photos: The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has taken high-resolution photos of the Apollo 11 landing site from orbit. You can actually see the descent stage of the Eagle and the footpaths made by the astronauts. It’s the ultimate "receipt" for the mission.

- Check the "Real-Time" Archives: Websites like Apollo in Real Time allow you to listen to the mission audio and watch the footage exactly as it happened, synced to the second.

The date Apollo 11 landed on moon represents more than just a box on a calendar. It was the moment humanity stopped being a single-planet species. Whether you celebrate it on July 20 or July 21, the achievement remains the high-water mark of human engineering and courage.