You’re driving through the high desert of Socorro County, New Mexico, and the landscape is doing that thing where it looks like a flat, dusty painting for miles. Then you hit Magdalena. You bank a left, head south for about three miles, and suddenly the ghosts start talking.

Actually, it’s mostly just the wind whistling through a 121-foot steel skeleton.

That tower is the Traylor shaft headframe, the undisputed king of the Kelly Mine New Mexico. It's not just some rusty relic. It was designed by Alexander Gustave Eiffel. Yeah, that Eiffel. The Tower-in-Paris guy. It was shipped in a kit from New Jersey back in 1906, which is basically the turn-of-the-century equivalent of an IKEA build, only with way more rivets and zero Swedish meatballs.

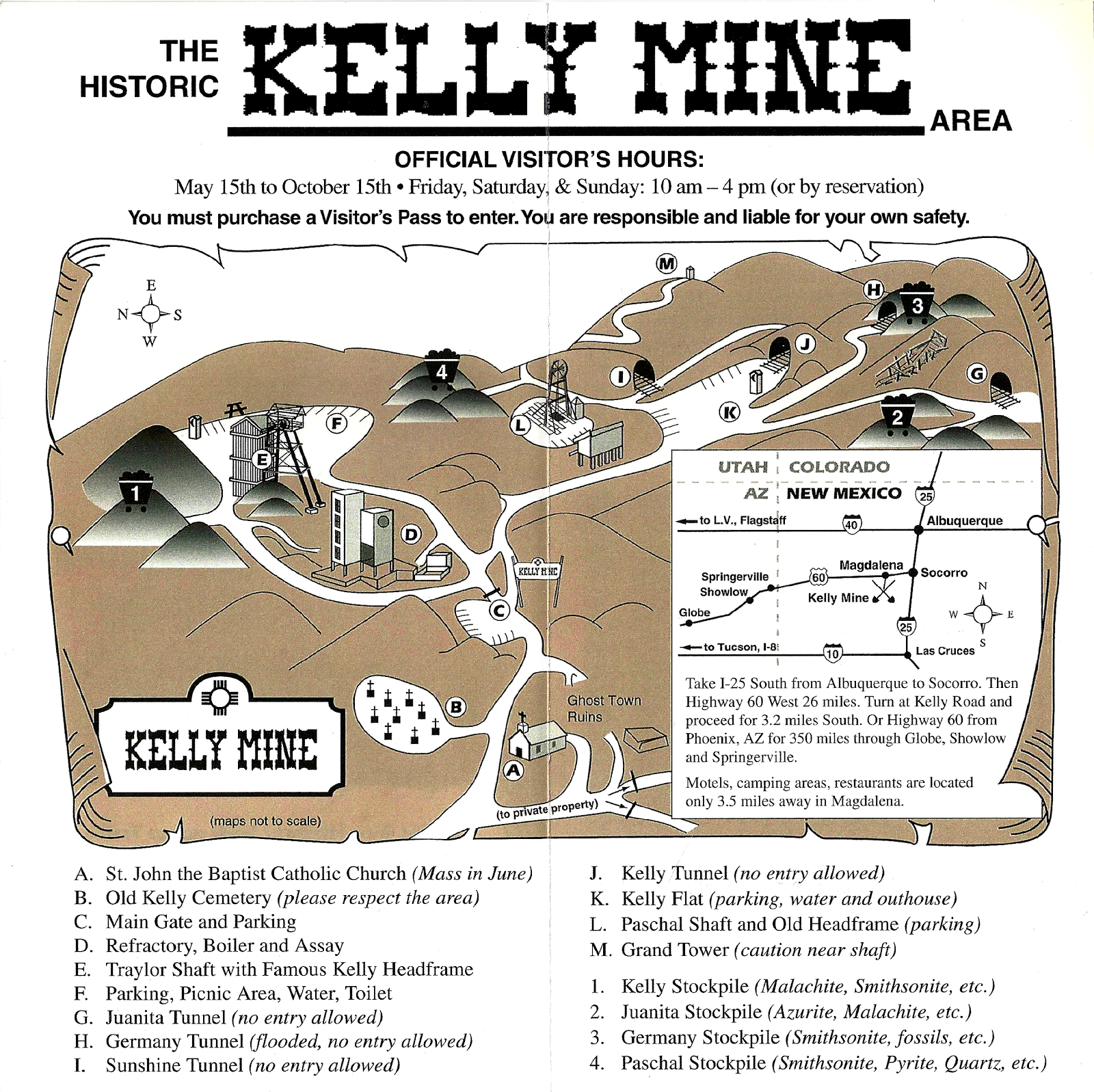

Most people come here for the "ghost town" vibes. They want to see the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church—which still holds a fiesta every June, by the way—or poke around the foundations of a town that once housed 3,000 souls. But the real story? It’s buried about 1,000 feet down in a 30-mile maze of tunnels that most folks will never see.

Why the Kelly Mine New Mexico Still Matters to Rockhounds

If you're into minerals, you know the name. If you aren't, you've probably seen the pictures: that weirdly beautiful, bubbly, blue-green stone that looks like it belongs on a tropical reef instead of inside a dusty mountain.

That's smithsonite.

For decades, miners at the Kelly Mine were actually annoyed by it. They were chasing lead and silver. They called the smithsonite "dry bone" or "gristle." They literally threw it onto the waste piles because it wasn't the "real" money.

The Cony T. Brown Turning Point

Honestly, the whole fate of the Kelly Mine changed because of a guy named Cony T. Brown. In the 1890s, he got curious about those discarded green rocks. He sent some samples to a smelter in Missouri, and the results were a "holy crap" moment. It wasn't trash; it was high-grade zinc carbonate.

Suddenly, the "useless" waste piles were worth a fortune.

The Kelly Mine became the premier source for what is now called "jeweler's grade" smithsonite. We aren't just talking about industrial zinc for paint. We're talking about botryoidal (grape-like) clusters with a luster that looks almost silky. To this day, if you find a piece of Kelly smithsonite in a shop, expect to pay hundreds—or thousands—of dollars.

💡 You might also like: Images of Royal Caribbean Ships: What You’re Actually Seeing vs. Reality

I’ve seen specimens from the old C.T. Brown collection that make modern lab-grown crystals look like driveway gravel. There is just something about that specific teal-blue hue that hasn't been matched anywhere else on Earth.

What it's like on the ground right now

If you go there today, don't expect a gift shop. This isn't Disneyland.

The Kelly Mine is private property, though the owners have historically been pretty cool about people wandering around the public-facing ruins as long as you aren't a jerk. You’ll see the Tri-Bullion smelter remnants—that tall brick chimney standing like a lonely cigarette—and the massive ore bins.

Pro tip: Wear boots. Real boots. The ground is a mix of sharp tailings, cactus, and "wait-a-minute" bushes that will shred your shins.

People still "surface mine" the tailings. You’ll see them with little rock hammers, hunched over like they lost a contact lens. You can still find bits of azurite, malachite, and if you’re lucky, a tiny "rice-grain" smithsonite crystal. But the big, museum-quality slabs? Those days are mostly gone unless you've got a time machine or a very deep wallet.

The dark side of the boom

It wasn't all pretty rocks and Eiffel towers. Kelly was a rough place. In 1883, there was a nasty bout of mob violence in what they called "Middle Camp." A mine superintendent tried to bring in a Chinese assistant, and the local miners—terrified of job competition—went full riot.

💡 You might also like: Rivers in Los Angeles: Why We Paved Them and Where to Find the Water Now

It’s a reminder that these "quaint" ruins were built on a lot of sweat, some blood, and a decent amount of old-school prejudice.

By 1931, the party was mostly over. The "pay ore" was gone. The Great Depression hit, and people literally started dismantling the houses in Kelly to move them down to Magdalena. They'd jack up a whole house, put it on a truck, and drive it three miles north. Most of the old houses you see in Magdalena today actually started their lives up at the mine.

How to visit without getting arrested (or lost)

First, check the weather. You're at the base of the Magdalena Mountains. It gets cold. It gets windy. And when it rains, those dirt roads turn into New Mexico "caliche" mud, which has the consistency of wet peanut butter and the sticking power of industrial epoxy.

- Location: 3.5 miles south of Magdalena, NM. Follow the signs for the "Kelly Ghost Town."

- Access: High-clearance vehicle is better, but a brave sedan can usually make it if the road hasn't been washed out recently.

- Safety: Stay out of the fenced-off shafts. Seriously. There are 30 miles of tunnels down there, many of them oxygen-depleted or ready to collapse. The Traylor shaft is 1,100 feet deep. That's a long way to fall for a cool Instagram photo.

One thing that's actually pretty cool is the "Kelly Mine Camp" run by New Mexico Tech. They use the area to help incoming freshmen bond. It’s a weirdly poetic circle—the place that built the economy of Socorro County 140 years ago is now helping build the next generation of engineers and geologists.

Is there still treasure there?

Depends on how you define treasure. If you're looking to get rich, no. The Empire Zinc Company and Tri-Bullion picked those bones clean decades ago.

But if you’re looking for a specific kind of silence? The kind you only find in a place where 3,000 people once lived and now zero do? Then yeah, it’s a gold mine.

The mineralogy is still world-class, even if the "easy" stuff is gone. Researchers are still finding rare stuff like Aldridgeite (a cadmium-bearing sulfate) in the old workings. It’s a "type locality" for several minerals, meaning it’s the place where they were first identified. For a geologist, that’s like visiting the birthplace of a celebrity.

The Actionable Reality

If you’re planning a trip to the Kelly Mine New Mexico, don't just "show up."

Start at the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Museum in Socorro. It’s only 25 miles away. They have the "best of the best" Kelly specimens on display. Look at those first. Understand the "velvet" texture of the smithsonite. Then, drive up to the mine site.

Seeing the scale of the headframe against the backdrop of the mountains, knowing what those stones looked like when they came out of the dark—that’s the real experience.

Bring a camera with a good zoom. The way the light hits the Traylor headframe at sunset is basically the reason landscape photography was invented. Just remember: take only pictures, leave only footprints, and for the love of everything, don't climb on the ruins.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Real Picture of Elephant Bird: What Most People Get Wrong

They’ve stood for over a century; don't be the reason one of them finally tips over.

To make the most of your visit, head to the Magdalena Village office or the local library first. They often have maps or pamphlets that explain which foundations belong to which business. You’ll find that "Middle Camp" wasn't just a mine; it was a community with a bank, a clinic, and more saloons than you could shake a pickaxe at.

Once you’re on the site, stick to the main paths near the church and the headframe. If you want to find your own minerals, focus on the edges of the older waste piles further from the main road—weathering often exposes small "blue caps" of smithsonite after a heavy rain.