You’ve seen it a thousand times. That sleek, repeating "S" curve sitting in the middle of a physics quiz. Usually, it’s a bright blue line on a white background, cluttered with arrows pointing every which way. But a labelled diagram of a wave isn't just schoolwork filler; it is the literal blueprint for how your Wi-Fi reaches your phone, how your microwave thaws a frozen burrito, and how you're even hearing the world around you right now.

Waves are everywhere.

They are disturbances. That’s the simplest way to put it. When you drop a pebble into a pond, you aren't actually seeing water move from the center to the edge. You’re seeing energy move through the water. The water molecules just bob up and down, mostly staying put. This is the first thing people get wrong. They think the "stuff" moves with the wave. It doesn't. The energy does.

The Anatomy of a Transverse Wave

Let’s get into the guts of the thing. If you’re looking at a standard labelled diagram of a wave, you’re likely looking at a transverse wave. Think of a rope tied to a doorknob that you’re shaking up and down.

The highest point? That’s the crest. It’s the peak of the mountain. The lowest point is the trough. It’s the valley. These are the two extremes of displacement. If you draw a straight line right through the middle—where the rope would sit if you weren't shaking it—that’s your equilibrium or "rest position."

Now, the distance from that center line to the top of a crest is the amplitude. This is where things get interesting. In sound, amplitude is volume. In light, it’s brightness. If you’ve ever wondered why a loud concert feels like it’s physically hitting your chest, it’s because those waves have massive amplitude. They’re carrying a ton of energy.

Then there’s wavelength. You measure this from one crest to the very next crest. Or trough to trough. It doesn't really matter as long as you're measuring the distance between two identical points on consecutive cycles. In physics, we usually use the Greek letter lambda ($\lambda$) to represent this. It’s a distance, so we talk about it in meters, nanometers, or even kilometers if we’re talking about massive radio waves.

Frequency and the Time Element

You can't really talk about a labelled diagram of a wave without mentioning frequency, even though it’s harder to draw. Frequency is the "how often." If five waves pass a certain point in one second, you have a frequency of 5 Hertz (Hz).

There is a weird, inverse relationship here that messes people up. High frequency means short wavelength. Low frequency means long wavelength. Imagine a frantic toddler running—lots of little steps (high frequency, short wavelength). Then imagine a giant taking slow, massive strides (low frequency, long wavelength).

🔗 Read more: How to Change the Picture on Your Google Account Without Breaking Your Sync

What About the Waves You Can't See?

Most diagrams focus on the "up and down" stuff because it's easy to visualize. But sound doesn't work like that. Sound is a longitudinal wave. Instead of moving up and down, the particles move back and forth in the same direction the wave travels.

If you were to look at a labelled diagram of a wave for sound, you wouldn't see crests and troughs. You’d see compressions and rarefactions.

- Compression: This is where the air molecules are smashed together. It’s a high-pressure zone.

- Rarefaction: This is where they’re spread apart. A low-pressure zone.

Honestly, it looks like a slinky being pushed and pulled. The "wavelength" here is the distance between two compressions. Even though it looks different, the math is the same. The physics doesn't change just because the visual does.

The Speed Myth

Here is a nuanced point that often gets skipped. The speed of a wave ($v$) is determined by the medium it’s traveling through, not by how hard you shake the rope. If you yell louder, the sound doesn't get to your friend faster. It just gets there louder.

The formula $v = f \lambda$ (velocity equals frequency times wavelength) is the holy grail here. If the speed is constant—like light traveling through a vacuum—then if the frequency goes up, the wavelength must go down. This is why gamma rays have tiny wavelengths while radio waves can be the size of buildings. They’re all part of the same electromagnetic spectrum; they just have different "labels" on their diagrams.

Real-World Nuance: Phase and Interference

If you want to move beyond the basic classroom stuff, you have to look at phase.

Phase describes where a wave is in its cycle at a specific time. If two waves are "in phase," their crests line up perfectly. When they hit each other, they add up. This is constructive interference. It’s how "noise-boosting" speakers work.

But if they are "out of phase"—meaning one's crest hits at the exact same time as the other's trough—they cancel each other out. This is the magic behind those high-end noise-canceling headphones. They literally create a "negative" wave of the background noise, flatlining the amplitude so you hear nothing but your music.

Why the Diagram Matters for Tech

Engineers spend their lives staring at these diagrams. In fiber optics, the wavelength of light determines how much data we can shove through a cable. In medicine, ultrasound machines use the reflection of high-frequency waves (tiny wavelengths) to "see" inside the body. If the wavelength was too big, it would just pass right through without reflecting off the small details of an organ or a fetus.

We use these labels to categorize the universe. Without the distinction between amplitude and frequency, we couldn't tune a radio, perform LASIK surgery, or predict when a tsunami is going to hit a coastline.

Actionable Insights for Mastering Wave Physics

If you're trying to memorize a labelled diagram of a wave for an exam or just to understand the tech in your pocket, stop trying to memorize the picture. Understand the relationship.

🔗 Read more: Why Your Cell Animal Project 3D Is Failing (And How to Fix It)

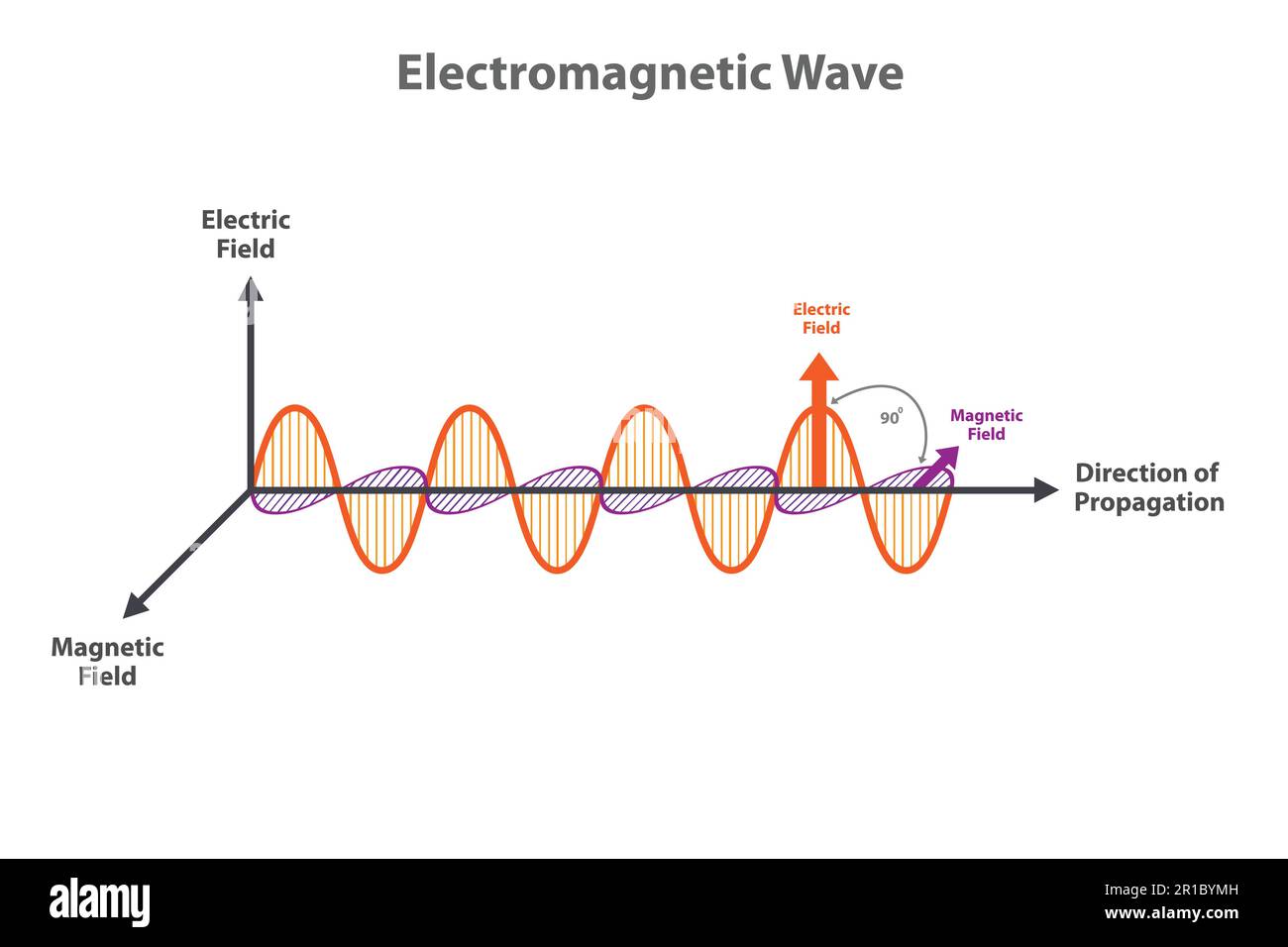

- Visualize the Medium: Always ask, "What is actually moving?" If it's a water wave, it's water. If it's a light wave, it's oscillating electric and magnetic fields.

- The Energy Rule: Remember that amplitude equals energy. If you want more power, you need more amplitude. If you want more "data" or different "colors," you change the frequency/wavelength.

- Draw it Yourself: Don't just look at a diagram. Draw a baseline. Draw a wave. Label the equilibrium first. Everything else—crest, trough, amplitude—is measured relative to that line.

- Check the Units: If you're looking at a diagram in a textbook, check the axes. Is the horizontal axis "Distance" or "Time"? If it's distance, you're looking at wavelength. If it's time, you're looking at the period (the time it takes for one full cycle to pass). This is a classic trap in physics problems.

Waves are the heartbeat of the physical world. From the seismic rumbles of the Earth's crust to the invisible signals bouncing off satellites, the geometry stays the same. Once you can label one, you can understand them all.