Space is mostly empty. You've heard that since grade school, right? But here’s the thing: it’s not just empty; it’s messy. Gravity from the Sun, the Earth, and the Moon is constantly pulling at everything in a chaotic tug-of-war. If you want to keep a satellite in one place without burning through a mountain of fuel, you’re basically fighting the physics of the entire solar system. Except, sometimes, you don't have to. There are these weird, invisible "sweet spots" where the gravity of two large bodies—like the Earth and the Sun—cancels out the centrifugal force felt by a smaller object. We call this a Lagrangian point.

Think of it like a marble on a hilly landscape. Most of space is a steep slope where the marble just rolls away. But a Lagrangian point is like a little dip or a very precise ridge where the marble can just... sit there.

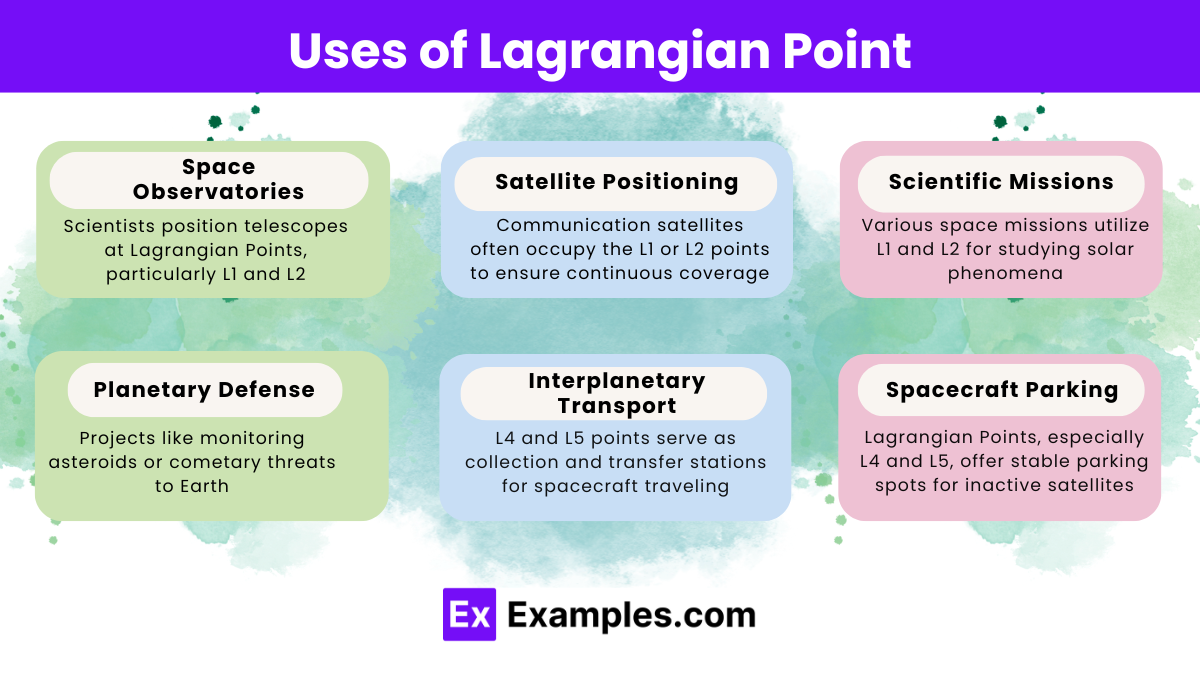

Joseph-Louis Lagrange, an 18th-century mathematician who probably had way too much time on his hands, figured this out back in 1772. He realized that in any two-body system, there are exactly five of these points. They aren't physical objects. You can't crash into a "Lagrange" because there's nothing there but a gravitational equilibrium. Yet, these empty spots are the most valuable real estate in our neck of the woods. Without them, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) would be a multibillion-dollar piece of floating junk, and we’d have a much harder time spotting "planet-killer" asteroids before they got too close.

The Five Points: Not All Spots Are Created Equal

The math gets heavy fast, but the concept is actually pretty intuitive if you stop thinking about space as a flat map. Every two-body system—Sun-Earth, Earth-Moon, Sun-Jupiter—has five specific points.

💡 You might also like: Energy is never created nor destroyed: Why the First Law of Thermodynamics changes how you see the world

L1: The Sun-Watcher

The first point, L1, sits directly between the two large masses. If you’re looking at the Sun-Earth system, L1 is about 1.5 million kilometers away from us, heading straight toward the Sun. It’s the perfect spot for the SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) satellite. Why? Because from L1, you have an uninterrupted view of the Sun 24/7. No pesky Earth getting in the way or blocking your view with its pesky atmosphere.

L2: The Dark Side

Then there’s L2. This is the big one right now. It’s located on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun. It stays in Earth’s shadow, sort of. Actually, it’s a bit further out than the shadow, but it allows a telescope like the JWST to keep the Sun, Earth, and Moon all behind it. This is crucial. If you’re trying to see the faint heat signatures of galaxies from the beginning of time, you can’t have the Sun’s massive heat signature blinding your sensors. L2 is essentially the ultimate "do not disturb" sign for infrared astronomy.

L3: The Great Unknown

L3 is the weirdest one. It’s hidden behind the Sun, exactly opposite the Earth’s orbit. If the Earth is at 12 o’clock, L3 is at 6 o'clock. We can’t see it from Earth. In old sci-fi novels, people used to write about a "Counter-Earth" hiding there. Spoilers: there isn't one. It’s pretty much useless for us right now because it’s so far away and communication would be a nightmare since the Sun blocks all our signals.

L4 and L5: The Gravity Traps

These are the "stable" points. While L1, L2, and L3 are like balancing a needle on its tip (you need a little fuel to stay there), L4 and L5 are like bowls. If something drifts into L4 or L5, it tends to stay there. These points sit 60 degrees ahead of and 60 degrees behind the smaller body in its orbit. Jupiter’s L4 and L5 points are famously crowded with "Trojan asteroids." There are thousands of them. Earth has a few too, though they’re much harder to find.

Why a Lagrangian Point Isn't Just a "Point"

Okay, honestly, calling it a "point" is a bit of a lie. In reality, satellites at L1 or L2 aren't just sitting still like a parked car on a street. That would be impossible because the equilibrium is unstable. If you nudge a satellite at L2 just a tiny bit, it wants to fall away toward the Sun or fly off into deep space.

Instead, spacecraft perform what we call "halo orbits" or "Lissajous orbits."

They actually orbit the empty space itself. It looks like they’re circling nothing. But by doing these weird, loopy dances, they can maintain their position relative to the Earth and Sun with minimal fuel consumption. The JWST, for instance, is constantly moving in a giant loop around the L2 point. This keeps it out of the Earth's shadow so its solar panels can still get power, while keeping its sensitive mirrors pointed into the dark cold of the outer system.

The Real-World Stakes of Gravitational Balance

We aren't just talking about abstract physics here. This is about survival and science.

👉 See also: Why Every Drone Shuts Down Airport Operations and the Gatwick Chaos That Changed Everything

Take the DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory) satellite at L1. It’s our early warning system. If the Sun decides to hurl a massive Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) at us—basically a billion-ton ball of magnetized plasma—DSCOVR sees it about 15 to 60 minutes before it hits Earth. That’s enough time to flip satellites into "safe mode" and protect power grids from blowing up. If we didn't have that "parking spot" at L1, we'd be flying blind.

Then there’s the future. NASA and other agencies are looking at the Earth-Moon L2 point as a site for a future fuel depot or a staging ground for Mars missions. Because gravity is so balanced there, it takes very little energy to leave that point and head elsewhere. It’s the ultimate freeway on-ramp for the solar system.

Common Misconceptions About These Spots

People often think Lagrangian points are like vacuum cleaners that suck things in. They aren't.

For L1, L2, and L3, you actually have to work to stay there. If your satellite runs out of fuel and stops doing its station-keeping maneuvers, it will eventually drift away. It doesn't just stay "parked" forever. This is why mission lifespans are so strictly tied to how much propellant is on board. Once the gas is gone, the "spot" is lost.

Another weird myth is that L4 and L5 are dangerous because they're full of rocks. While Jupiter's Trojans are a thing, Earth’s L4 and L5 are mostly empty. We’ve sent probes like OSIRIS-REx to peek at them, and it’s not the asteroid belt scene from Star Wars. It’s still mostly empty space—just space where things could stay if they happened to end up there.

Engineering the Impossible

Designing a mission for a Lagrangian point is a nightmare for engineers. You have to account for solar radiation pressure—the literally tiny "push" from sunlight hitting the spacecraft. Over months and years, that tiny push is enough to knock you out of your orbit around the point.

The math involved looks something like this (for the nerds):

$$F_g = G \frac{M_1 m}{r^2}$$

But you aren't just dealing with one $F_g$. You're dealing with the sum of gravitational forces from two moving bodies while accounting for the centrifugal force of your own orbital motion. When all those vectors add up to zero, you've found your spot.

It’s a delicate balance.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts and Professionals

If you’re tracking the next generation of space missions, or just want to understand the night sky better, keep these things in mind:

- Watch the L2 Mission Queue: With JWST already there, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Euclid mission and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope are all heading to the same neighborhood. It's getting crowded.

- Follow Solar Weather: Check the data from L1-based satellites like SOHO or DSCOVR. They provide the "weather reports" for our planet's electronic infrastructure.

- Keep an eye on the Moon: As we move toward a permanent lunar presence (Artemis missions), the Earth-Moon L1 and L2 points will become the most talked-about locations in news cycles. They are the gateways to the lunar surface.

- Understand the fuel limits: When you hear a mission "has 10 years of fuel," remember that much of that fuel isn't for traveling—it's just for the constant, tiny adjustments needed to stay balanced at a Lagrangian point.

The next time you look at a photo of a galaxy billions of light-years away, remember that the camera was sitting in a "hole" in gravity, 1.5 million kilometers away, perfectly balanced on a mathematical tightrope. It's one of the few places where the universe actually gives us a break and lets us sit still for a while.